The 2017-2018 Arab Opinion Index is the sixth in a series of yearly public opinion surveys across the Arab world. The first survey was conducted in 2011, with following surveys in 2012/2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016.

The 2017-2018 Arab Opinion Index is based on the findings from face-to-face interviews conducted with 18,830 individual respondents in 11 separate Arab countries: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq, Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, Egypt, Sudan, Tunisia, Morocco and Mauritania. Sampling followed a randomized, stratified, multi-stage, self-weighted clustered approach, giving an overall margin of error between +/- 2 % and 3% for the individual country samples. The overall samples guarantee probability-proportional-to-size (PPS), ensuring fairness in the representation of various population segments. With an aggregate sample size of 18,830 respondents, the Arab Opinion Index remains the largest public opinion survey in the Arab world. The fieldwork was carried out by an overall team of 840 individuals, equally balanced on gender, who conducted 45,000 hours of face-to-face interviews. The team covered a total of 700,000 kilometers across the population clusters sampled.

The sections below give selected highlights of the findings of the 2016 Arab Opinion Index.

Section 1: Living Conditions of Arab Citizens

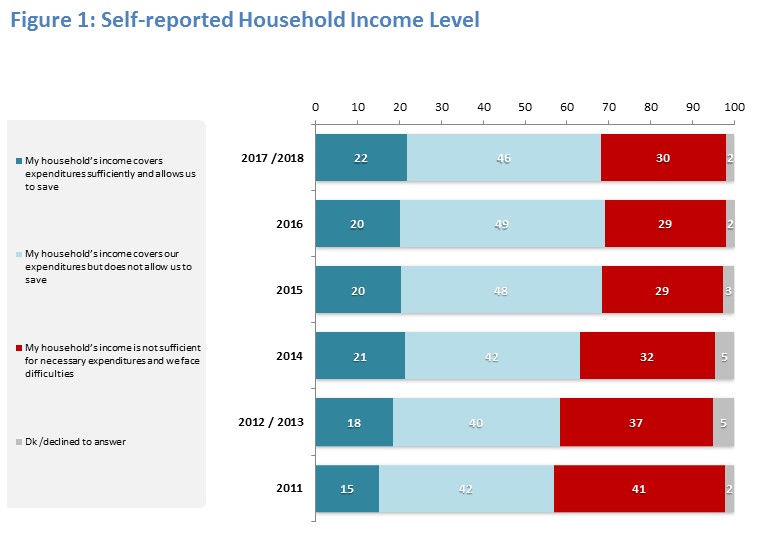

● Only 22% of respondents reported that their household income was sufficient for them to make savings after all of their necessary expenditures were covered. A further 46% reported that while their household incomes were sufficient to cover necessary expenditures, it was not enough to sustain savings. These families are designated as those living "in hardship." Fully 30% of citizens in the Arab region live "in need," in that their household incomes do not cover their necessary expenditures whatsoever. When comparing to the baseline year of 2011, households considered "in need" has reduced 11%, which is a significant difference.

● Of those respondents whose households live "in need", 55% resort to borrowing from a variety of sources, including family and friends as well as banks and financial institutions, to cover their expenditures. Another 17% rely on handouts and charitable assistance from friends and family, while 15% on assistance from charitable organizations.

● Of those respondents whose households live "in need", 55% resort to borrowing from a variety of sources, including family and friends as well as banks and financial institutions, to cover their expenditures. Another 17% rely on handouts and charitable assistance from friends and family, while 15% on assistance from charitable organizations.

● 64% of respondents evaluate the level of safety/security in their home countries positively, while 35% view the level of safety/security in their home countries negatively. This reflects an increasingly positive perception of the levels of safety and security throughout the region.

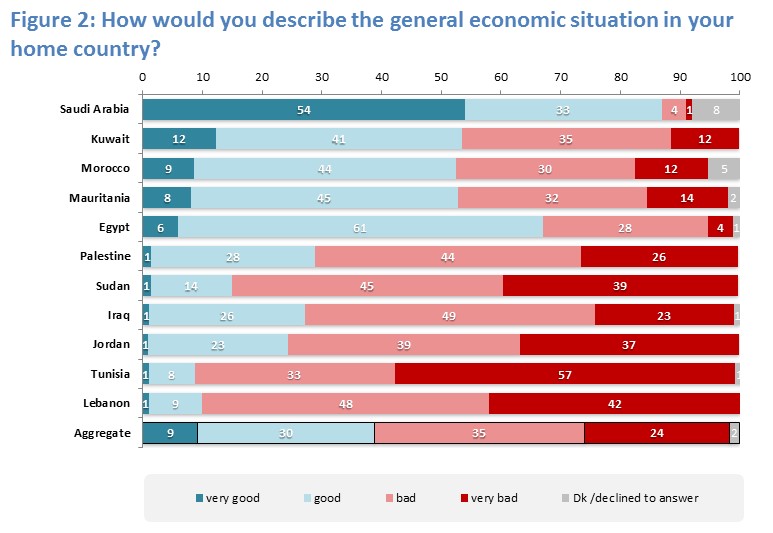

- 39% of respondents evaluate their home countries' economic situations positively, compared to 59% who have an overall negative view of their home countries' economic circumstances. This measure has remained stable across successive polls of the Arab Opinion Index.

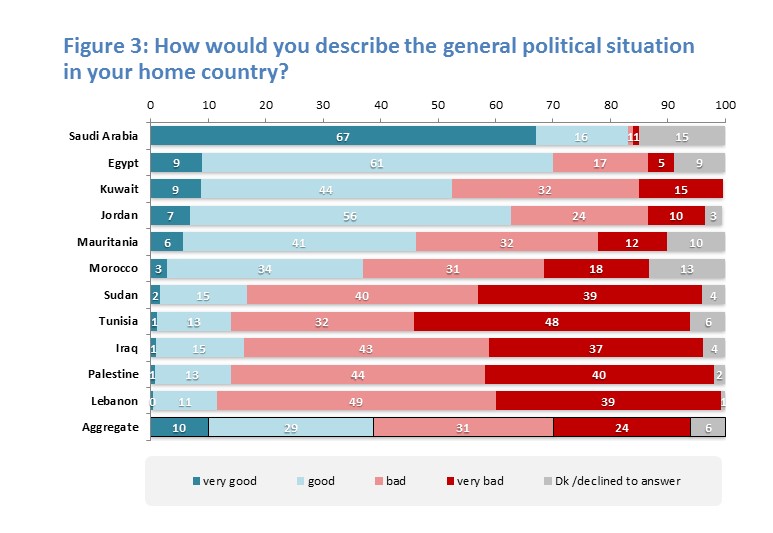

● Similarly, 39% of respondents evaluated the political situations within their home countries positively, compared to 55% who had negative views of their home countries' political situations. This represents a stalling of a previous improvement in Arab public perceptions of their home countries' political situations, which was especially notable during the 2015 survey.

● When asked to identify the most pressing problems for their countries to tackle, 33% of respondents provided answers which focused on economic issues: unemployment, poverty, and price inflation. A further 10% offered answers which centered on safety, security and stability while 22% gave answers which concerned political issues, such as governance, democratic transition, the insufficiency of public services, and financial and administrative corruption.

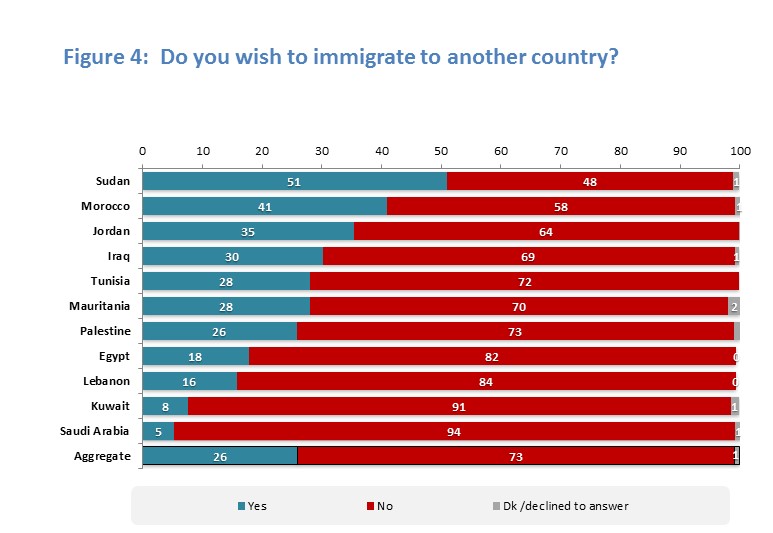

● 26% of Arabs want to immigrate to other countries. While a desire for economic improvement was the most cited incentive to emigrate across the Arab countries surveyed, approximately one-fifth of would-be emigres cited political reasons and concerns over safety and security. This was highly dependent on the subjective circumstances in the country surveyed; while the majority cited economic factors for their desire to emigrate, half of Iraqis and over a quarter of Palestinians cited security and political concerns as their desire to leave their home countries.

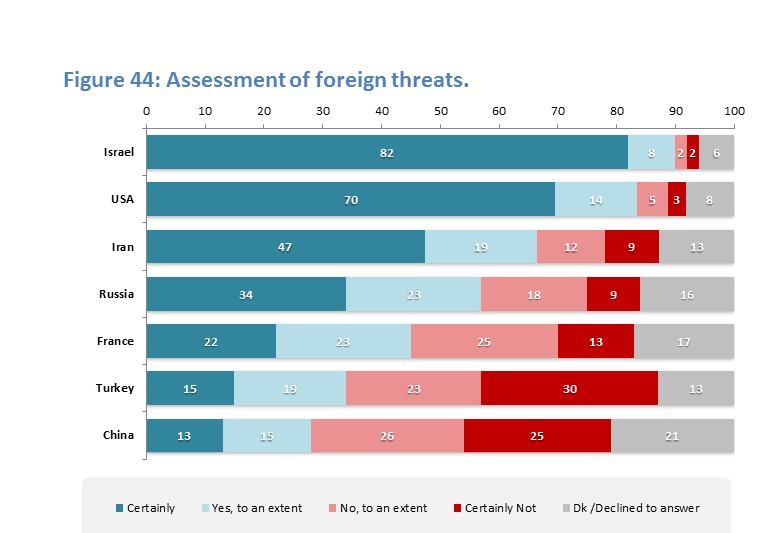

● Respondents in the Arab region provided a variety of different answers when asked to name the country which posed the largest threat to their national security. Israel was the most cited threat to the national security of their home countries. The second most-cited country was the United States. Finally, the third-most cited country in 2017-2018 was Iran.

