Housing can have a significant impact on the welfare of households by addressing their immediate residential needs, affecting their health as well as access to various social services, and satisfying their future financial needs as a major asset. Furthermore, the housing sector is an important generator of jobs and its price inflation can affect the macroeconomy in significant ways. Given its considerable wealth aspect, the real estate market associated with housing can become an important arena for speculative and hoarding activities, as well as a source of enormous inequality. In the mid-1970s, such circumstances became a major cause of discontent in Iran and arguably influenced the events leading to the country’s 1979 Revolution. The Islamic Republic’s Constitution thus places a strong emphasis on housing rights: “Every Iranian individual and family has the right to have a dwelling that meets their needs. The government is required to provide the means for the execution of this principle by giving priority to those who are in greater need, especially peasants and workers (Article 31).”[1] Over the last four decades, a number of initiatives and pieces of legislation have been enacted in pursuit of this goal, with those actually coming to fruition largely focusing on homeownership. Despite this, housing affordability—for purchase or rent—and homeownership rates in Iran’s urban areas have continued to decline, while informal settlements have expanded on the outskirts. As a result, housing remains a major issue in the country, as suggested by some of the lofty promises made during presidential debates in 2021 presidential elections. This case analysis highlights Iran’s major housing policies and their outcomes since 1979 along with the challenges that the country's new government administration will face in the near future.[2]

Early Post-Revolutionary Housing Initiatives

During the first post-revolutionary decade, several pieces of legislation were adopted to restrict land and housing tenure, facilitate takeover of land by the government, and allow for the distribution of urban land to those in need of housing. The government further strove to provide subsidized home mortgage loans and construction materials, carry out a large number of sites-and-services projects, and promote the formation of housing cooperatives. New institutions were also established to provide housing for disadvantaged groups, the most important of which was the Housing Foundation of the Islamic Revolution.[3] Despite their lack of long-term strategy and haphazard manner of implementation, these efforts succeeded in reducing land prices, controlling home and rental prices, decreasing the share of housing in total household expenditures, and temporarily restraining property speculation.[4] However, they also provided incentives for rural-urban migration, larger families, and urban sprawl as well as disincentives for the proper development of the housing sector.

The post-Iran-Iraq-war First National Development Plan (for the period 1989-1993)[5] had a relatively disappointing performance in the housing sector. Supply of housing for blue-collar workers and government employees as well as rental units faced serious hurdles; provision of infrastructure for sites-and-services projects proved challenging; prices began to increase rapidly despite large government investments and land allocations; and both real estate speculation and informal settlements proliferated.[6] The Second and Third National Development Plans (for the periods 1995-1999 and 2000-2004 respectively) focused on supporting mass production of homes by carrying out sites-and-services projects, providing incentives (especially subsidies) to builders, subsidizing a saving and mortgage loan fund at the Housing Bank, and supporting homeownership for various types of public-sector employees.[7] The plans included initiatives for the rental market (in reality rent-to-own schemes) and for low-income groups. Targets for neither were realized in any significant way. Yet, removing land-market restrictions and reducing subsidized land allocations, which would end altogether by the end of the Third Plan, gave rise to speculative activities and rapidly increasing prices in the housing sector. These circumstances were exacerbated by growing sales of construction rights for higher floor area ratios in major urban areas, a growing inclination of public-sector agencies to make profits from land and housing sales, reduced subsidies provided to the housing sector, and rising mortgage rates and shrinking access to housing finance. There was thus an obvious need for a multi-pronged approach to address the growing housing conundrum.

Comprehensive Housing Plan and Mehr Housing Plan

The Fourth National Development Plan (2005-2009), formulated toward the end of President Khatami’s tenure, had a strong focus on housing for low-income households. It called for the preparation of a Comprehensive Housing Plan (CHP).[8] The CHP was supposed to streamline housing subsidies under a comprehensive social policy framework, reform urban planning and land management structure to address the needs of low-income households, overhaul the housing finance system, and decentralize housing initiatives.[9] These goals were largely abandoned once Ahmadinejad took office as president. But the new administration did leverage certain provisions of the CHP to create a housing mega-project called Mehr Housing (MHP).

