Over the first four months of 2013, Syrian revolutionary fighters achieved some major military successes, most significantly the liberation of the town of al-Raqqah, the defeat of the military campaign against the old city of Homs, and reaching the outskirts of Damascus. As a result of this erosion of the regime’s military control, there was a general sense that it might be possible to tip the balance in favor of the revolution by military means. This impression soon faded when in early April, the Syrian regime initiated a counter-offensive throughout the country. The regime gave immediate priority to three fronts:

The Battle for the Two Ghoutas [agricultural regions outside Damascus]

The regime made military breakthroughs on the Western Ghouta front (Darayya and al-Moadamiya), and reasserted control over the airport highway. In addition, the Eastern Ghouta was put under siege in the Otayba area—the main supply line for the rebels in the area. This led 23 armed brigades in the eastern area to form a joint operations control room on May 12, 2013 and to initiate a battle, given the name al-Furqan, to stem the offensive against the Eastern Ghouta, particularly in Otayba. The rebels were able to eject the regime’s forces from Otayba town, and fighting became concentrated on the outskirts.

The Battle for Maarrat al-Numan

On April 14, 2013, the regime was able to partially break the siege of the military bases at Wadi al-Dayf and al-Hamidiya. The regime also tried to open the Damascus-Aleppo interstate highway, but without success. At the end of April, rebel units forced the regime to retreat from the villages of Babuleen, al-Touh, and Tahtiya toward the town of Khan Shaykhun, the main staging post for the regime’s forces in the countryside to the south of Idlib.

The Battle for Qusair

This began in the first week of April 2012 and remains underway till now. Even though there have been recent breakthroughs by the regime’s forces in the two Ghoutas and Maarrat Numan, they remain incomplete and of limited effect due to on-going skirmishing and tactical withdrawals adopted by both sides. The regime is also aware of the difficulty to achieve a “decisive” resolution on those fronts. For this reason, it has moved to achieve interim goals in terms of reducing the risk to Damascus, in the case of the two Ghoutas, and reducing pressure on the countryside to the south of Aleppo, in the case of Maarat Numan. The battle for Qusair, however, has strategic significance for the regime and the rebels alike, and will have far-reaching implications for the regime and the revolution.

This paper attempts to examine the fighting around the town of Qusair, focusing on its special character and importance in the context of the existing conflict and touching upon its present and future implications for the conflicting parties in the Syrian crisis.

Qusair: A Battle Delayed

Action in Qusair cannot be considered in isolation from the battle for Homs as a whole because the course of events in Qusair has, for more than a year, been tied to events in Homs. Qusair is situated 35 kilometers southwest of Homs and only 15 kilometers from the Lebanese border. The town forms the link between northern Lebanon and the rural region to the south of Homs, and is only around 10 kilometers away from the nexus where most of the Syrian interstate highway network converges. It has a population of 42,000 and forms the administrative center for more than 40 villages. The Qusair region is mixed in terms of religion and sect: Sunni Muslims and Christians are concentrated in the town and its immediate environs (the villages of al-Mouh and Abu Houri) while the surrounding area is comprised of Shiite villages (the largest being al-Burhaniya, al-Sharqiya, al-Aqrabiya, and al-Nizariya) and Alawite villages (al-Haidariya and al-Aboudiya).

Inhabitants of Qusair took part in peaceful protests commencing on April 1, 2011, the Friday of the Martyrs. Protests retained their non-violent character until the end of February 2012, when fighters fleeing Baba Amr took refuge in Qusair. Along with local residents, these fighters formed armed brigades to fight the regime’s army. By the end of March 2012, the town of Qusair was no longer under the military control of the regime, and repeated efforts to retake it were unsuccessful. Despite Qusair’s transformation into the main base for rebel fighters in Homs province after the fall of Baba Amr at the end of February 2012, the regime dropped the town from its list of military priorities during 2012. Their strategy was to strangle the revolution in urban centers and isolate it to outlying rural areas. As a result, all battlegrounds outside Homs were not an urgent priority for the regime at the time.

The course of military operations in Homs province supports the above conclusion. Taking advantage of the joint Russian-Chinese veto of the draft Security Council Resolution proposed by the Arab League on February 4, 2012, the regime launched a major military operation in the Baba Amr district. Over a period of three weeks, the regime succeeded in entering Baba Amr, forcing the withdrawal of armed residents and officers who had defected, and made the district a base in the fight against the regime in Homs.

The regime exploited the capture of Baba Amr in the media and politically. It portrayed the army’s “victory” in Homs as a turning point in the fight to finish off the revolution and thwart the conspiracy orchestrated by global and regional powers. Bashar al-Assad’s visit to Baba Amr on March 27, 2012 should be seen in this context. He announced the return of calm to Homs and instructed the provincial governor to rebuild what had been destroyed in the fighting.