Section 2: Perceptions of State Institutions and Governmental Effectiveness

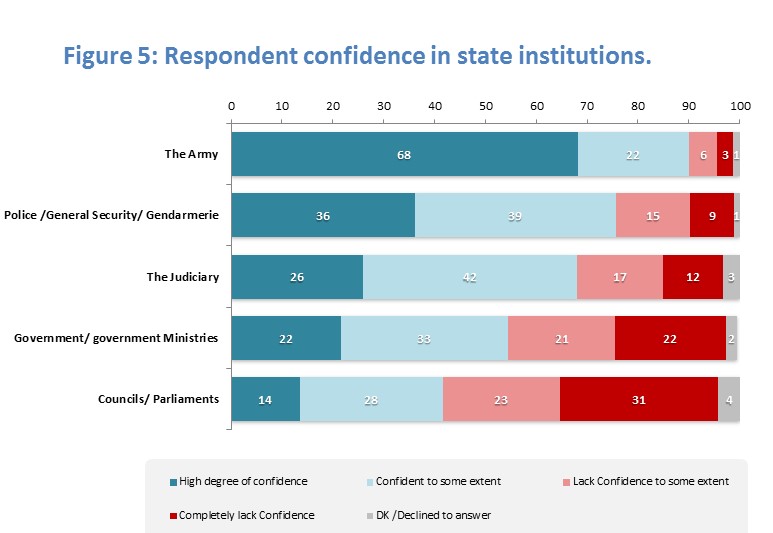

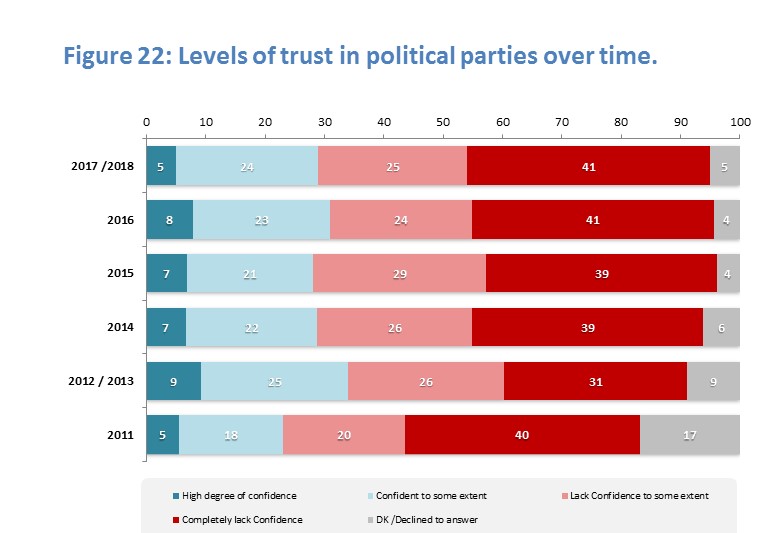

● Results from the 2017-2018 Arab Opinion Index reflect a generally low level of public confidence in Arab governments and civilian government institutions. People showed the least confidence in political parties. In contrast, the Arab public generally has a high level of confidence in their militaries as well as police/general security.

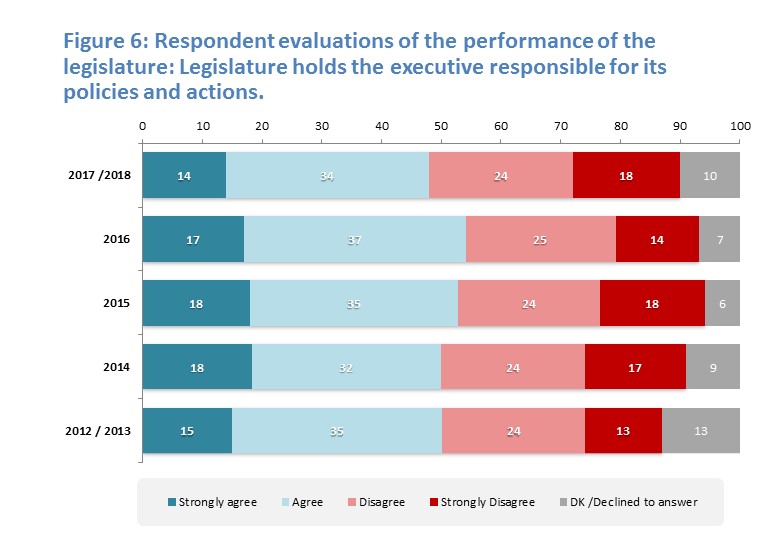

● 48% of the Arab public is evaluates the performance of the legislature positively, in their respective countries, whereas 42% evaluate the performance of the legislature negatively. This question specifically addressed the ability of the legislature to hold the executive accountable.

● In general, Arab public opinion regarding government performance is polarized. 55% of the Arab public has a negative view of their governments, while 43% have a positive view. It is important to note that there is wide variation on this issue by country.

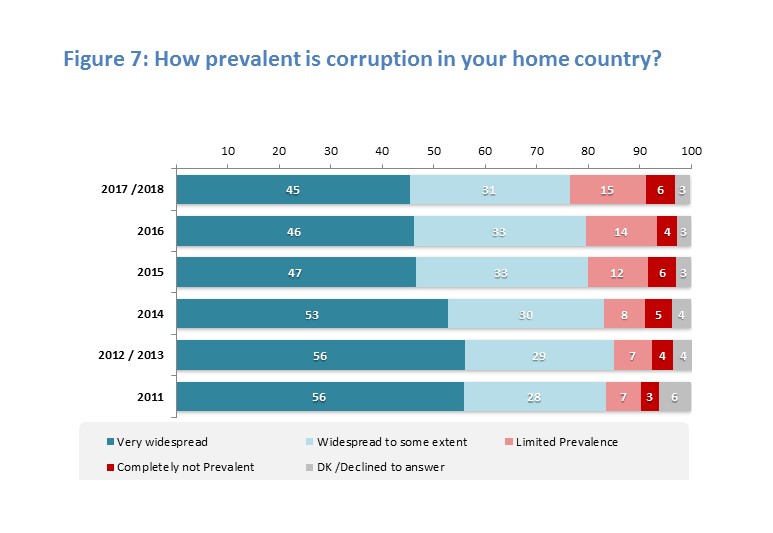

● There is a clear consensus among the Arab public that corruption is widespread across their countries: 91% of the Arab public believes that corruption is widespread in their home countries, compared to only 6% who believe that corruption is not widespread at all. Similarly, Arab public opinion is divided over the sincerity of Arab governments in tackling corruption. There has been little significant change in the perception of corruption, and its prevalence, over previous years.

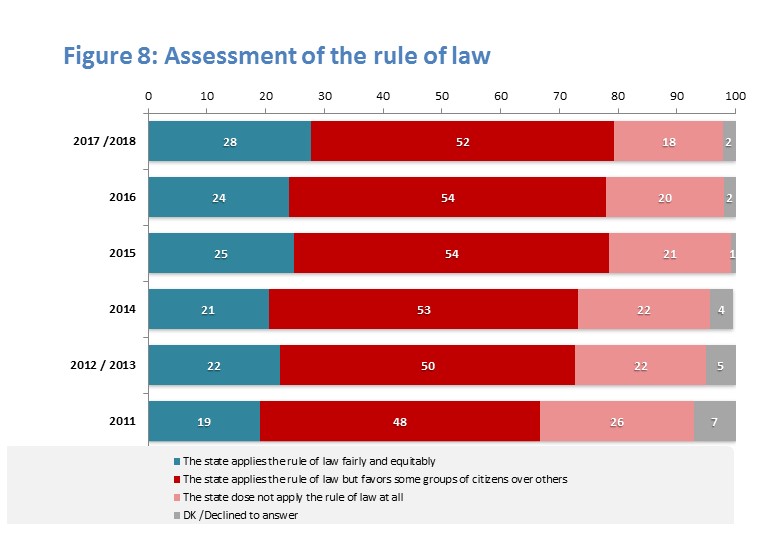

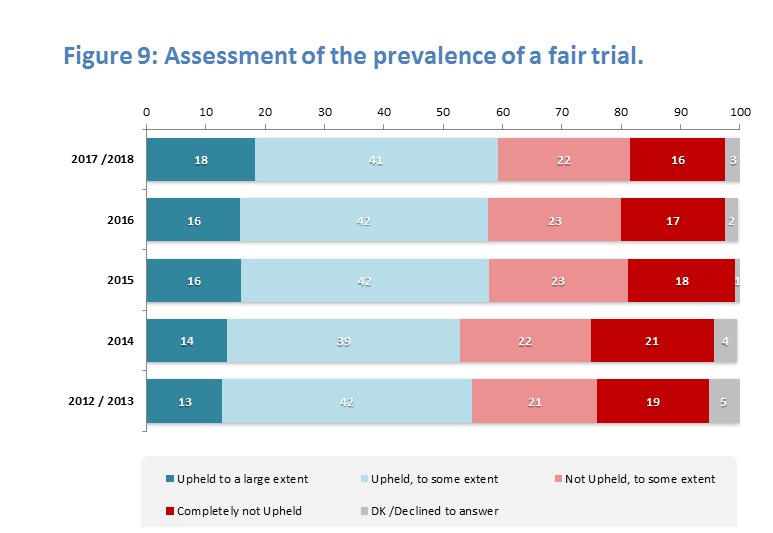

● Only 28% of the Arab public believes that the rule of law is applied universally in their home countries, without prejudice. 52% of the Arab public maintains that the rule of law is applied in their home states but that some groups are shown favorable treatment. Finally, 18% of Arabs expressed the opinion that the rule of law is not applied in their home countries at all. Similarly, 38% of the Arab public believes that the principle of a fair trial is not upheld in their home countries.

Section 3: Arab Public Attitudes towards Democracy

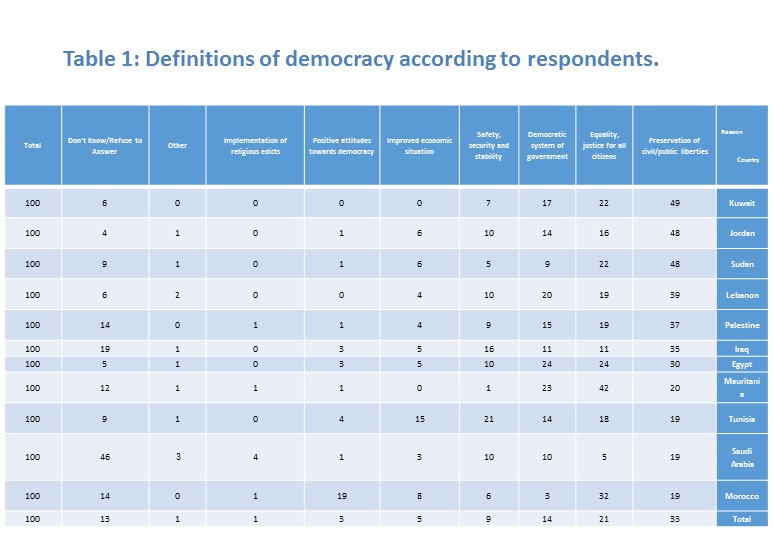

● Respondents to the 2017-2018 Arab Opinion Index define democracy in a variety of different and meaningful, coherent ways. 33% of the overall group of respondents gave answers which emphasized the safeguarding of citizens' political and civil liberties; 21% defined democracy as the guaranteeing of equality and justice between citizens; 9% gave answers that emphasized either safeguarding safety and security; and 5% the improvement of economic conditions. Another 14% of respondents provided answers which emphasized such points as the peaceful transition of power and institutional checks and balances.

