Water is not only the primary source to sustain life, but it also plays an important role in various aspects of human life. Water has a great significance in Iranian culture and has been a source of inspiration, strength, and cooperation and social integration among communities. Historical explorations reveal that Iranian people have invented a variety of methods and techniques to meet their water demands. It is not possible to define a single method of water management across a country with such a vast and uneven territory of various morphological, environmental and climatic regions. Geographic and climatic variations, as well as different types of available water resources, have resulted in different methods of exploitation and use in different parts of Iran. (Figure 1)

In hot arid areas, people invented the

qanat, a type of underground drainage that uses gravitational force to bring water from the level of an aquifer to the surface of the earth.

Abanbars are another water management technique that is employed in central part of Iran.

Abanbars are roofed underground water cisterns that store water from the permanent sources of springs and qanats or the surface runoff resulting from precipitation to supply water for the communities. People living in the northern strip of the country, meanwhile, enjoy abundant rainfall and built cisterns to collect and use water for various domestic and agricultural purposes.

Figure 1. Fit-for-purpose solutions of traditional (top) and one-size-fits-all solution of current (bottom) urban water management system.

With the expansion of the modern urban water networks some 70 years ago, various traditional practices of urban water management lost their popularity and were abandoned. Unlike many traditional water management practices, which were adapted to the environment and fitted into nature, current urban water pipe networks as “technology-oriented” solutions lack local characteristics. The modern urban water network is based on long-distance transfer to manage urban water using recent technologies. Similar networks are implemented across various climatic conditions as a one-size-fits-all solution. Demographic changes, technological advancements and sanitation concerns, among other issues, have accelerated the shift to an underground urban water pipe network. In the modern city, water became a commodity to serve the population and its otherwise aesthetic, social and environmental benefits in the urban setting were highly neglected.

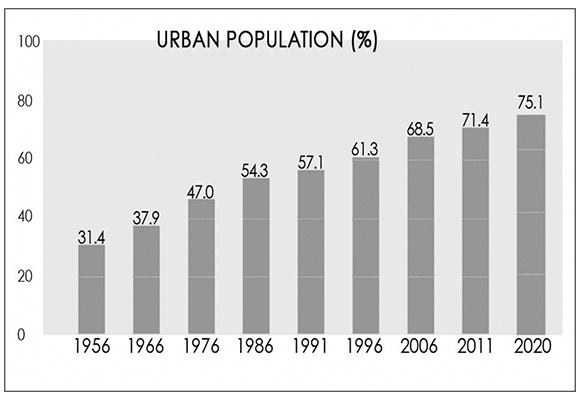

The Iranian population has increased approximately six times over in the last century, with major population growth occurring in the 1960s and afterwards. Such a rapidly growing population has imposed growing demand on Iran’s water resources. The situation in Iran, which is classified as a semi-arid country with limited water resources and little annual precipitation, is very problematic. (Figure 2) Moreover, Iran has experienced rapid urbanization, with the country’s urban population increasing from 30 percent to 75 percent between 1960 and 2020.[1] The rapid expansion of cities and a rising urban population have meant improvements in living standards for a larger population and, as a result, increased domestic use of water, particularly for hygiene purposes. Increased water consumption has reduced per capita renewable freshwater availability and put additional strain on the country’s natural water cycles. A study shows that despite limited water availability, Iran’s water consumption is twice the global average, and to meet such high demand, Iranians are currently using more than 70 percent of their renewable freshwater resources.[2]