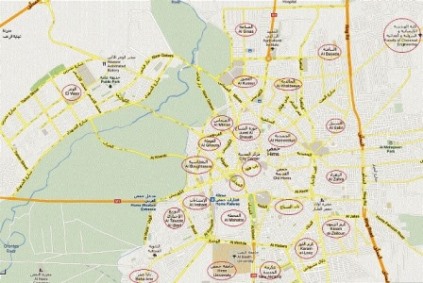

The surprise that the regime had not calculated upon was Syrian Free Army fighters taking up positions in the neighborhoods of the old city of Homs. This led to a renewal of fighting, and, unlike the military operations in Baba Amr, the regime was unable to reassert control over the old city. In mid-June 2012, the regime imposed a siege isolating the old city from the rest of Homs. To complete this isolation, the regime launched a number of military operations during 2012 that aimed at supply lines, particularly in the towns and villages of the countryside to the north (Talbisah and al-Rastan). At the end of 2012, the regime’s army forced its way into the Deir Balbeh district (the gateway to the old city of Homs), and tightened its siege on the other neighborhoods of the old city (al-Bayadah, al-Khaldiya, al-Qusour, al-Qarabis, Jouret al-Shayyah, Bab Hud, Bab al-Dreib, and others). As a result, in early 2013, the Syrian regime began preparations for a military campaign targeting the besieged neighborhoods of the old city of Homs, thereby finishing off the last stronghold of the revolution in Homs (see Map 1).

Map 1: Neighborhoods of Homs

Qusair: Battle Engaged

In early March 2013, and after more than 270 days under siege, the Syrian army announced the beginning of the recapture of the old city of Homs, starting with the Khaldiya neighborhood. However, the expanded military action, which continued for around 10 days, failed to achieve its objectives. The rebels were able to force the regime’s army and the National Defense Force (the sectarian militia formed by the regime) to withdraw from the outskirts of Khaldiya. Additionally, some rebel units that had advanced from the countryside to the south of Homs launched a counterattack on March 10, 2013 in the Baba Amr and al-Inshaat neighborhoods, which they retook until they fell again to the regime’s forces on March 30, 2013. Brigades located in the countryside to the north of Homs (Talbisah and al-Rastan) were able to break through the siege and deliver supplies of food, medicine, and military equipment to the old city of Homs. This enabled the fighters there to remain and continue fighting.

The failure to retake the old city of Homs has had an effect on the regime’s strategy. The siege and isolation of the city did not lead to the desired result of its fall, which meant it needed a change of plan and the adoption of a more active policy. The regime was persuaded that Homs’s weak point lay in its rural hinterland, especially to the south where it runs along the Lebanese border, and where the town of Qusair is of central importance, forming the major supply base for Homs and its peripheral neighborhoods, particularly Baba Amr, Joubar and al-Sultaniya (see Map 2). On this basis, the regime changed its military plans concerning Homs, thereby transforming Qusair from a battle delayed into a battle engaged.

Map 2: Homs Province (Urban and Rural Area)

In numerous confrontations during 2012, the regime witnessed the ferocity of the fighters in Qusair and the military skills arising from their experience and organization. They were also in possession of heavy and light weaponry to match the regime’s forces. This mandated the addition of a new factor to the confrontation: Hezbollah, an expert in guerrilla warfare and a force able to tip the scales. To justify its embroilment in the fighting, Hezbollah’s leadership launched a populist, sectarian mobilization campaign to persuade its supporters of the need for Hezbollah fighters to take part in Syria’s conflict to defend the Shiite villages around Qusair and the religious shrines in the Rif Damascus province, even though no one had attacked the mausoleum of Sayyida Zeinab in Damascus. Such claims themselves are an assault on the Syrian revolution. In a speech on May 1, 2013 Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah admitted that Hezbollah fighters were taking part in the fighting, saying that “the friends of Syria will never permit it to fall into the hands of America, Israel, or the takfiris [extreme jihadis].” In a similar vein, Ali Akbar Velayati, advisor on foreign affairs to Iran’s supreme leader, declared at a press conference in Qom on May 4 that “Syria is not alone. Iran will never abandon it on the battlefield.” Velayati added that “Iran will not play its whole hand in Syria, but will never allow it to fall.” It is thus possible to state that Hezbollah’s participation in the fighting came under Iranian directives and orders.