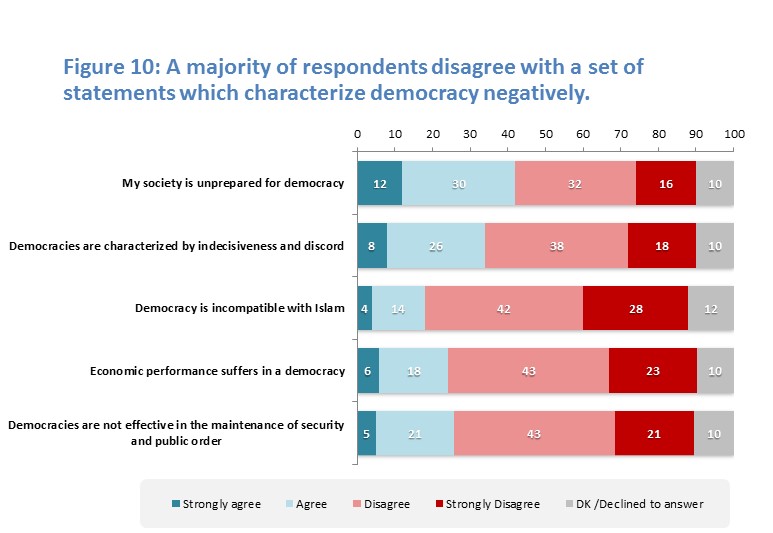

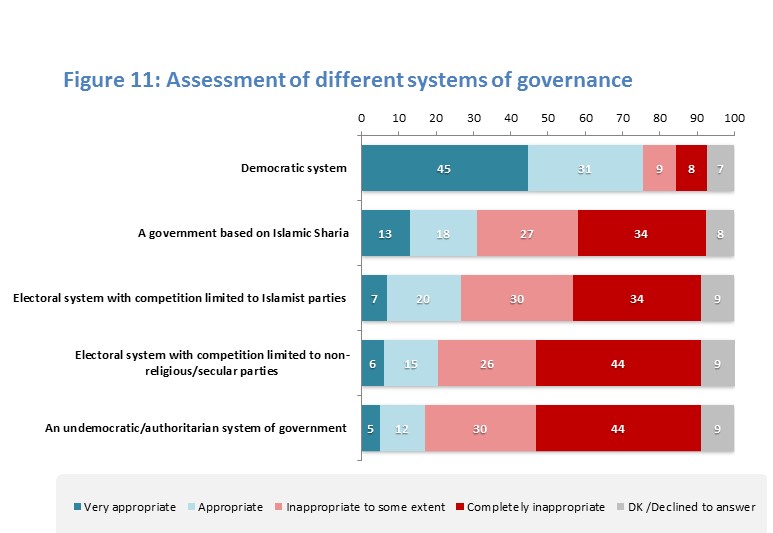

● A full 76% of Arabs believes that democracy is the most appropriate system of governance for their home countries, when asked to compare democracy to other systems (such as authoritarian regimes, representative democracies where electoral competition is limited to either Islamist or non-Islamist/secular political parties, or to theocracies). Additionally, a majority of Arabs disagree with a set of widespread statements which are often employed in public discourse to discredit democracy.

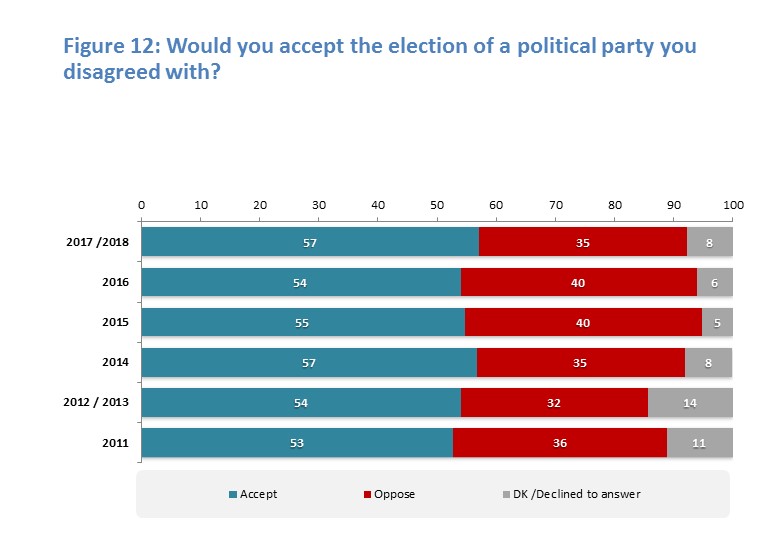

● A majority of Arab citizens, 57%, would accept an electoral victory and rise to power of a political party which they disagreed with, while 35% stated that they would be opposed to the ascendancy of a political party with which they disagreed.

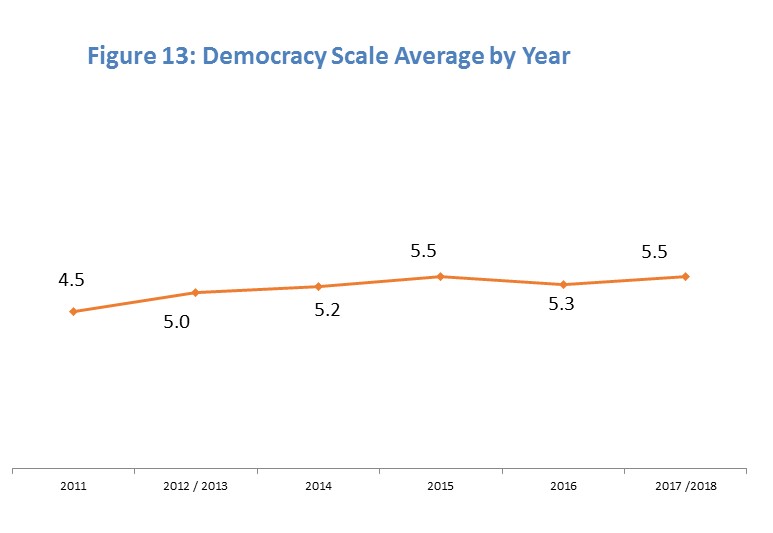

● When asked to rate the level of democracy in their home countries on a numeric scale from 1 to 10--with 1 being "completely undemocratic" and 10 being "democratic to the greatest extent possible"--respondent evaluations averaged to 5.5. Across individual countries, there was wide variation, from 7.5 to 3.7.

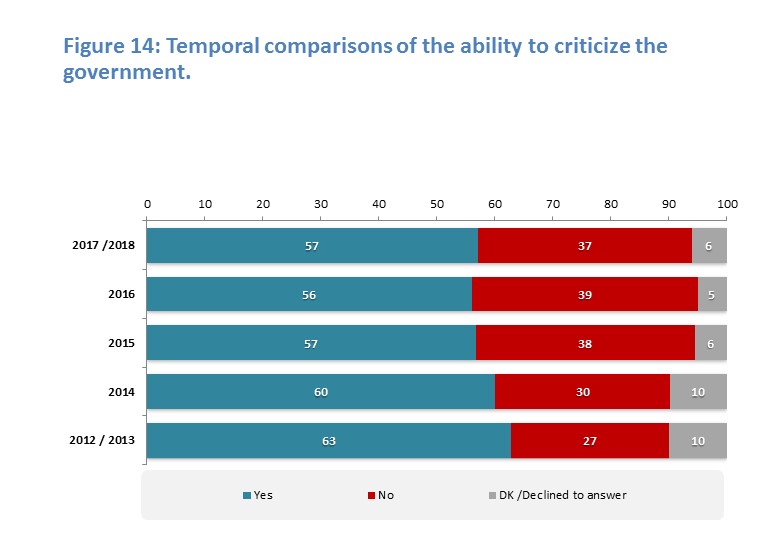

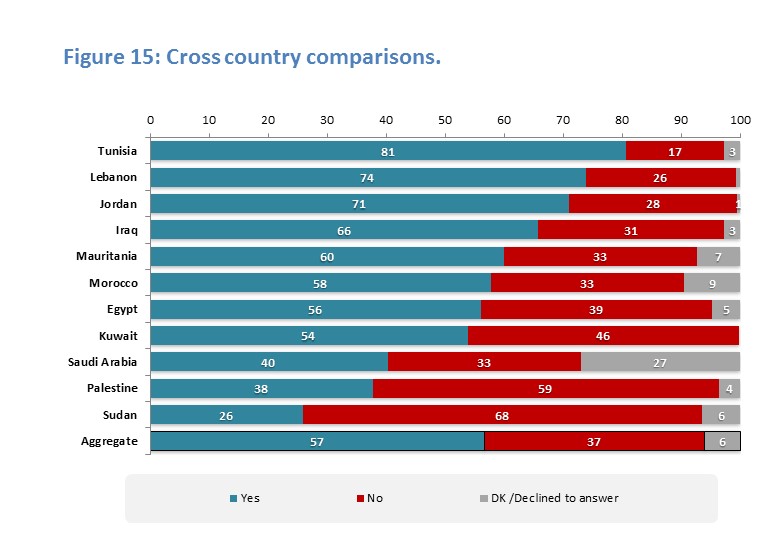

● When asked if the citizens of their home country were free to criticize their government without fear of retribution, 37% of the Arab public said this was impossible to do. Indeed, in some countries, such as in Palestine and Sudan, majorities expressed the view that they were not free to openly criticize their own governments without fear (59% and 68% respectively).

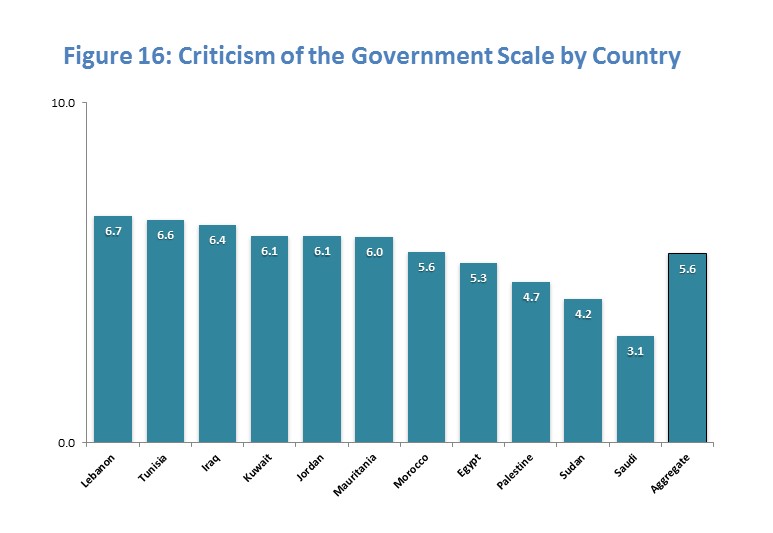

● We also asked the question of how much they are able to criticize the government using a sliding scale, with 1 being the least ability and 10 being the most ability. The average number was 5.6 regionally, with respondents in Saudi Arabia being predictably the least able to criticize the government, and respondents in Lebanon and Tunisia being the most.

How does public opinion gauge the 2011 Arab uprisings?

