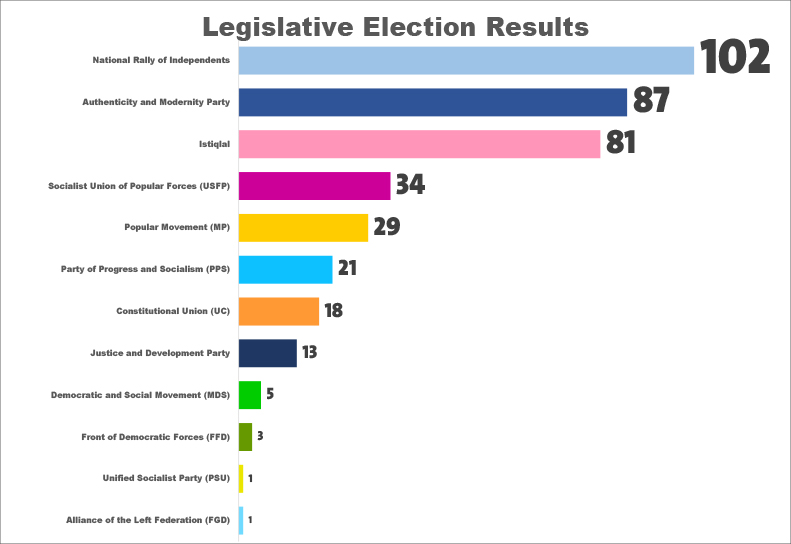

On 8 September, Morocco held its third general election since the 20 February movement, ten years after the adoption of the 2011 constitution. The election included the House of Representatives and municipal elections, as well as the House of Councillors (the second chamber) in one day, instead of holding two rounds in the same year in a cost cutting drive. The National Rally of Independents (RNI) came in first place, winning 102 seats out of the 395 seats in parliament, while the Justice and Development Party (PJD), which led the previous two governments, suffered a major defeat, ranking eighth with only 13 seats, down from 125 seats in the previous parliament.

Electoral Context

The elections took place during a stifling economic crisis, coinciding with the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has caused great damage to vital sectors, the most significant being tourism. An ongoing drought has also dealt a major blow to the agricultural sector. The crisis was exacerbated by imbalances in the contractual employment system that Morocco adopted in response to the recommendations of international monetary institutions, which resulted in a wave of protests that have affected educational institutions in particular.

Politically, the elections took place in the shadow of intense polarization between the so-called “administration” parties — RNI, led by businessman Aziz Akhannouch, and the Authenticity and Modernity Party (PAM) founded by Fouad Ali El Himma before he left to serve as an advisor to the king — and the Islamist PJD. PJD complained that it had been targeted by changing the electoral law, which calculates the allocations of seats based on the number of registered voters, rather than the number of those who actually cast a ballot, as has been the case since the 2002 elections. The party, which has led the government for two consecutive terms (2011-2021), considers this an attempt to deprive it of its leadership of the government, while other parties argued that the law supports the smaller parties, and condemned the PJD’s continued defeatist “grievance” discourse to cover up its loss.[1]

Although some political forces and parties called for a boycott of the elections, calling them a tool to legitimize what they called “practices of actual power,” the impact of these calls was limited. They were led by the Al Adl wal Ihsane association,[2] and the Democratic Way, a radical marxist party, which issued several communiqués denouncing the authorities' repression of its affiliates, and the confiscation of their banners, to prevent them from campaigning for a boycott of the elections.[3]

The Electoral Data

31 parties participated in the legislative and municipal elections, most notably PJD (leader of the government coalition), the RNI (participant in the government coalition), and the Istiqlal and PAM parties (both opposed to PJD).[4] The figures published by the Ministry of Interior on the elections show the following:

1- Voter Turnout

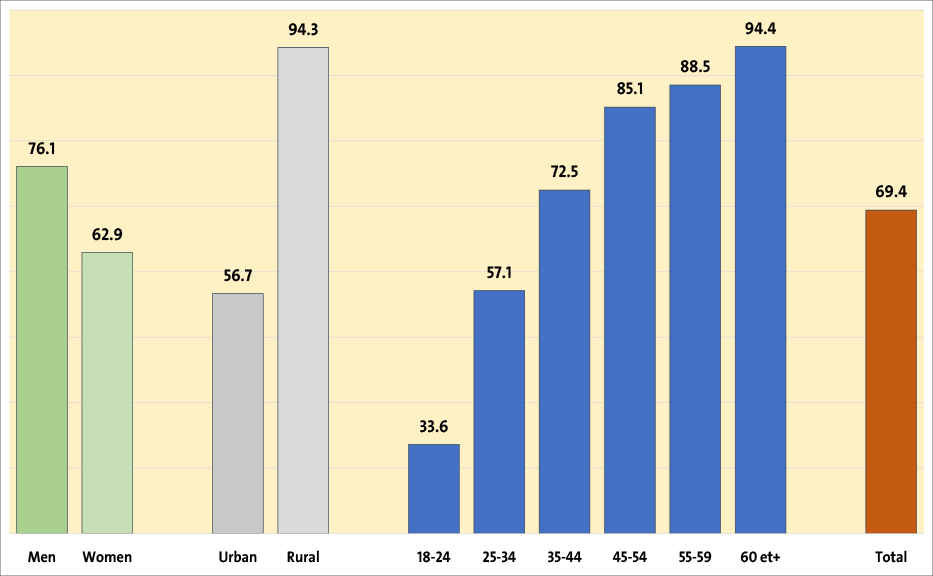

The turnout in these elections reached 17,983,490 voters, an increase of 14.52% from the 2016 elections. Figure 1 shows the percentages of registered voters in electoral lists in terms of age, gender, and distribution between rural and urban areas.