The MHP, launched in 2007, envisaged construction of 1.5 million (subsequently revised to 2.3 million) low-income housing units across the country.[10] The program entailed providing free public land, subsidized finance, and tax exemptions/discounts. MHP units were supposed to be constructed quickly within a few years. Eligible applicants were to pay around one third of the price of their units upfront in installments. They would then receive a long-term low-interest loan from the Housing Bank to address the rest of the cost of their units.[11] Although many of the units were handed over to customers by the mid-2010s, some MHP activities continued to take place during the Fifth and the first part of the Sixth Development Plans (that is, as late as 2019). Around 2.2 MHP units were built by 2017, on both government-supplied land and self-owned land.[12] MHP activities faced capacity and financing challenges. Budget shortfalls had inflationary consequences which affected low-income groups disproportionately and increased the cost of MHP units. Many of the housing units were constructed in remote areas lacking infrastructure, while those located in the new towns put extra pressure on the existing infrastructure and services. Increasing costs along with remote locations without immediate access to services and jobs made many of the units unaffordable or unattractive to low-income groups. A large number of units would be rented out rather than occupied by their supposed low-income owners, while some informal settlements appeared right next to certain MHP sites. These developments reflected a mismatch between MHP and the requirements and means of most low-income households. To be fair, MHP has had an element of success in securing homeownership for a large number of beneficiaries, while in many instances, the provision of infrastructure and services in MHP sites have improved over time.

Recent Housing Policies

While the Rouhani administration has criticized the MHP and called for the revival of the CHP including its social housing provisions,[13] it has also committed to completing the MHP activities. The Revised Comprehensive Housing Plan (RCHP)[14] was drafted by the Ministry of Roads and Urban Development to address the rising share of housing in total household expenditures, rapidly increasing land costs, grossly inadequate supply of affordable housing in the formal sector, and the expansion of informal settlements. Some of its important proposals included establishing a housing fund, making mortgage finance available to low-income households and slum dwellers, institutionalizing a social housing program, and supporting a rental housing program targeting low-income households. A related document was drafted in 2017 by the government containing initiatives on social housing and supported housing, which included provisions for rent subsidies and construction of rental units. This was apparently put forward as a replacement for MHP to construct 100,000 low-income housing units within five years (half of what was envisaged in RCHP). The Sixth National Development Plan (2016-2021) further supports such initiatives, while it calls for rebuilding the housing stock in slum areas as part of regeneration activities as well as providing inexpensive finance and land for the construction or purchase of homes aimed at low-income groups.[15]

These social and low-income housing plans have not been implemented, seemingly due to their implementation and funding difficulties. Instead, the government has adopted a limited initiative since 2019 resembling the MHP, the National Housing Production Action Plan (NHPAP), aimed at constructing 400,000 homes by 2022 across the country.[16] While some of these planned homes are intended for low-income households, their volume and price tag are unlikely to succeed in addressing Iran’s housing woes any more than the MHP did. Of note is that several welfare organizations in Iran (including the State Welfare Organization and revolutionary charity institutions) currently maintain some housing assistance schemes aimed at vulnerable groups. Their most important beneficiaries are families with disabled members as well as disadvantaged female-headed households. Yet, their activities have remained quite limited, given the large population actually needing housing assistance.

Housing Trends

As shown in Table 1, the homeownership rate in Iran has continued to decrease over the last two decades—from 77 percent in 1991-1992 to 64.8 percent in 2018-2019. In the same period, the average share of housing costs in total household expenditures rose from 26 to 36 percent. Low-income households have been affected more severely by these developments. As a result, the percentage of households falling under the housing poverty line has been increasing—for example from 24 to 31 percent between 1996-1997 and 2013-2014.

Table 1: Trends in Homeownership, Share of Housing in Household Expenditures, and Housing Poverty

| Homeownership rate (percent) | 77 | 74 | 71.5 | 66.6 | 63.5 |

| Average share of housing in household expenditure (percent) | 26 | 27 | 28

| 34 | 36 |

Households under housing poverty line (percent of all households)

| - | 24 | - | 31 | -

|

Source: Alaedini, P. & Yazdani, F. (2021, forthcoming). Iran's Housing Policies for Low-income and Vulnerable Groups: A Critical Assessment. In P. Alaedini (ed.),

Social Policy in Iran: Main Components and Institutions, Routledge (based on figures from the Statistical Center of Iran's household expenditure-income surveys and background studies for the Comprehensive Housing Plan).