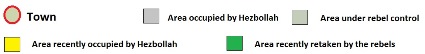

The entry of elite Hezbollah forces into the battle for Qusair tipped the balance in favor of the regime. From mid-April to mid-May 2013, Hezbollah was able to take control of the villages around Qusair to the south and west, including, most importantly, al-Nabi Mandu (Qadesh), al-Burhamiya, and al-Khaldiya, as well as the Josieh border crossing. Hezbollah fighters have also reached the farms around Qusair itself, some two or three kilometers from the town (see Map 3). Simultaneously, regime forces tightened their grip on the village of Abeel (the gateway to the southern countryside in the direction of Homs), and successfully broke the rebel siege of the villages of al-Haidariya, al-Shomaria, and al-Aboudiya on May 8, 2013. The regime then brought in reinforcements from Damascus and deployed them in these villages as the outset of an assault on Qusair. It should be noted that preparations to storm Qusair accelerated after the Lavrov-Kerry meeting on May 6, 2012, which resulted in a US-Russian agreement to hold an international conference in Geneva at the beginning of June, bringing together the regime and the Syrian opposition in an effort to find a political solution to the Syrian crisis based on the Geneva Accords that had been reached by the Contact Group on Syria on June 30, 2012. It would seem that Syria’s regime forces are endeavoring to achieve military gains prior to these talks no matter the cost, and are amplifying the importance of Qusair so as to make any victory seem greater.

Map 3: Deployment of Hezbollah until the Beginning of May 2013

On May 19, 2013, the Syrian Army announced the launching of Operation “Cleanse Qusair” with artillery shelling at 5am, followed by intensive air-raids targeting rebel positions in the rural areas. This led the rebels to pull back to the fringes of Qusair. The regime’s forces then began a ground assault from the north and east of the town, and the 1,200-strong Hezbollah forces from the south and west.

Outcomes and Repercussions

The regime sees the battle for Qusair as crucial and of strategic importance because, from its perspective, it will reshuffle the cards of the conflict inside Syria, as well as regionally and internationally. The most important likely outcomes and repercussions are as follows:

The regime succeeds in winning the battle for Qusair, which will enable it to enforce the siege on the old city of Homs by cutting off supply lines entirely, a prelude to storming the city to regain control. This would mean the isolation of the revolution in regions far from the center (the north, the far south, and the east). The regime would then have everything needed to survive and endure in that, for the first time since the mid-2012, it would have ensured secure territorial continuity of the area between the capital and the central region (Homs and Hama), extending to the Syrian coast, which is considered the safest and most stable region in Syria. It should be noted that throughout 2012 the Syrian regime undertook the revamping of strategic infrastructural facilities in the coastal provinces (Tartous airport and the ports), and offered economic incentives to industrialists and investors from Aleppo and the Damascus region to transfer their businesses to the secure areas on the coast.

The regime succeeds in redeploying its forces geographically as outlined above. This will strengthen its negotiating position should the anticipated political track for a solution to the crisis open up (the international conference), and provide its international and regional allies with greater ability to impose their positions and conditions. With this as a starting point, it is possible to state that the battle for Qusair represents an expression of international and regional will to change the course of events on the ground, and is not solely the choice of the regime alone.

The battle for Qusair has clearly exposed Hezbollah’s penetration into the Syrian crisis and its direct military involvement. Whether willingly or by compulsion, Hezbollah has been drawn into a battle where it is fighting alongside a dictatorial regime and justifying this on sectarian pretexts. This has affected Hezbollah’s image, and, has affectively, at least for broad swathes of Syrians and Arabs, changed it from a resistance movement confronting Israel and backed by the Arab public into a dubious and aggressive sectarian party, totally and absolutely bound to Iranian political and ideological directives. The involvement of Hezbollah has helped fan sectarian polarization in Syria, and added a religious, confessional dimension to the conflict. In addition, Hezbollah’s direct involvement in Syrian battles will lead to the erosion of its military and human resources, thereby achieving Israel and the US’s current objective of turning Syria into a space where “the forces of extremism,” that is the Islamist movements and Hezbollah, can fight it out.

Since the battle for Aleppo, it has been maintained that in Syria there can be no decisive battle, or “mother of battles” as it is put, for the Syrian revolution extends vertically and horizontally within Syrian society.

If the regime is able to regain control of Qusair in the near future, this will have major implications for the revolution, in terms of morale and military. It will not, however, define its fate as is being widely suggested. The struggle with dictatorship is not measured according to the balance of forces, nor according to advances or defeats in a specific arena. Equally, any success achieved by the regime by means of massacre and slaughter only confirms the necessity and legitimacy of the revolution, and that it must continue.

The potential risks to Qusair, in particular, and Homs more generally, could create an opportunity for the rebels to look beyond their divisions and fragmentation in Homs and Syria as a whole. They might be pushed into forming regional command structures, possibly extending to the national level, able to organize military action deemed necessary now and in the future for the revolution to succeed. Up to the time of writing, the rebels were still putting up surprisingly stiff resistance to the attacking forces, which might upset the calculations at any moment. The most important thing is for the revolution to recognize the danger inherent in the absence of a unified, hierarchical command structure and the necessity to move as a single body at the same moment.

*This Assessment was translated by the ACRPS Translation and English Editing Department. The original Arabic version published on December 4th, 2013 can be found here.