Figure 2. Urban population growth of Iran in the last 65 years

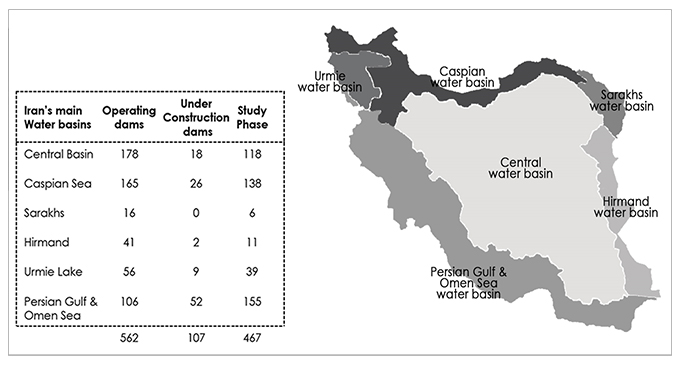

To respond to the increasing water demands, cities have had to increase the supply of water to population centres. Since many urban centres are not located close to the sources, the conventional option has been to rely on long-distance pipelines and tunnels. To facilitate these water transmission projects, many large reservoir dams have been constructed. (Figure 3) Moreover, new technologies have allowed people to dig deep wells and extract water for their domestic and agricultural purposes. This uncontrolled water extraction from underground water puts so much pressure on Iran’s groundwater resources and dramatically altered the hydrological balance in various water basins of the country. The widespread introduction of diesel-engine and electric-motor pumps all over Iran, even in the small and remote villages, has accelerated the shift away from traditional water supply techniques and increased water exploitation. Other weaknesses of traditional water infrastructure include sanitation concerns and maintenance difficulties, which result in less efficiency and acceptance of such practices, as well as further development of the centralized network of the urban water system in different Iranian cities.

Figure 3. Iran’s dam construction projects in main water basins facilitated inter-basin water transfer as a response to water scarcity (http://daminfo.wrm.ir/fa/dam)

The reality of Iran’s urban water management system is that after nearly 70 years of extensive infrastructure building programs, water supply projects now cover more than 98 percent of urban areas and nearly 67.5 percent of rural areas. But while the current urban water network is successful in meeting the primary goal of safe water delivery and distribution and waste and stormwater collection and management, it has fundamental flaws such as poor environmental performance, lack of resilience, and a diminished social and aesthetic significance of water in urban areas. Such deficiencies are the primary motivators for a paradigm shift in the water management infrastructure of Iranian cities. The following table presents some of the causes, effects and potential threats to the current urban water infrastructure of Iranian cities. (Table 1)

Table 1. Water problematics of Iran

|

Geographical and climatic conditions | Limits on available water resources | Water scarcity |

Growing population

and rapid urbanization | Increased water consumption | Water shortage |

|

Lack of social and cultural significance of water in cities | Less appreciation of water growing consumerist culture | Water shortage Pollution of water resources |

|

Climate change | Extreme weather events | Drought Flooding

|

Although traditional practices cannot respond to the current and ever-increasing demand of Iranian society, studying these practices and identifying their characteristics can lead us to define a new, sustainable, resilient model of urban water infrastructure. Building a bridge between the locally adapted practices of the past and the new advancements in urban water infrastructure may be the key to the new urban water management system. To this end, the next section explains some of the characteristics of the traditional water management system, which can be employed to define the new sustainable urban water management system of Iranian cities.

Climate-Responsive and Nature-Oriented

Traditionally, people have inhabited places with ready access to freshwater and developed various water management techniques based on locally available sources of water. The current paradigm of urban water management, on the other hand, is based on long-distance, subsurface transfer of water. As a result, the geographic distribution of Iran’s population is not consistent with the geographic distribution of its water resources. Currently, about 26 percent of the total population is concentrated in the ten largest cities. This ultra-concentration of the population in a handful of locations has resulted in the development of extensive infrastructure allowing for more water transfer in and between basins. These long-distance central networks require a huge amount of energy and thus drive carbon emissions – unlike traditional techniques, which are energy-neutral. The current urban water infrastructure may temporarily solve the problem of water shortage in urban areas, but it does not address the main cause of the problem and thus, fails to prevent environmental catastrophes. One example of such a crisis management approach in facing the water shortage of central Iran is transferring Caspian Sea water over 185 kilometers from north to Semnan Province, in central Iran.

The multidimensional role of water infrastructure to the city

Traditional water management techniques created social nodes within the urban structure. In contrast with the invisibility of the current infrastructure, traditional techniques had a strong presence as social amenities of the community. For instance, the Abanbar – as the source of clean water for people, along with the other public facilities such as the mosque, school and public bath – was one of the main landmarks of old neighborhoods, generally located on the central square (meydan). The same principle applied to the outlets of qanats and farming ponds as well as other water management techniques in various urban settings.