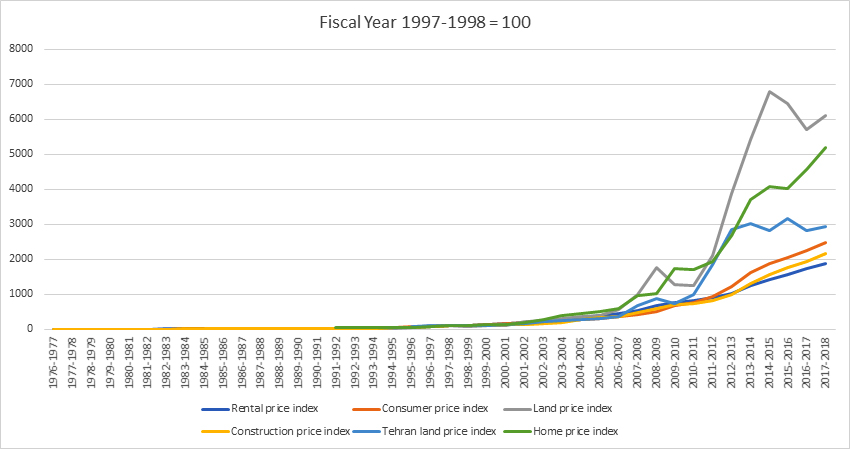

Figure 1 shows trends in the urban land price index, Tehran land price index, home price index, rental housing price index, construction price index, and consumer price index over a forty-year period. Land and housing prices have increased more than 100-fold since the early 1990s, that is, much faster than the consumer price index. Thus, while lower income groups have been severely affected by high inflation rates, they have been hit even harder by rising real estate prices. Many of them have lost out on the significant housing wealth that has accrued to households enjoying homeownership. Although rental prices have moved in line with the rate of inflation, their rapid rise has been highly disruptive of the lives of renters by pushing many of them to lower-price areas. Rising housing costs and reduced housing affordability has fueled the proliferation of urban informal settlements. Background documents for the Sixth Development Plan give a figure of 3.2 million households or nearly 12 million persons for the population of informal settlements living in 25-30 percent of the urban housing stock.[17]

Figure 1: Land, Home, Rental, Construction, and Consumer Price Indexes—1976-2017

Source: Alaedini, P. & Yazdani, F. (2021, forthcoming). Iran’s Housing Policies for Low-income and Vulnerable Groups: A Critical Assessment. In P. Alaedini (ed.),

Social Policy in Iran: Main Components and Institutions, Routledge (based on figures from the Central Bank of Iran’s time series data).

Housing Policy Challenges

A number of initiatives have been tried by successive Iranian government administrations over the years in the housing sector—including subsidized supply of land, construction materials, energy, and finance, tax exemptions and discounts, and, on a much smaller scale, public and rent-to-own housing as well as supported housing for vulnerable groups. These activities have had some achievements but have not been able to address the growing housing woes since they have lacked comprehensiveness and inclusiveness as well as sustainability. Twice in the past, Iran’s government administrations have failed to implement multi-pronged and comprehensive housing programs they have formulated. The emphasis has instead been placed on large-scale homeownership initiatives, which have a more populist appeal, are relatively simple and quick to implement, and can be more lucrative for some stakeholders. This focus has ignored the diverse demands associated with low-income households and various social groups. Government activities have also failed to give adequate attention to the need for connecting housing with poverty-reduction and social welfare programs.

The new government administration taking office in 2021 in Iran should seriously consider readopting the Comprehensive Housing Plan, which provides a good blueprint for a multipronged strategy in the housing sector. Nonetheless, the existing draft document lacks details in many areas, which must be addressed through careful planning and capacity building. There is a need to especially focus on social, low-income, and rental housing parts of the existing framework by further leveraging international best practices and innovative local solutions. There is significant room for government action to address failures in the real estate, housing, and mortgage finance markets. Until now, there has been little systematic approach to housing subsidies, which have been provided by multiple public-sector actors with different and often contradictory agendas. They have hardly reached the lowest income strata, who have been forced to find shelter in the country’s expanding informal settlements. The housing subsidy system and its targeting mechanism must be reformed to become inclusive of the poor. Of equal importance is to tackle the adverse manifestations of Iran’s political economy in the housing and real estate markets: property speculation, property hoarding, land grabbing, and rising real estate prices at the expense of low-income groups in terms of both access to housing and widening wealth inequalities. This requires devising effective property tax and land management systems at a minimum.