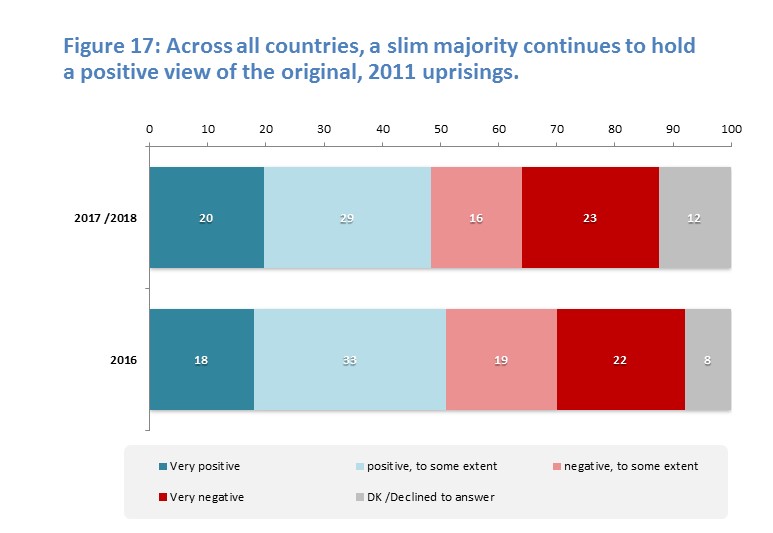

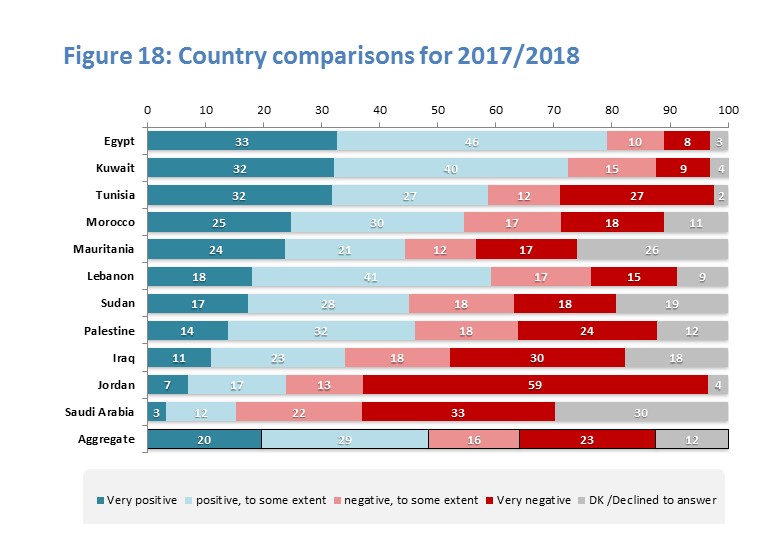

- In the context of identifying public attitudes toward democracy, we also gauge public opinion on the Arab uprisings of 2011, the main demand for which was to end tyranny. Thus, to assess the views of citizens on the revolutions at the moment of their happening, without asking about subsequent developments, we asked: "Back in 2011, several Arab countries witnessed revolutions and popular protests, in which people took to the streets in demonstrations. What is your assessment of that?"

- Results showed that 49% still consider the uprisings to have been positive, and 39% consider them to have been negative.

● 49% of the Arab public still views the Arab Spring revolutions positively, compared to 39% that said it was negative. 30% of the sample declined to answer.

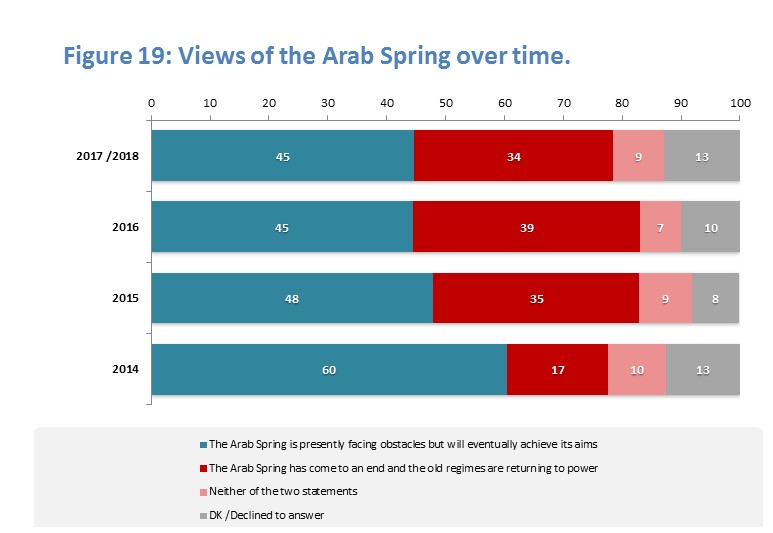

● The Arab public is neatly divided in terms of its outlook towards the future path of the Arab Spring: 45% maintain that these revolutions will ultimately achieve their aims, even if they are now going through a difficult phase. In contrast, 34% of Arabs believe that the Arab Spring has been aborted before the revolutions could achieve their aims, and that the former regimes have returned to power. This is a marked decline from 2014, when two-thirds of the Arab public was openly optimistic about the Arab Spring eventually achieving its aims. Some reasons for this growing disenchantment include creeping authoritarianism and the spread of chaos in many of the Arab Spring countries.

Section 4: Civic and Political Participation

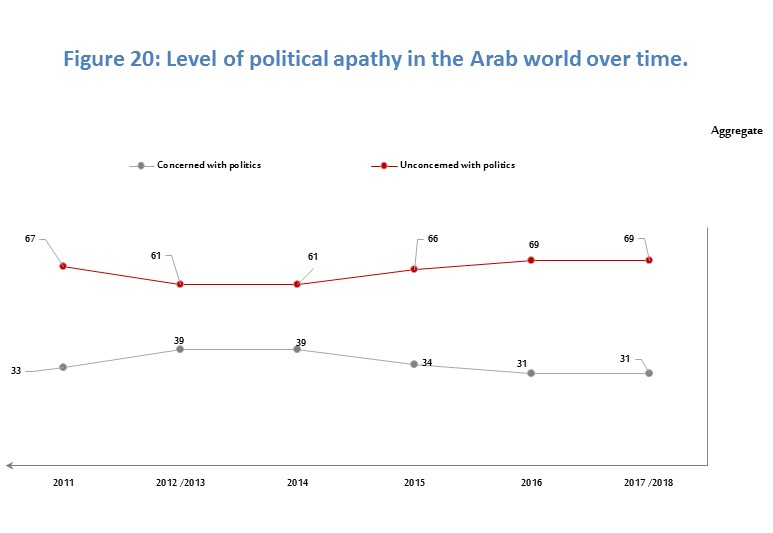

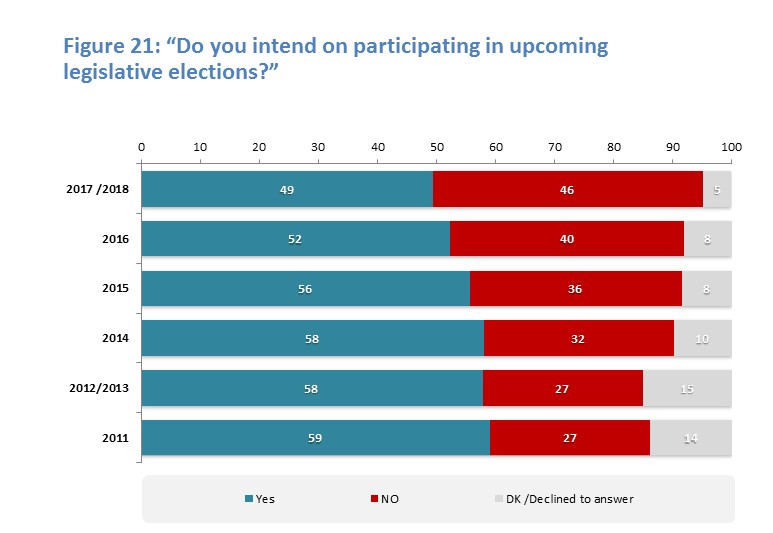

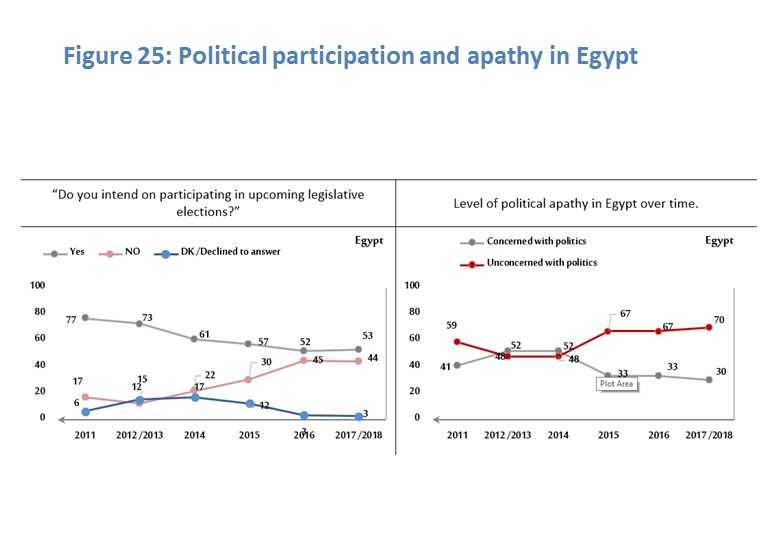

● Despite the fact that citizens in the Arab world support democracy, their political and civic participation is limited. To assess this issue, we tested three operationalizations of political participation, including: political apathy, their trust in existing political parties, and whether or not they plan on participating in upcoming elections.

● The results show a decrease in concern for politics, as it has been reduced to 31% versus 69% who self-identify as politically apathetic.

● Public opinion was split regarding participation in elections. Those who said they do not want to engage in elections has risen to 46%, although this figure hovered around 27% in the surveys from 2011 to 2013.

● Trust in political parties has also decreased over the years.

● Although Arab public opinion supports democracy and gauges the level of democracy in their countries negatively, it is clear that political apathy has become increasingly the norm. This is perhaps to be expected if we are to consider that the common citizen does not have space to criticize the government. Egypt is a prime example of this dynamic.

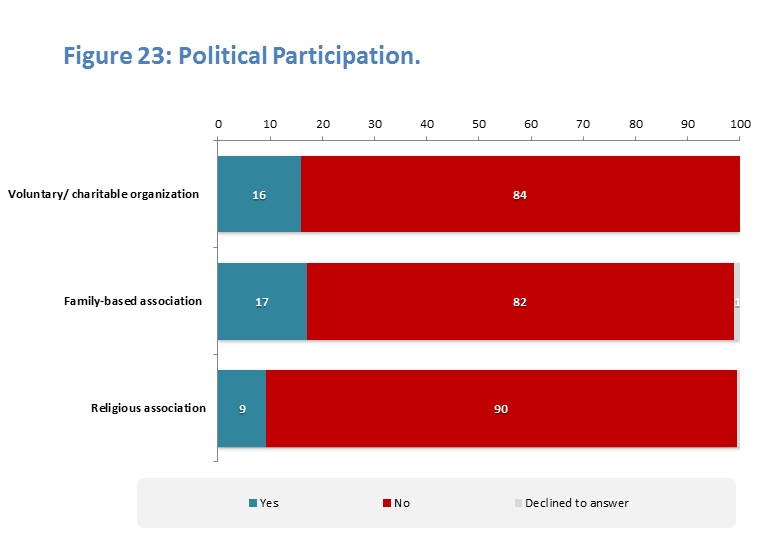

● Membership of and participation in civil and voluntary organizations remains extremely limited across the Arab region, with no more than 16% of respondents reported that they are members of such groups in any given country. When taking into account the level of active participation in the activities of such groups, the level of effective participation would likely fall further still.