A farm pond is a rainwater harvesting technique that is mainly practised on the larger scale of the cities and villages to collect rainwater for agricultural purposes. The same technique has been used in different regions of the country under various names: known as

Gal in Eastern Azerbaijan Province,

Bandsar in Khorasan Province,

Esel in Lorestan Province,

Hutak in Sistan and Baluchistan Province, and

Sal in Guilan Province. Although all are designed to serve the same function, the form, size and building methods used vary from one region to another. The rain and stormwater running from the upper or neighbouring catchments are collected and directed into these small reservoirs and used in the cultivation period. Historical investigations reveal that almost all the cities and villages in Guilan province had one or more ponds to provide water for various uses such as agriculture, fishing and other recreational activities. Apart from their original functions, farming ponds have contributed to the quality of spaces in different ways. The still water of the pond, combined with the surrounding greenery in the villages and cities, was an important element in defining the rural landscape. The pond, as a large body of water within the built environment, contributed to the aesthetic qualities and visual attractiveness of the city. Furthermore, it was a generative location for bringing people together for various recreational and leisure activities such as fishing, swimming, picnicking and alike.

The invisibility of the underground water pipe network has weakened the architectural and aesthetic significance of water in cities. Moreover, water features such as fountains, streams, and ponds have lost their function in supplying or distributing water and are now merely ornamental. Currently, the diversity of water features is mainly due to the existence of fountains and water sculptures to decorate urban squares and parks, and the presence of water bodies such as lakes and pools in urban parks and recreational spaces. Studying the early examples of the use of water in public spaces and place-making processes reveals that there is no conflict between the aesthetic values of a design attempt, which are outcomes of decoration and ornaments, and practical matters such as function, use, cost and local economy. On the contrary, it is repeatedly argued that decoration and ornaments can contribute to the better function of a given space in various ways.

The urban water management of the future should embrace all various aspects of design with water to maximize the benefits that such a vital element can offer to our cities. After a long period of neglecting water in public spaces, urban water management should change to recall the beauty and grace that water can bring to our spaces, while using its various capacities to create a pleasing and well-functioning space – and to provide comfort in a warming globe, while making the most use of the limited amount of water through reducing, recycling and reusing already used waters.

Community-based practices vs. large-scale governmental projects

The traditional water management techniques of various parts of Iran were products of sustainable cycles. People residing in each region of the country inherited these techniques from their descendants and transferred the knowledge to the next generations. Many of these techniques and traditions have been further developed by newer generations over time. Such local practices of water management in each climatic region had produced a particular interaction between man and the water resources. Being dependent on local sources of water, the water infrastructure needed constant work to maintain, work which could only be guaranteed by the cooperation of the local groups and active participation of the members of each community in their water resource management. Hence, communities were responsible not only for building and maintaining their water infrastructure, but also for managing and distributing available water among the people. In Iran, these have conditioned the social structure of communities that established their rights of property, use, and division of water in regard to the different types of sources long before the development of Islamic civilization. Later, after the coming of Islam, these verbal traditions and modern principles were synthesized into a body of law regulating the management of community water resources. A veritable army of maintenance and construction workers, measurement experts, registry and tax agents and dispute mediators guaranteed state control.

Despite the long history of local use and management of water resources, the advent of the modern urban pipe network in the second half of the twentieth century brought about a paradigm shift away from traditional, bottom-up water management systems (harvesting, storing etc). As cities grew and needed more water, communities searched for modern facilities to provide fast and easy access to water, and thus replaced community-based practices and techniques with large-scale regional and national urban water infrastructure. Correspondingly, with the development of large-scale infrastructure, the government’s role in the implementation and operation of projects on water security, water supply for cities, irrigation, and drainage networks increased. As a result of lower rates of local participation in current water resource management, the local knowledge accumulated over centuries and transmitted through the generations is on the verge of being lost. Even though the vast majority of urban Iranians today enjoy constant access to freshwater, and urban water consumption per capita has enormously increased in the last few decades, people are not familiar with the journey of water from its source to their kitchens and bathrooms.

The Necessity of Paradigm Shift in Urban Water Management

The current paradigm of urban water management in Iran is based on economic targets, and to a great extent lacks environmental, social and aesthetic considerations. The urban water management of Iranian cities should change to go beyond its primary function of managing water supply, wastewater and stormwater of the city, and embrace other environmental, aesthetic, social and economic objectives to bring multiple benefits to the city and its citizens. Such a water management system will respond to the water demands of the community, become a place-making feature in the urban environment, enhance the visual quality of the city, and reduce environmental impacts. Finally, it should improve resilience to future climate changes.

[1] Data collected from the Statistical Center of Iran.

[2] Kaveh Madani, “Water Management in Iran: What is Causing the Looming Crisis?”

Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 4, no.1, (2014): 315-328.