[1] English translation of the Islamic Republic Constitution available at the website of the World Intellectual Property Organization (https://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/ir/ir001en.pdf).

[2] This case analysis draws from the research conducted for the following book chapter: Alaedini, P. & Yazdani, F. (2021, forthcoming). Iran’s Housing Policies for Low-income and Vulnerable Groups: A Critical Assessment. In P. Alaedini (ed.),

Social Policy in Iran: Main Components and Institutions, Routledge.

[3] This foundation has mostly focused on rural housing over the past four decades despite its original broader mandate.

[4]Abdi, M. A., Mehdizadegan, S., & Kordi, F. (2011).

Shesh daheh barnameh-rizi-ye maskan dar Iran—1327-1387 [Six decades of housing planning in Iran—1948-2008], Tehran: Building and Housing Research Center, Ministry of Housing and Urban Development.

[5] Texts of Iran’s five-year economic, social, and cultural plans and their background documents are available at the Plan and Budget Organization’s macroeconomic affairs website (https://mpb.mporg.ir/Portal/View/Page.aspx?PageId=509471ce-ff70-4609-9f78-8d172089ee2f).

[6]Abdi, M. A., Mehdizadegan, S., & Kordi, F. (2011).

Shesh daheh barnameh-rizi-ye maskan dar Iran—1327-1387 [Six decades of housing planning in Iran—1948-2008], Tehran: Building and Housing Research Center, Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, pp. 125-140.

[7]Ibid, pp. 163-165.

[8] Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (2006). Comprehensive housing plan—Analytical document (research summary) and strategic-implementation document.

[9] Yazdani, F. (2015), Tarh-e jame’-e maskan, asibshenasi-ye sakhtari va ruykardha-ye rahbordi [Comprehensive housing plan, analysis of structural problems, and strategic approaches].

Faslnameh-ye Elmi-ye Eqtesad-e Maskan, (51):35-56.

[10]Majles Research Center (2017). Barrasi amalkard-e vezarat-e rah va shahrsazi dar dowlat-e yazdahom: b. bakhsh-e maskan va shahrsazai [Assessing performance of Ministry of Roads and Urban Development during the 11th government administration: b. housing and urban development sector]. Office for Infrastructure Studies, No. 15506. https://rc.majlis.ir/fa/report/show/1031314

[11] Alaedini, P., & Fardanesh, F. (2014).

From shelter to regeneration: Slum upgrading and housing policies in Islamic Republic of Iran. Tehran: Urban Development and Revitalization Organization, pp. 53-54.

[12]Majles Research Center (2017). Barrasi amalkard-e vezarat-e rah va shahrsazi dar dowlat-e yazdahom: b. bakhsh-e maskan va shahrsazai [Assessing performance of Ministry of Roads and Urban Development during the 11th government administration: b. housing and urban development sector]. Office for Infrastructure Studies, No. 15506. https://rc.majlis.ir/fa/report/show/1031314

[13] Majles Research Center (2013). Akhudi tarh-e maskan ejtamai ra in hafteh be majles mibarad [Akhundi will take the social housing plan to the Majles this week]. https://rc.majlis.ir/fa/news/show/864365

[14] Ministry of Roads and Urban Development (2015). [Revised] comprehensive housing plan (2015-2026)—Integrated document.

[15] Management and Planning Organization (2015). Detailed document of the Sixth Economic, Social, and Cultural Plan—Sectors, vol. 1, pp. 154-162. https://mpb.mporg.ir/Portal/View/Page.aspx?PageId=99895250-daf0-49f4-a46b-78ac3369d

[16] Ministry of Roads and Urban Development (2019). Barnameh-ye eqdam-e melli-ye maskan [National action plan on housing production].

[17] Management and Planning Organization (2015). Detailed document of the Sixth Economic, Social, and Cultural Plan—Sectors, vol. 1, pp. 167-169. https://mpb.mporg.ir/Portal/View/Page.aspx?PageId=99895250-daf0-49f4-a46b-78ac3369d