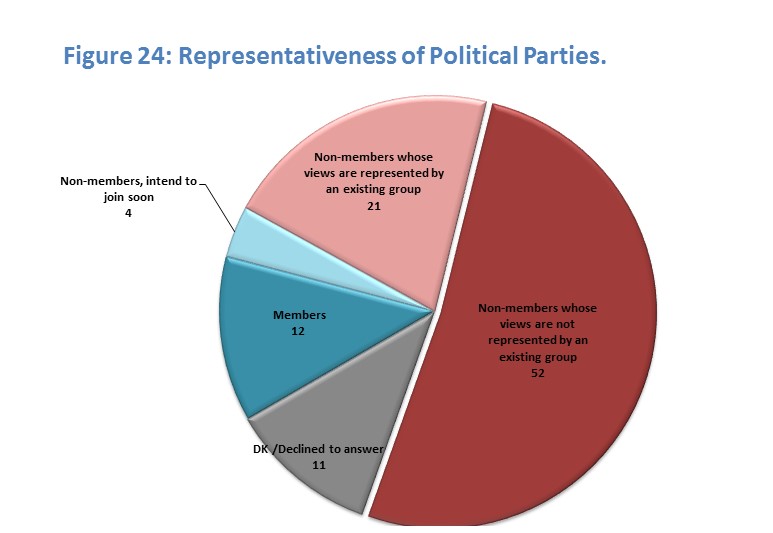

● Additionally, a majority of Arabs (52%) have no affiliation with a political party in any way, nor do they feel that their views are represented by any existing political group or bloc. Respondents who reported that they were either members of political parties or that there was a political party which they felt was representative of their views, were concentrated in Mauritania, Morocco, Tunisia, Palestine, Iraq and Lebanon.

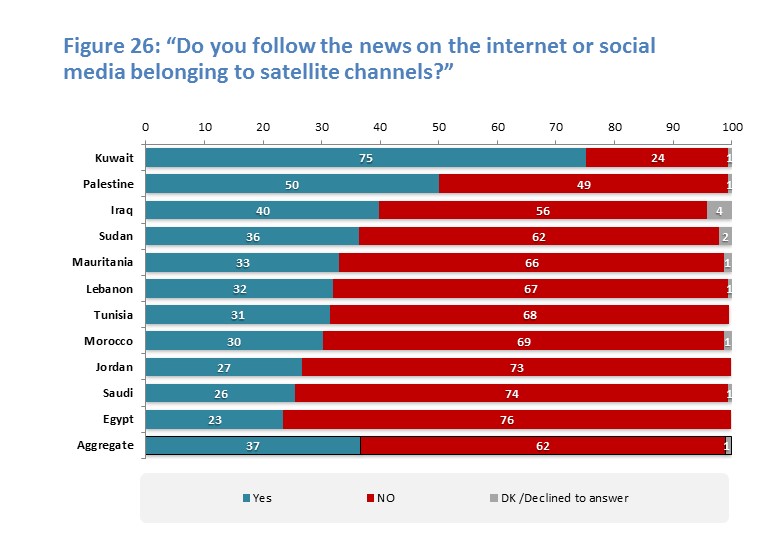

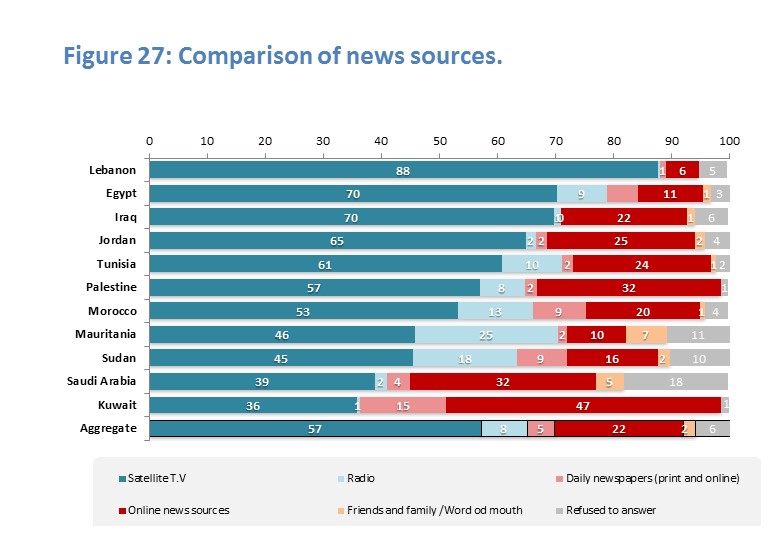

● When it comes to following political news, we find that countries which have high rates of political apathy and no room for criticism are the ones that follow political news the least (i.e. Saudi Arabia and Egypt). Alternatively, in countries with more open political systems, people are more concerned with following political news.

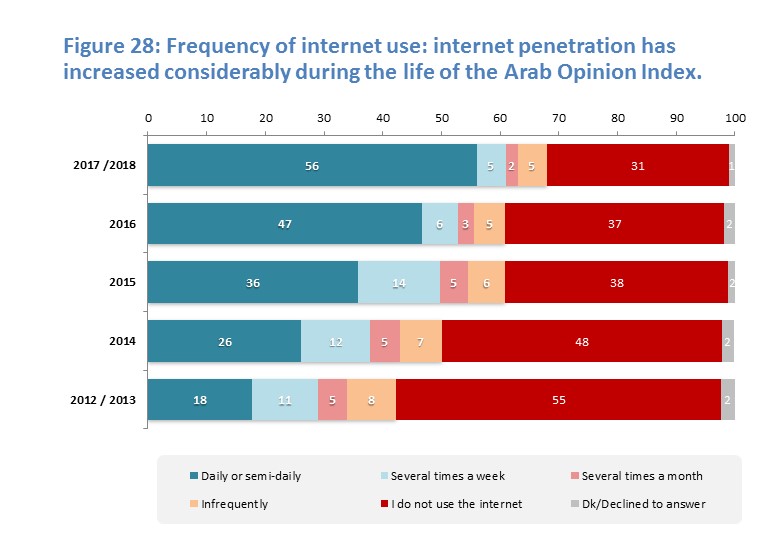

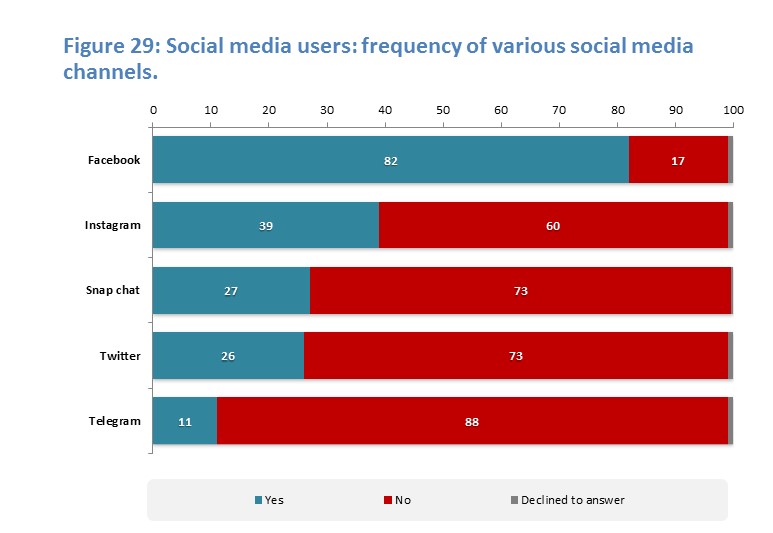

● While 68% of respondents reported using the internet, to varying extents, fully 31% indicated that they never use the internet. The results from the 2017-2018 poll show a continuing, statistically significant increase in internet penetration in the Arab region. The vast majority of Arabs who use the internet also have accounts on Facebook, at 82%, while 26% have accounts on Twitter. The relative popularity of various social media can be seen in the chart below.

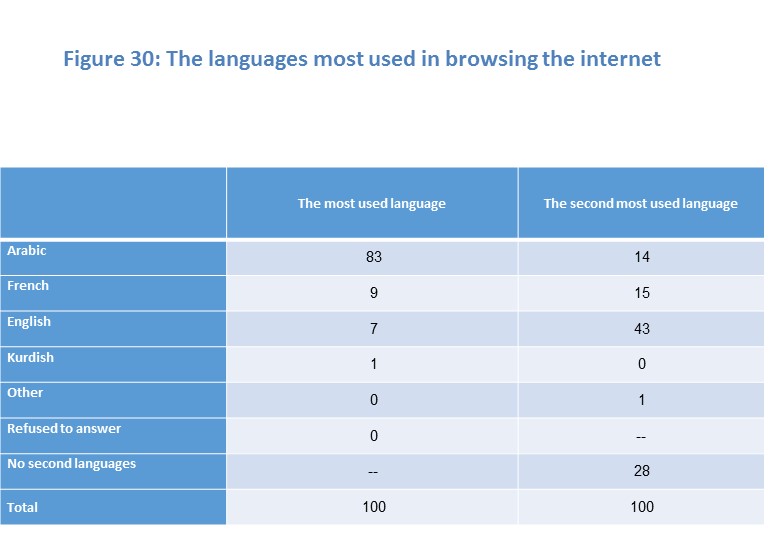

● The most used language while browsing the internet was predictably Arabic, with English being the second most used.

Section 5: Religion and Religiosity in Public Sphere and Political Life

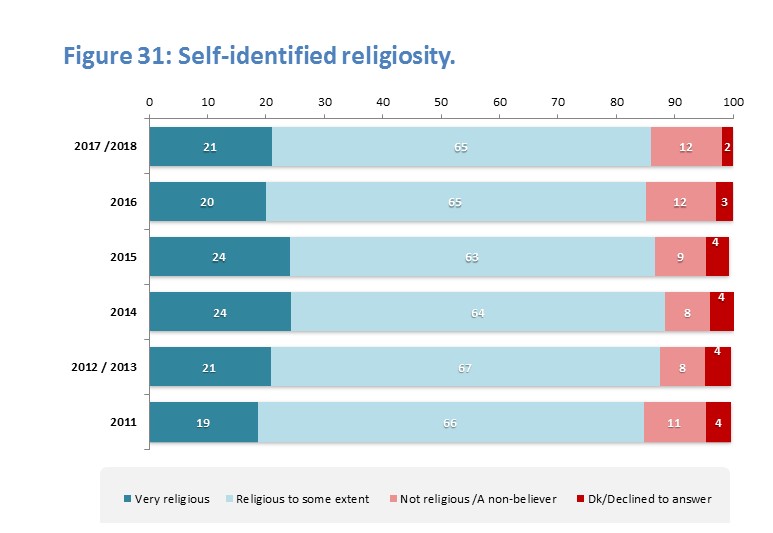

● Based on self-reporting, a majority of the Arab public is "Religious to some extent" (65%). This compares with 11% of the Arab public who define themselves as "Not religious," and 21% as "Very religious."

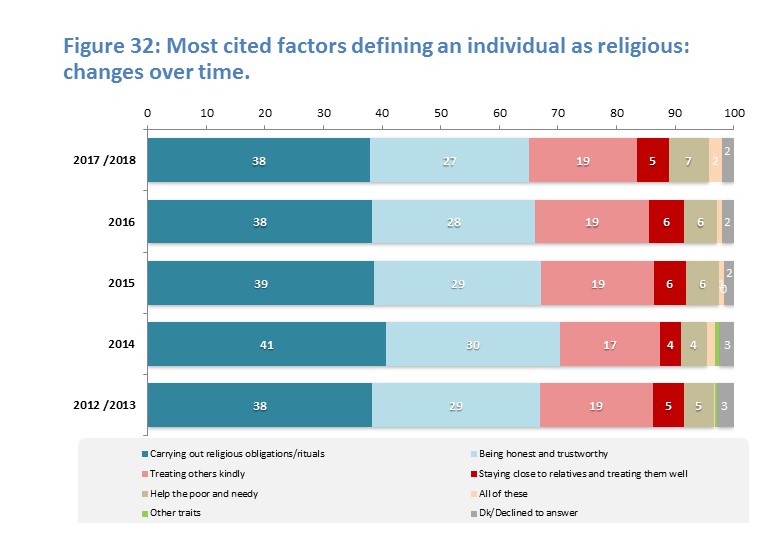

● When asked to define the attributes which define religiosity, most respondents provided answers that focused on an individual's morality and values rather than the observance of religious practices (38%). This value has not changed significantly since 2011.