Figure 1: Percentages of those registered in the electoral lists (%)

Source: High Commission for Planning, 7/9/2021, accessed on 12/9/2021, at:

https://bit.ly/2VxVRdq.

2- Legislative Election Nominations

In the legislative elections, a total of 6,815 nominations competed for 395 parliamentary seats (at an average of 17 candidates for each seat), of which 34.2% were women (2,329 nominations). A total of 1704 lists were distributed, including 1567 regional legislative lists and 762 local lists, 97 of which were headed by women.

3- Municipal Election Nominations

Nominations in municipal and county elections amounted to 157,569; Of these, 62,693 lists and 94,776 individual nominations competed for about 32,000 seats (an average of 5 nominations for each seat); Among the nominees, 47,060 were women (29.87%). Nominations for regional elections reached 9,892, of which 3,936 were women (39.79%).[5]

The PJD was only able to cover 26% of the number of nominations. The party attributed this to “pressure” on its candidates to prevent them from running in its name. Many candidates who used to run in the name of the party chose this time to run in the name of other parties, especially the RNI.

The Election Results

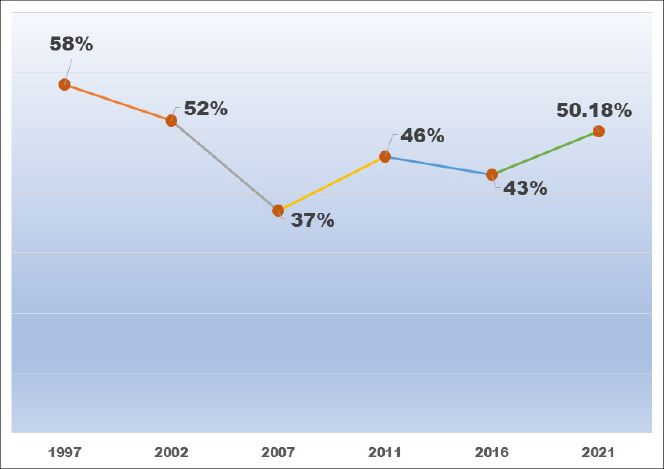

Hours after the ballots were in, the Ministry of Interior announced a turnout of 50.35% compared to 45% in the 2016 elections. This percentage sparked controversy for those who had campaigned for a boycott, who questioned the announced percentage, especially as it increased from 36% at 5 p.m. to 50.35% two hours later. They questioned the practical possibility of about 2 million voters casting their ballots within two hours without long queues outside the polling stations.

Figure 2: Voter Turnout since 1998

Source: Political Studies Unit

The results show that PJD won only four seats in legislative districts, while securing another nine seats thanks to the women quota system (Figure 3). Had it not been for the new electoral divisions,[6] which the party objected to, PJD would not have been able to win any seat in the legislative districts. This is the biggest defeat suffered by a Moroccan political party since independence, especially given that the party won 125 seats in the House of Representatives in the previous elections and dominated all the municipal councils of the major cities in 2015. It is unlikely that the party will chair any municipal council in the coming period, having obtained just 777 out of about 32,000 seats.

Figure 3: Legislative Election Results

Source: ibid.

The elections resulted in the leadership of two parties close to the King: with 102 seats going to RNI, 87 to PAM, 29 to the Popular Movement and 18 to the Constitutional Union. These parties can collectively form the government without the need for party alliances with their political opponents. Meanwhile, the parties of what was known as the “bloc” have made limited progress, as the Istiqlal Party won 81 seats, the Socialist Union of Popular Forces won 34 seats, and the Party of Progress and Socialism won 21 seats. Finally, the radical left was content with the two seats it secured, the first won by the General Secretary of the Unified Socialist Party thanks to the women's quota system, and the second won by the Alliance of the Left Federation candidate. At the local level, the winning parties will form all municipal councils, with slight alliances in some areas between the left and PJD, painting the political scene and all its institutions a single political colour.

Women’s participation in parliament has significantly expanded thanks to the quota system, which helped 90 women secure seats in parliament. A small number of women (3-6) were able to secure a place in parliament without the quota. Youth participation has significantly declined after the abolition of the youth quota system (30 seats), which has been implemented since the 2011 elections and was dispensed with in these elections after facing criticism.

