Turkey believes that its relationship with Syria, and the credit it has accumulated with President Assad, may permit it to convince him to respond to the legitimate demands of his people, either through advice or through pressure, in a manner capable of ending the domestic crisis and sparing the Syrian state, as well as Turkey, a great debacle with events deteriorating further, especially considering Turkey is willing to provide the needed support for the enactment of radical reforms in Syria.

The Turkish position towards the Syrian crisis is advancing slowly, but with an escalating rate of pressure over Assad. Ankara has legitimate concerns and is relying - at the same time - on a number of objective variables to draw its position regarding the crisis in Syria. The Turkish calculations are extremely complex, with Turkey attempting to balance sensitive considerations while creating and solidifying its stance.

Turkey is aware that "change" will sweep the region as a whole, but is concerned of a scenario of disastrous chaos due to the Syrian regime's links to explosive files Turkey hopes to manage this issue in a manner that preserves the popular rights and demands that it supports, while, at the same time, sparing it disastrous consequences if things slide into chaos.

Time will be the main factor in this equation; if Assad succeeds in crushing the protests by emulating the Iranian option in dealing with dissent, he would impose a fait accompli on everyone, which would place Turkey in a very embarrassing position vis-à-vis Syria, which would also apply to the international community. However, if Assad turns a deaf ear to the Turkish advice, while failing to suppress the protests, he would be placed under even greater pressures, and the Turkish position would likely fall in line with those pressures.

The special relationship between Turkey and Syria is one of the main foreign achievements of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) since its assumption of power in 2002. After the two countries were on the brink of war in 1998, relations between them evolved following the Adana Accord, which was signed on October 20, 1998, effectively ending Syria's hosting of the Kurdistan Workers' Party. The AKP's assumption of power in Turkey in 2002 permitted further rapprochement with Syria; President Assad visited Turkey in 2004, and the Turkish President, Ahmet Necdet Sezer, responded with a visit to Syria in 2005[1] despite the strong protests from the Bush administration, which was tightening the political and diplomatic isolation and siege over Syria.

The Turkish foreign policy saw a major and quick transformation when Abdullah Gul[2] and Recep Tayyip Erdogan[3] prepared for the adoption of the vision of Ahmet Davutoglu,[4] who was an advisor to Erdogan at the time, aiming at redefining Turkey's role in the region within the concept of "strategic depth," a phrase coined by Davutoglu.[5]

Since the adoption of the "zero conflict" policy emanating from Davutoglu's vision, a reversal took place in a number of traditional policies of the Turkish Republic, especially in relation to foreign policy;[6] thus, relations between Turkey and Syria developed into a strategic relationship, effectively resolving many of the standing issues between the two countries; this relationship took an even more significant turn with Davutoglu's assuming the helm of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2009.

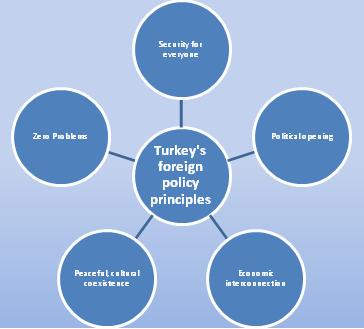

Turkey's Foreign Policy in the Middle East[7]

Graph 1: Turkey's foreign policy principles (designed by the author)

In 2009, a strategic cooperation council was founded, which is headed by the head of the governments of Syria or Turkey, depending on the place of the council's meeting. The council includes 16 ministers from both countries (foreign affairs, interior, defense, energy, transport, agriculture, and public works; other ministries - such as tourism - could also be included when needed). Two sessions are held annually (one in each country), with the aim of accomplishing the goals of the strategic relations between the two countries.[8]

Furthermore, in 2009, the first common military exercises between the two countries were held,[9] and entry visas were abolished in an initiative exhibiting the depth of relations between the two countries.[10] The total number of agreements signed between the Syrian regime and Turkey in the first session of the cooperation council reached 56 accords in a multitude of fields: politics, economics, society, culture, investment, water, banking, and others.[11] All of these agreements were also enacted precisely according to schedule, which is noteworthy from the viewpoint of the commitment of the two parties and the seriousness of the relationship between them. Moreover, commercial trade between the two countries increased from $730 Million in 2000 to over $2.3 Billion in 2010 (with both sides anticipating - before the Syrian crisis - that annual trade would reach $5 Billion within a short span of time).[12]

In 2010, an agreement was signed based on a Turkish proposal to create a common trade zone that would include Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon, with the possibility remaining open for other countries to join; visas would be abolished between the member states and harmonized regulations will be put in place in order to spur economic, commercial, and investment cooperation - a structure that resembles an embryonic Middle Eastern Union.[13]