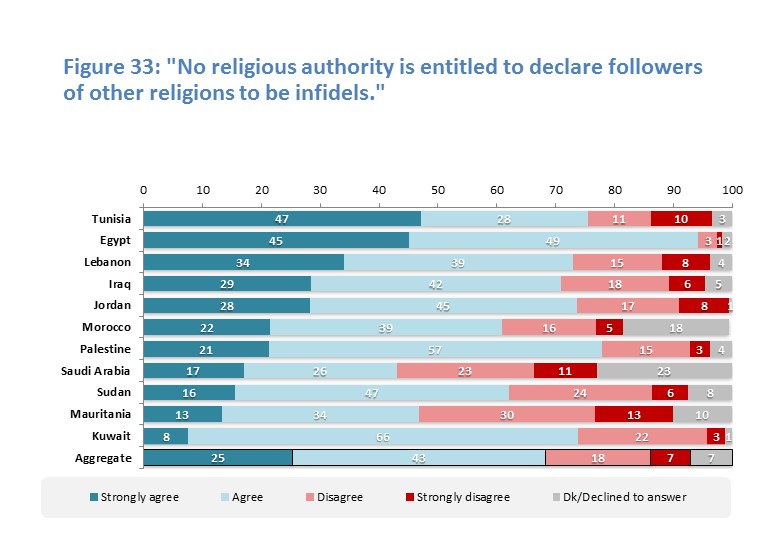

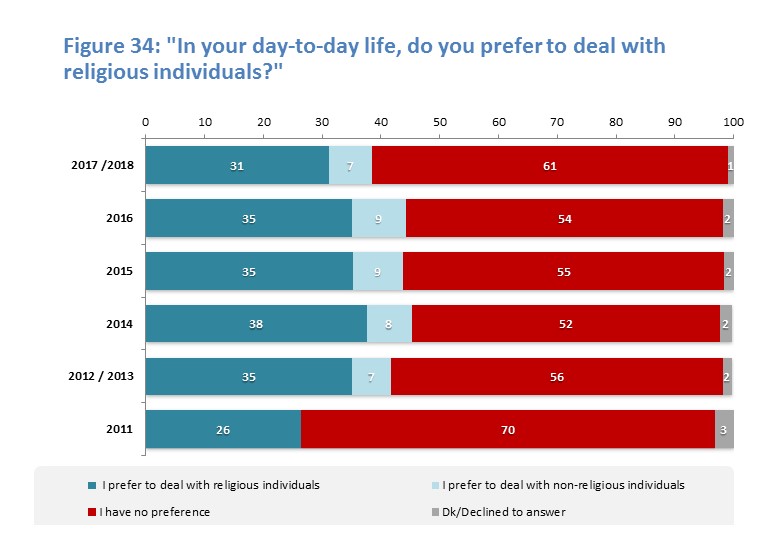

● While most Arabs describe themselves as religious, the majority of respondents nonetheless oppose edicts which pass negative judgement against members of other faiths, or which declare followers of differing interpretations of Islam to be apostates. Most respondents, while religious, refuse to accept that non-religious people are by definition bad people. Finally, most respondents do not discriminate on the basis of religiosity, between religious and non-religious individuals, when conducting their social, political and economic/business interactions. The issue has become more polarized, however, since the percentage of people who profess no preference decreased from 70% to 61%.

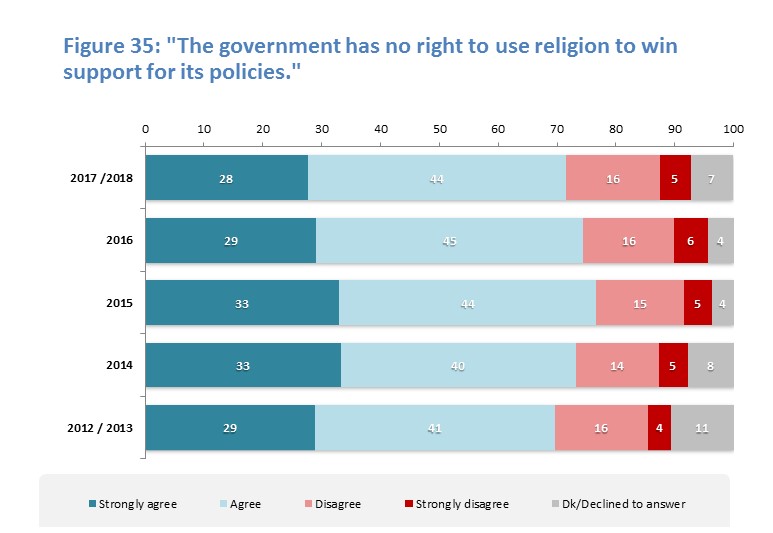

● Most Arabs oppose the involvement of clerics in voter choice or in governmental policy. Similarly, a majority of Arabs are opposed to the employment of religion either by governments in order to win support for their policies, or by electoral candidates to win votes.

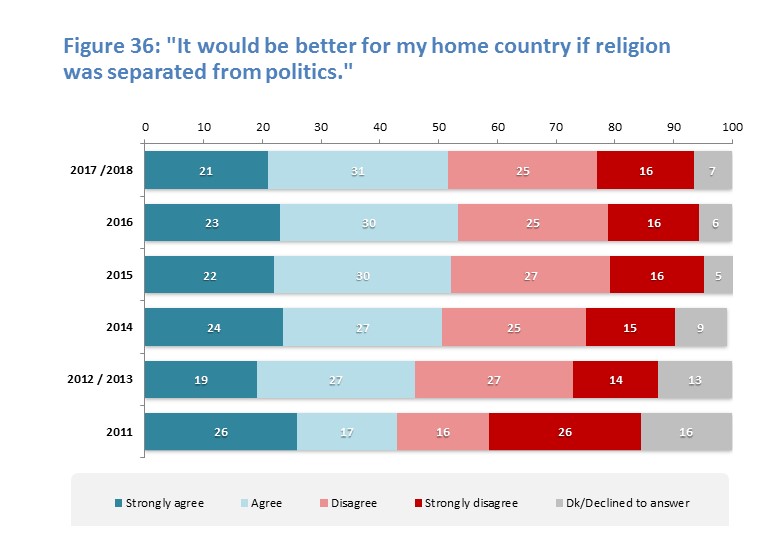

● Arab public opinion is split almost in half in their attitudes towards the general "separation of religion from the state," although only a simple majority (around 52%) supports the principle of separation of religion from political life. This means Arab publics do not want a fully secular system, and do agree there is space for religion in political life.

Section 6: Arab Public Opinion and Intra-Arab Relations

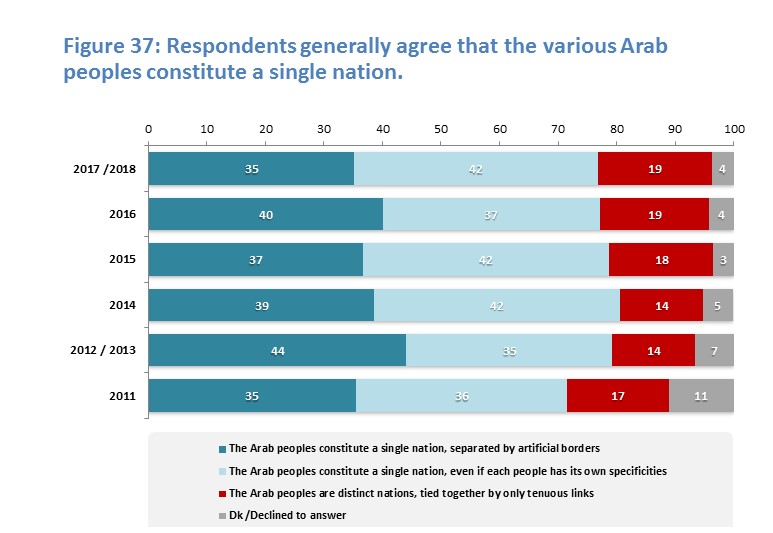

● A total of 77% of the respondents to the 2016 Arab Opinion Index supported the sentiment that the various Arab peoples formed a single nation, in contrast to only 19% who agreed with the statement that "the Arab peoples are distinct nations, tied together by only tenuous bonds."

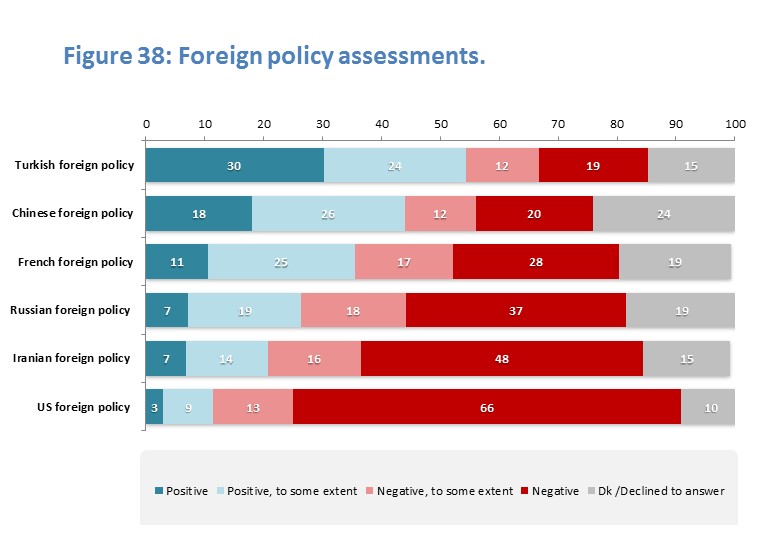

● Arab public attitudes towards the foreign policies of regional and global powers towards the Arab region are broadly negative. Around 79% of respondents held negative views of US foreign policy towards the Arab countries; 64% had negative views of Iran's Arab policies; and 55% expressed negative views of Russia's policy towards the Arab states. During 2017-2018, Arab public attitudes towards US foreign policy recorded their most negative levels.

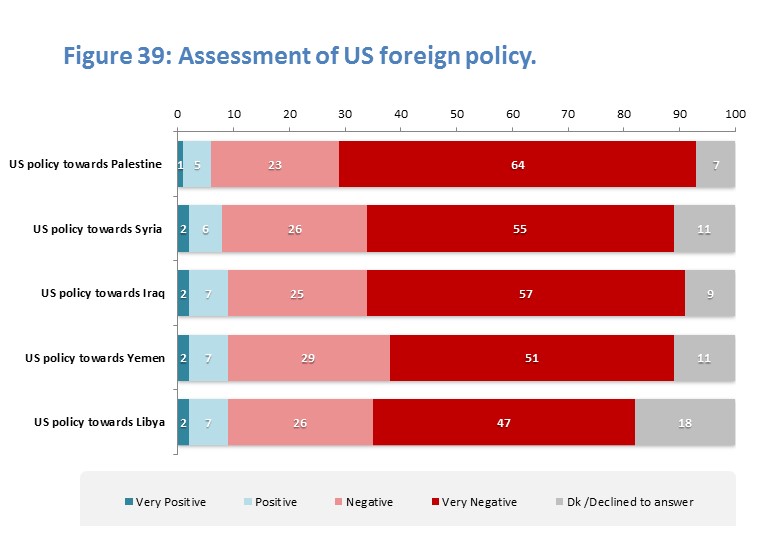

● When asked to look at specific US foreign policy areas, vast majorities of Arabs had negative views of US policy towards Palestine (87%, up from 79% last year); Syria (81%) and Iraq (82%).