Responses to the Results

The PJD’s defeat led to the resignation of its Secretary-General, with the party issuing a statement that called the election results “incomprehensible and illogical,” and condemned “electoral violations.”[7] There are many factors that led to this defeat, including those related to electoral law changes and royal interference, the role of electoral money, and other issues appealed against by the PJD. But all this cannot hide the fact that a widespread punitive vote took place against the party that has led the government for the past decade. PJD policies regarding contract employment, the abolition of the social support fund, the increase in the retirement age, successive deductions, and the decline in the purchasing power of citizens, especially in the wake of the pandemic induced economic crisis, all created the conditions for blaming the ruling party. The party bears the consequences of policies for which it is not responsible, because it runs the government.

Heading the government without actually ruling is a price the PJD has agreed to pay; forced to pass policies that he does not agree with. During its leadership of the government, there was a decline in respect for human rights, and the electoral base of the party decreased due to the way in which the party’s Secretary-General abandoned its former leader, Abdelilah Benkirane, due to the dissatisfaction of the truly sovereign authorities with him. This deprived the party of a charismatic figure capable of communicating with its supporters. In addition, the party u-turned on many constants that it has traditionally opposed, such as normalization with "Israel" (or approval of it in the government and opposing it in the party), the adoption of the French language in teaching, and the legalization of cannabis. All this alienated the party's base, and led to a resounding defeat. That is why the party lost in these elections with both the authorities and the social base. The loss was greater than expected but not surprising.

The Shape of the Next Government

Two days after the results were announced, the King received the RNI leader, Aziz Akhannouch, and assigned him to form a government based on the provisions of the Moroccan constitution. Although the next government will most likely include the parties favoured by the palace (RNI, PAM MP and UC), while “bloc,” parties will be left in opposition along with PJD and the left, based on the political experience since the 2002 elections, all scenarios remain possible, especially given the diminishing differences between the “bloc” parties and the “administration” parties.

Therefore, the government may consist of the RNI, PAM, MP and UC, and may be joined by Istiqlal or the USFP or even both. The most likely scenario remains the alliance of RNI, PAM and Istiqlal with the addition of complementary parties such as the USFP and MP. The municipal council leadership will mostly go to RNI and PAM, and some councils, especially in southern Morocco, may revert to Istiqlal, while other parties will preside over only a small number of small councils. In addition to presiding over the regional councils, RNI and PAM will completely control the second chamber of Parliament, the House of Councillors.

Conclusion

The September Moroccan 2021 elections have signalled a major change in the political map. The administration parties have come to the political fore, while the power of the Islamist-oriented PJD wanes. But the success of the next government will depend on its ability to meet the expectations of voters, and to fulfil the many party promises made during the election campaigns.

[1] “Akhannouch in Response to Benkirane: The Conclusion is that They Admit the Defeat of Their Party, and What Matters to us Are the Citizens", YouTube, 7/9/2021, accessed on 21/9/2021, at: https://bit.ly/3C8KGHX; "The Fifth Episode of #Election_Studio_Guest, Aziz Akhannouch, Head of RNI", YouTube, 3/9/2021, accessed on 12/9/2021, at:

https://bit.ly/38ZsSST.

[2] Al Adl wal Ihsane association did not organize street marches calling for a boycott, but rather took social media as a platform, and organized seminars in which the radical leftist movement called for a boycott of the elections. For example, see: “Dr. Mutawakkil Describes Blowing up the Participation Rates as 'Scandalous' and Stresses: Ranks in an Entirely Corrupt Process Do Not Mean Anything", Al-Adl and Ihsan Association website, 9/9/2021, accessed on 12/9/2021, at:

http://bit.ly/38WGIWi.

[3] “Democratic Way Report on the 8 September Election Farce,” Democratic Way website, 9/11/2021, accessed on 9/12/2021, at:

https://bit.ly/3BYybhO.

[4] “Morocco: The First Concurrent Elections and 3 Parties Expect Lead,” Anadolu Agency, 8/9/2021, accessed on 12/9/2021, at:

https://bit.ly/38ZZ5JN.

[5] “The Ministry of Interior Announces the Results of the Legislative Elections,” YouTube, 9/9/2021, accessed on 12/9/2021, at:

https://bit.ly/3hpClHR.

[6] “The new amendment stipulates that the number of seats allocated will be based on the “total number of Moroccans eligible to vote” [those subscribed to electoral lists], and not the number of valid ballots. Thus, the denominator becomes much larger [over 15 million out of 38 million], which will diminish the number of seats that parties can obtain in any city. The prospect of substantive change in the electoral results will most likely happen in the upcoming elections. It will be theoretically impossible for any party to gain more than one seat per constituency.” Rania Elghazouli, “Elections in Morocco: Containing Political Islamism with Mathematics,” Friedrich Naumann Foundation, 23/6/2021 accessed on 14/9/2021 at:

https://bit.ly/3A9q4i0.

[7] PJD supporters stage a sit-in in front of Assa-Zag Province Employment Headquarters: “Assa: Citizens protest in front of the Assa-Zag Province Employment Headquarters about the Delay in Announcing the Legislative Election Results,” YouTube, 9/9/2021, accessed on 12/9/2021, At:

https://bit.ly/3C1p00g.