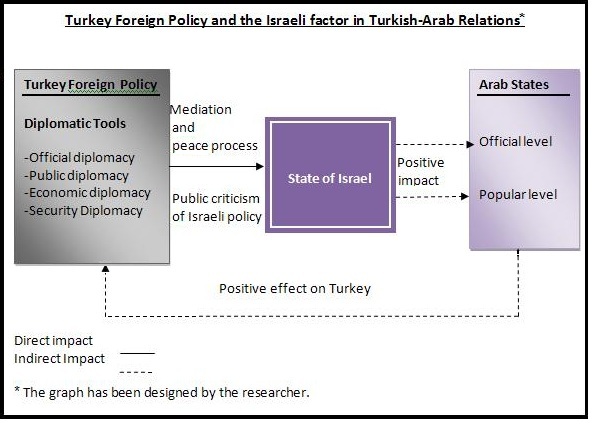

During this period, Syria acquired a critical level of importance for the new Turkish foreign policy of the Justice and Development Party, which helped in fomenting the Turkish strategic vision for the Middle East and the nature of its role within it.[14] As a result, Turkey was present in many of the heated and explosive files involving Damascus, ranging from Lebanon to Palestine to Israel to Iraq. Furthermore, the spread of the Turkish "soft power"[15] had a major effect on the ascension of Turkey's stature and role in the region and the development of its relations not only with Arab regimes, but - foremost - with their peoples, especially with the support of public diplomacy and numerous statements critiquing the Israeli position (see figure below).[16]

Figure 2: the Israeli factor in Turkish-Arab relations

On the Syrian side, rapprochement with Turkey came at a very opportune moment: the regime saw its relations with ascending Turkey as an outlet to escape the international siege that it had been lying under (a policy led by the United States and the Bush administration, especially after the 2003 Iraq invasion, the assassination of Hariri in 2005, the July aggression against Lebanon in 2006, and the aggression against Gaza in 2009). Relations with Turkey also constituted a bridge for Syria to reconnect with the European countries and the international community.[17] Even more importantly, close ties with Turkey offered Syria an alternative course that dissipates the imagery of the minoritarian "Alawi" sectarian rule that is allied with "Shia Iran" in the heart of the Arab world. This permits Syria to escape the policy of Iranian monopoly as Tehran was being pressured over its nuclear program and its negative role in the Arab region.[18]

In the midst of these events, relations evolved even on the interpersonal level, with a personal - and even familial - friendship forming between Bashar al-Assad and the First Lady, and several Turkish figures, especially Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who used to visit Damascus frequently, while Assad and his wife have spent a number of vacations in Turkey. Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, on the other hand, admits that "in eight years, I have visited Syria over sixty times, while I visited my own hometown in Turkey only twenty times!"[19]

With the flaring of Arab revolts throughout the beginning of 2011, the Syrian regime stressed the "exceptionality" of its situation and condition based on the premise that the "rejectionist card" would grant immunity to the regime and that it would be sufficient to provide it with the necessary popular cover in the Syrian domestic arena. In fact, the regime seemed confident that no protests would take place in the Syrian interior; in a Wall Street Journal interview on January 31, 2011, President Bashar Al-Assad said: "the situation cannot be compared to Egypt. If you wish to do so, then you need to look from a different angle ... Syria is stable, why? ... because we are close to the people and are intimately tied to the citizens' beliefs ... Despite the fact that out situation is difficult because of the sanctions, and despite the fact that people are lacking a lot of basic necessities, you do not see them coming out in protest."[20]

The middle of March saw the eruption of the popular uprising against the regime, and the situation of the Syrian leadership remained critical because of the escalation of internal protests in the face of the authorities' refusal to respond to popular demands, even though Turkey advised them to execute reforms over a year ago.[21]

The Syrian popular upheaval placed the Turkish government in an equally difficult position due to the specificity of the relationship with Syria on the one hand, and its anticipated position towards the events in Syria from the Syrian regime and the Syrian people. This took place in a context where viewpoints were divided between those expressing suspicions vis-à-vis the Turkish role, accusing it of supporting the regime, while others were accusing it of duplicity - compared to their positions on the revolutions in Egypt and Libya - as well as those despairing since they believe that Turkey is not in possession of the necessary tools to garner significant effect.[22]

This research paper aims at studying the elements determining the Turkish position towards the Syrian crisis, especially in the period ranging from the start of the protests in mid-March 2011 to the beginning of June; the study will examine the interconnected circumstances and factors that led to the cementing of that position. We shall conduct this research from the "Turkish lens," looking into the dimensions of the Turkish positions and the repercussions that they will have over the relationship between the two countries during this crisis and the phase that will follow.

The methodology employed in this study relies on a combination between the tools of the descriptive and deductive methodology, as well as those of the analytic and interpretive method. Additionally, it relies on close, daily monitoring of Turkish sources and the positions of Turkish officials during the period covered in this study.

The import of this paper lies in its attempt to determine the premises of the Turkish position during the crisis with the aim of employing them to assess the prospective position towards the Syrian crisis in the event that the circumstances change, and the position that Turkey would occupy in such scenarios, either with Assad responding to popular demands and enacting deep reforms that would satisfy the public, or with the Syrian president ignoring these demands and persisting with his reliance on the repressive security/military policy in order to crush the protests.

---------------------------------

- [1] See: Turkey´s Political Relations with Syria, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Turkey: www.mfa.gov.tr/turkey_s-political-relations-with-syria.en.mfa.