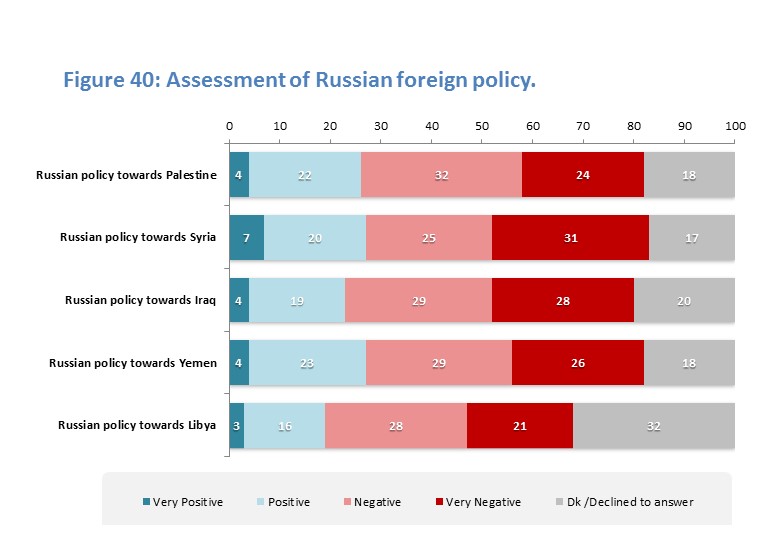

● When asked to look at specific Russian foreign policy areas, approximately half of Arab respondents have negative views of Russian policy towards Palestine, Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Libya.

● When asked to look at specific Russian foreign policy areas, approximately half of Arab respondents have negative views of Russian policy towards Palestine, Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Libya.

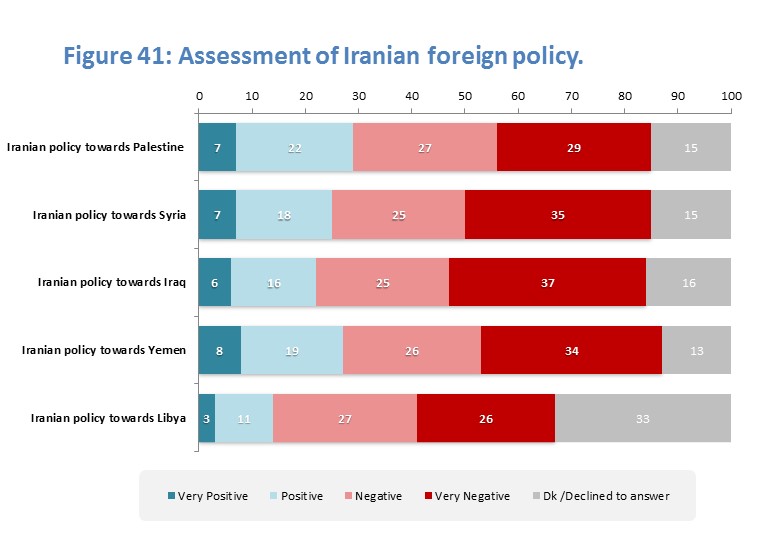

● When asked to look at specific Iranian foreign policy areas, over half of Arabs have negative views of Iranian policy towards Palestine, Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Libya.

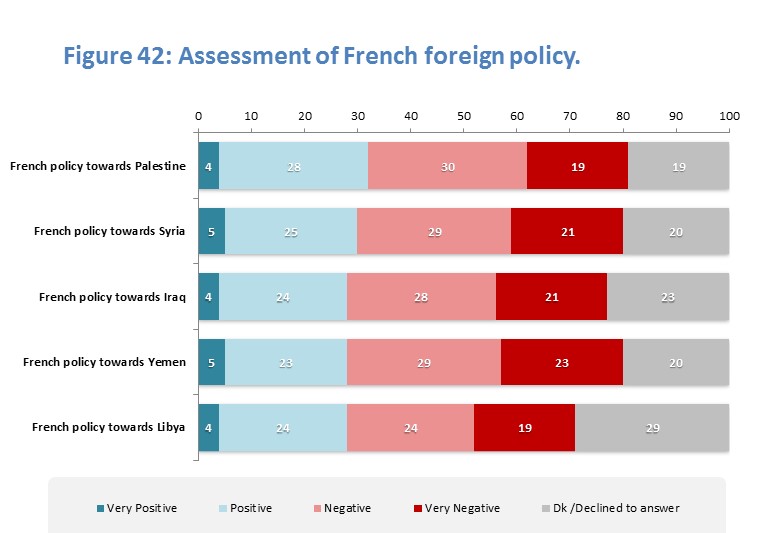

● When asked to look at specific French foreign policy areas, strong majorities (between 57% and 59%) of Arabs have negative views of French policy towards Palestine, Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Libya.

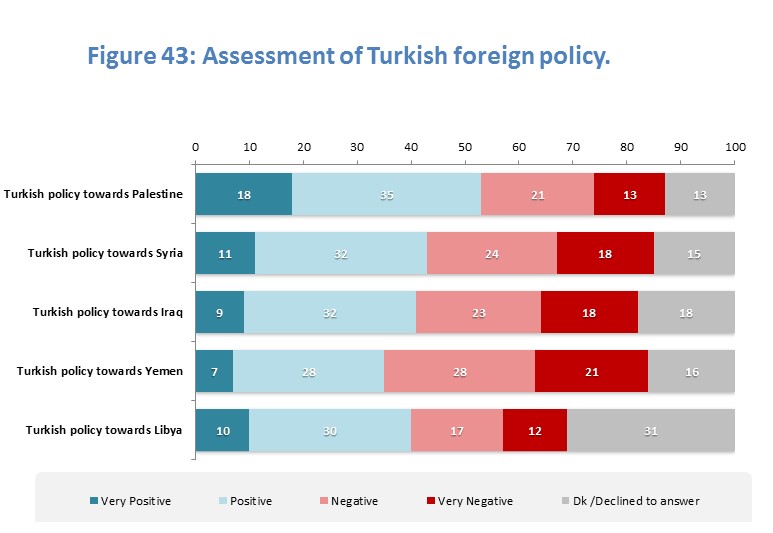

● In contrast, the Arab public is roughly equally split in its perceptions of Turkish foreign policy in Syria and Iraq: roughly 43% view Turkey's Syria positively, compared to another 42% who view it negatively. In Iraq, the comparable figures are 41% (positive views) and 41% (negative views). Meanwhile, 53% of the Arab public had positive views of Turkey's policies towards Palestine, compared to 34% who had negative views of Ankara's policies.

● Fully 90% of Arabs believe that Israel poses a threat to the security and stability of the region.

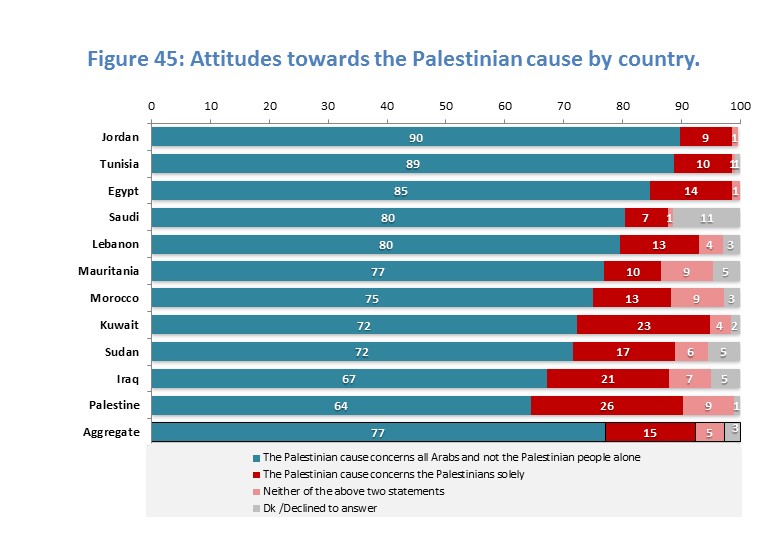

● Over three quarters of the Arab public agree that the Palestinian cause concerns all Arabs, and not the Palestinians alone. Most Arabs also disapprove of the various peace treaties signed between a number of Arab states and Israel: this applies to respondents' views of the Oslo Agreements (Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization), the Camp David Accords (Israel and Egypt) and the Wadi Araba Agreement (Israel and Jordan).

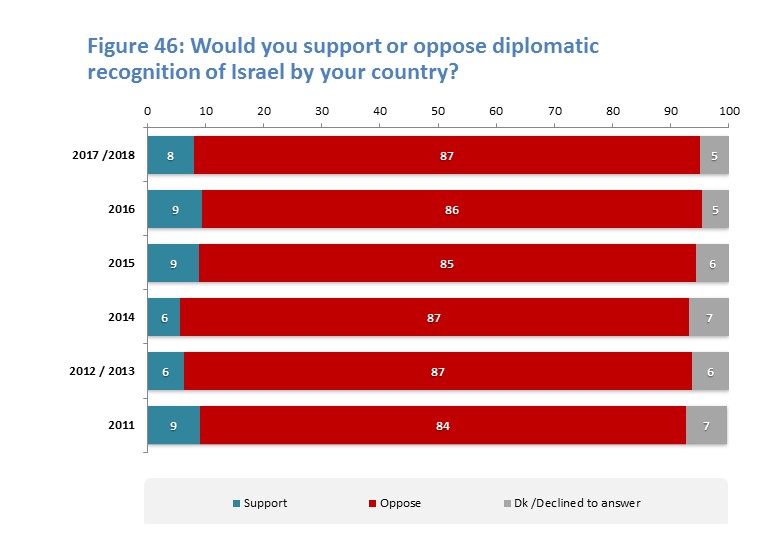

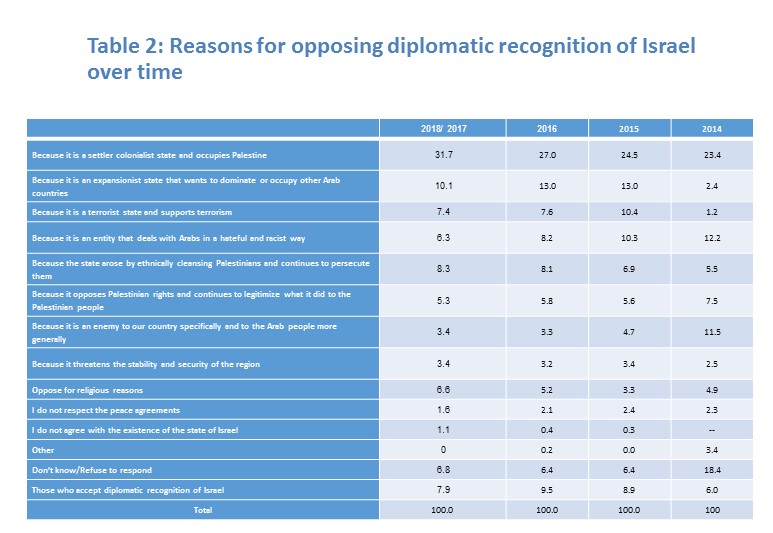

- An overwhelming majority (87%) of Arabs would disapprove of recognition of Israel by their home countries, with only 8% accepting formal diplomatic recognition. In fact, one half of those who accepted recognition of Israel by their governments made such recognition conditional on the formation of an independent Palestinian state. When asked to elaborate on the reasons for their positions, respondents who were opposed to diplomatic ties between their countries and Israel focused on a number of factors, such as Israeli racism towards the Palestinians and its colonialist, expansionist policies.

Section 7: Arab Public Opinion towards ISIL

● Almost all respondents (98%) indicated that they were aware of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as the "Islamic State of Iraq and Syria" and "the Islamic State").

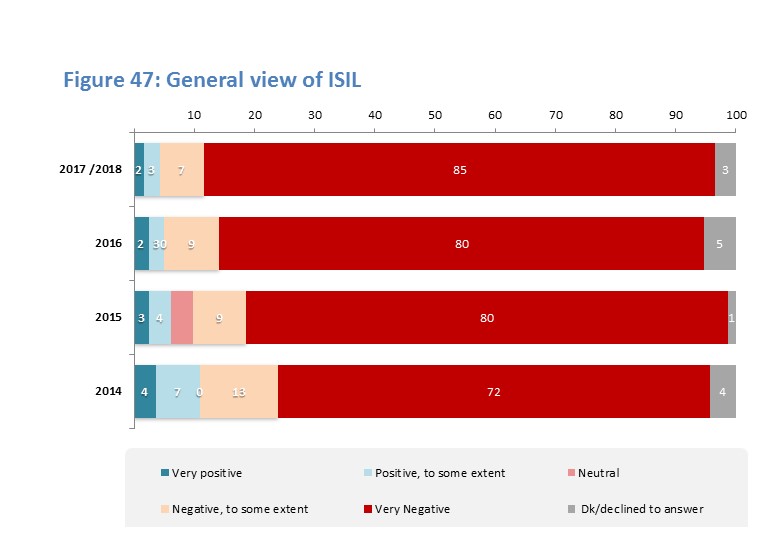

● An overwhelming majority of 92% of the Arab public does has a negative view of ISIL, with 2% expressing a "positive" view, and 3% "positive to some extent".

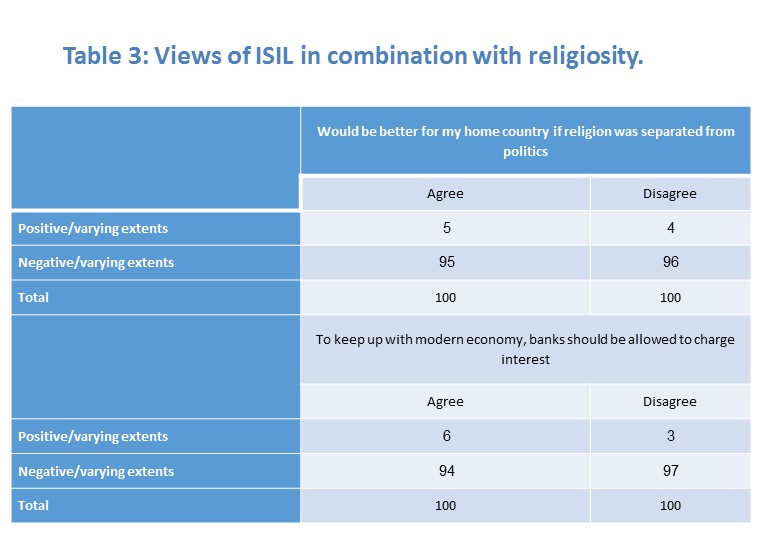

● Crucially, favorable views of ISIL were not correlated with religion: respondents who identified themselves as "Not religious" were just as likely to have favorable views of ISIL as those who identified as "Very religious". Similarly, no relationship could be shown between respondents' opinions of ISIL and their views on the role of religion in the public sphere. In other words, public attitudes towards ISIL are defined by present-day political considerations and not motivated by religion.

● To explore Arab public opinion about factors contributing to the emergence of ISIL, the Arab Index included a number of new questions. When asked to explain the reasons behind ISIL's popularity among its support base, 13% of respondents stated that this was due to its "military accomplishments". This was followed by 16% who attributed ISIL's popularity amongst its supporters to its claimed adherence to Islamic principles; 11% to the group's willingness to confront the West; and 10% to the group's ability to defend the Sunni Muslim community. Ultimately, a majority of Arabs credit ISIL's military accomplishments and its stances on current political issues as the source of its authority and popularity.

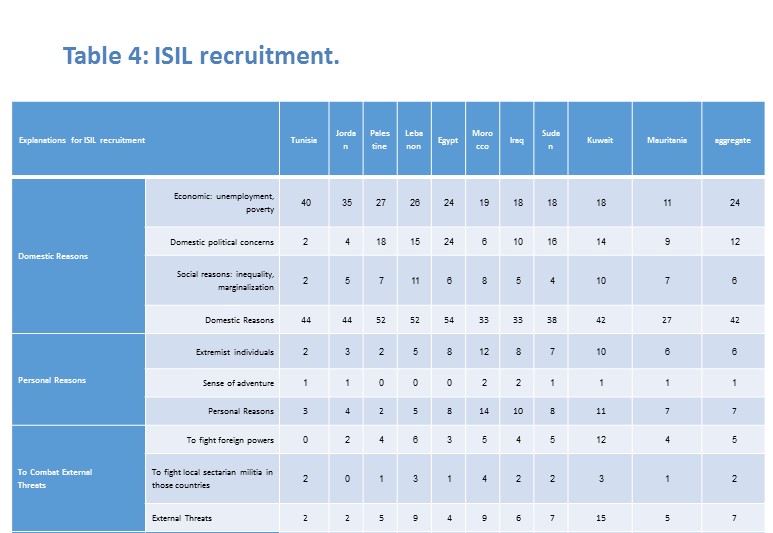

● When asked to explain which factors would drive citizens of Arab countries to join ISIL, a number of varying reasons were given. These were rooted in the government policies and political instability of their home countries (42%) and economic difficulties (24%), while 6% explained the enlistment of Arabs into ISIL on social grounds, such as inequality, marginalization and social exclusion. A further 18% credited "brainwashing" and "propaganda" as the reasons for Arabs to join ISIL, while a final 6% described the chance to fight foreign powers and/or sectarian militia in Syria and Iraq as the motive for young Arabs to fight ISIL.

Table 4: ISIL recruitment.

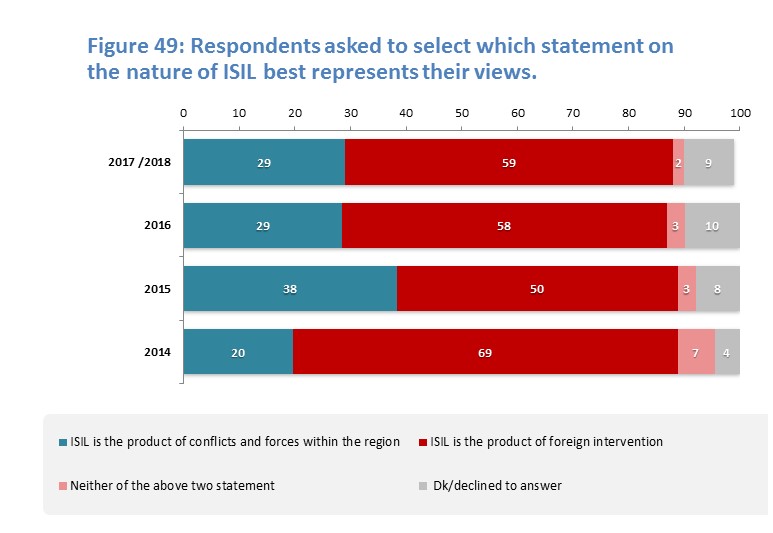

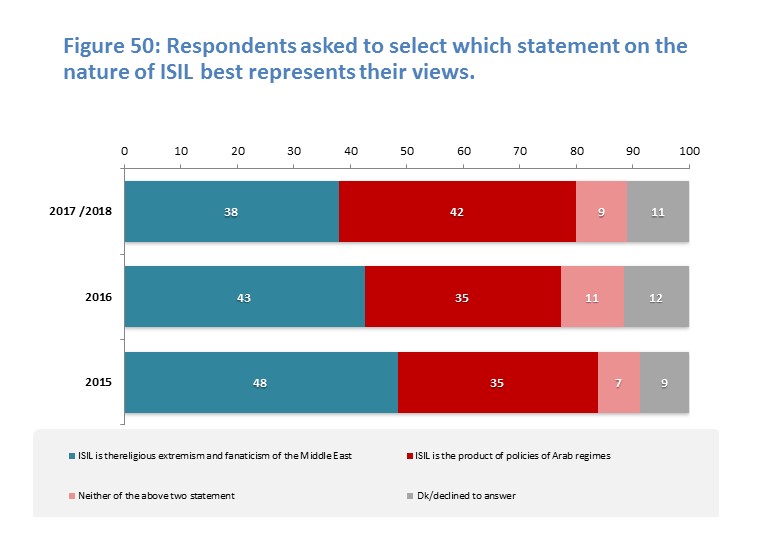

● When asked if the existence of ISIL was either the result of internal factors endemic to the region or the result of foreign activity, only 29% of respondents expressed the view that the group's existence resulted from the internal conflicts extant in the Middle East, compared to 59% who attributed ISIL's existence to the policies of foreign powers. When presented with another two statements regarding the origins of ISIL, 42% of respondents were prepared to attribute the rise of ISIL to the extremism inherent in Middle Eastern societies while 38% attributed the rise of ISIL to the policies of Arab regimes.

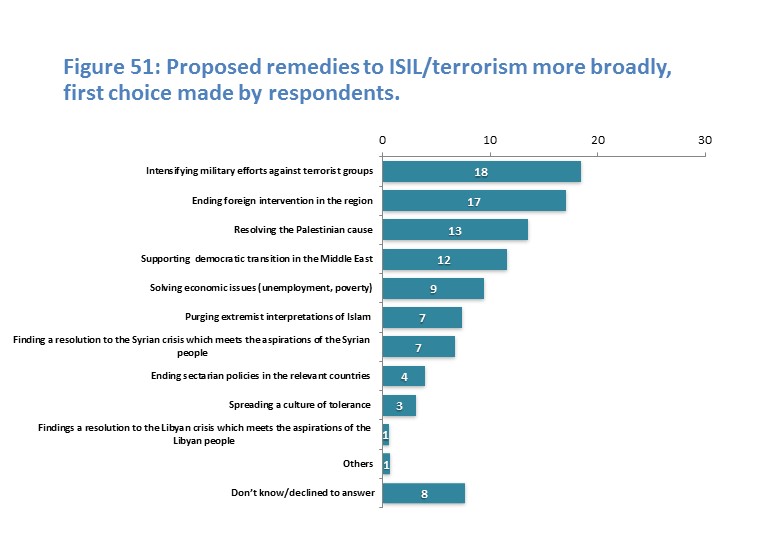

● The Arab public offers a diverse set of remedies when asked to suggest the best means by which to combat ISIL, when given the chance to define their first and second preferences for the means to tackle ISIL in particular, and also terrorist groups more broadly: direct military action was the most widely selected first choice, with 18% of respondents; ending foreign intervention in Arab countries was selected as the first choice by 17% of respondents; and 13% proposed resolving the Palestinian cause.

For the full PDF click here.