- [2] Abdullah Gul was the prime minister between 2002 and 2003, foreign minister between 2003 and 2007, and President of the Republic since 2007.

- [3] Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been Turkey's prime minister since 2003.

- [4] Ahmet Davutoglu has been the minister of foreign affairs since 2009.

- [5] For more details on this transformation and Turkey's project for the region, see Ali Husain Bakeer's article, published by the General Directorate for Media and Information in the Office of the Turkish Prime Minister on April 7th, 2010, available in Turkish and Arabic from http://alibakeer.maktoobblog.com/1599534.

-

[6] Ali Husain Bakeer, "The New Turkey - regional ascendance and the conflict of agendas",

Madarat Istratijiya (magazine), Sabaa Center for Strategic Studies in Yemen, Year 1, Issue 1, November-December 2009, pp. 110-114 (in Arabic), available at, http://alibakeer.maktoobblog.com/1599445

.

- [7] For details more information on the diagram, see Ahmet Davutoglu, "Turkey's Zero-Problems Foreign Policy", Foreign Policy Magazine, May 2010, www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2010/05/20/

turkeys_zero_problems_foreign_policy.

- [8] For further information on the strategic cooperation council, see Veysel Ayhan, "Turkey-Syria High Level Strategic Cooperation Council Period", ORSAM, December 8, 2009: www.orsam.org.tr/en/showArticle.aspx?ID=107

- [9] See Bilal Y. Saab,"Syria and Turkey Deepen Bilateral Relations", Saban Center for Middle East Policy, Brookings, May 6, 2011: www.brookings.edu/articles/2009/0506_syria_turkey_saab.aspx.

- [10] See Emine Kart, "Ongoing crisis justifies Turkey's policy of engagement with Syria", Today's Zaman, May 1, 2011, www.todayszaman.com/news-242446-ongoing-crisis-justifies-turkeys-policy-of-engagement-with-syria.html.

- [11] For further details on the first meeting of the strategic council, see: Veysel Ayhan, "Turkish-Syrian Strategic Cooperation Council's First Prime Ministers Meeting", ORSAM, December 30, 2009, www.orsam.org.tr/en/showArticle.aspx?ID=125.

- [12] For more details on commercial and economic relations between the two countries, see: Turkey-Syria Economic and Trade Relations, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Turkey, www.mfa.gov.tr/turkey_s-commercial-and-economic-relations-with-syria.en.mfa.

- [13] Piotr Zalewski, "Why Syria and Turkey Are Suddenly Far Apart on Arab Spring Protests", Time, May 26, 2011, www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2074165,00.html.

- [14] For a more expansive discussion of Turkey's foreign policy vision and the nature of its role in the region, see Ali Husain Bakeer, "The determinants of the new Turkish foreign policy - the introduction to understanding the Turkish role in the region," Ara' Hawl al-Khaleej Journal, al-Khaleej lil Abhath, UAE, Issue 71, August 2010, pp. 69-72(in Arabic).

- [15] For a further discussion of Turkish "soft power," see: Ali Husain Bakeer, "Turkish soft power in the balance of Arab transformations", Islam Online, March 18, 2011 (in Arabic), http://alibakeer.maktoobblog.com/1599989.

- [16] The figure was prepared by the author and is quoted from his unpublished research paper, which was presented at the Turkish-Arab Relations Conference, which was held in Kuwait on January 11, 2011. The paper is entitled, "The role of the media in the building of strategic Arab-Turkish relations" (in Arabic). A published summary of it can be read in: Ali Husain Bakeer, "The missing element in Arab-Turkish relations," Ara' Hawl al-Khaleej Journal, al-Khaleej Research Center, UAE, March 2011, http://alibakeer.maktoobblog.com/1599951.

- [17] İhsan Bal, "Can Assad's Regime Get off the Hook Again?," USAK, May 18, 2011, www.usak.org.tr/EN/haber.asp?id=754.

- [18] Ali Husain Bakeer, "Those who stand to lose from the ascending Turkish role" (In Arabic), Al-Nahar (Lebanese newspaper), June, 13, 2010 (in Arabic), http://alibakeer.maktoobblog.com/1599579.

- [19] "Turkey Calls for Syrian Reforms on Order of ‘Shock Therapy'," The New York Times, May 25, 2011, www.nytimes.com/2011/05/26/world/europe/26turkey.html.

- [20] Interview With Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, The Wall Street Journal, January 31, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article

/SB10001424052748703833204576114712441122894.html.

- [21] In a May 12, 2011 interview with Charlie Rose on the Bloomberg Channel, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan said that "Bashar is a good friend of mine"; he also revealed that "we discussed last year the lifting of the state of emergency and the release of political prisoners and issues such as the electoral system and the permitting of party pluralism ... I even agreed that he studies our experience in the Justice and Development Party and I told him frankly: if you find it necessary, send us your men, we could train them and show them the mode of operation in our Party so that they learn how to organize a political party and build links with the people and communicate with them."

- [22] See, for an illustration, Zain al-Shami, "Turkey's advice to the Syrian regime," Kuwaiti al-Rai newspaper (In Arabic), www.alraimedia.com/Alrai/Article.aspx?id=271220..