Syria-Israel negotiations accelerated markedly in the run up to the 80th session of the UN General Assembly scheduled to begin 23 September, with considerable pressure exerted by the US envoy to Syria, Tom Barak, to reach an agreement in advance. Syrian President Ahmad al-Sharaa indicated the possibility of signing an agreement with Israel during his stay in the United States, stating: “We are very close to reaching an agreement with Israel under US mediation.”

[1] Despite stressing that “the agreement with Israel will be similar to the 1974 Disengagement Agreement and does not imply normalization of relations or Syria’s accession to the Abraham Accords,” the Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that the agreement, expected to be signed this September, is part of “a series of successive agreements” that will be concluded with the Israeli side before the end of 2025.[2]

Syria-Israel negotiations accelerated markedly in the run up to the 80th session of the UN General Assembly scheduled to begin 23 September, with considerable pressure exerted by the US envoy to Syria, Tom Barak, to reach an agreement in advance. Syrian President Ahmad al-Sharaa indicated the possibility of signing an agreement with Israel during his stay in the United States, stating: “We are very close to reaching an agreement with Israel under US mediation.”

[1] Despite stressing that “the agreement with Israel will be similar to the 1974 Disengagement Agreement and does not imply normalization of relations or Syria’s accession to the Abraham Accords,” the Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that the agreement, expected to be signed this September, is part of “a series of successive agreements” that will be concluded with the Israeli side before the end of 2025.[2]

Negotiations Under Fire

Following the collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime on 8 December 2024, the Syria-Israel front underwent profound military and security transformations. The Netanyahu government capitalized on the disintegration of the Syrian army to declare “the agreement void until order is restored in Syria.”[3] Israel subsequently advanced into and occupied the demilitarized zone in the Golan Heights (235 square kilometres) that had been established under the agreement. It further expanded its control and incursions into Syrian territory, in a total area of nearly 600 square kilometres. Concurrently, Israel launched a large-scale aerial campaign that destroyed the bulk of the Syrian army’s weapons and equipment. In July 2025, Israeli airstrikes penetrated the vicinity of the presidential palace in Damascus, amid events unfolding in al-Suwayda. Within this context, the Trump administration initiated direct negotiations between Israel and Syria, alternating between Baku, Paris, and London, with the aim of eventually incorporating Syria into the “Abraham Accords” launched during Trump’s first term (2017-2021).

During his meeting with al-Sharaa in Riyadh on 14 May of the same year, Trump extended an invitation to Syria to join the normalization process with Israel, pledging in return to lift the sanctions imposed on the country.

[4] Washington clearly linked progress in negotiations with Israel with the lifting of sanctions on Syria.[5] This was made evident by the activities of Syrian Foreign Minister Asaad al-Shaibani, who travelled to Washington to discuss the issue of sanctions relief following talks in London with Israel’s Minister of Strategic Affairs, Ron Dermer. Those talks, attended by US Special Envoy to Syria Tom Barrack, centred on a draft security agreement proposed by Israel.[6] These discussions had been preceded by negotiations in Paris, which focused on de-escalation measures as well as on monitoring the ceasefire in al-Suwayda – an arrangement reached under US mediation in July 2025 that also entailed the reactivation of the 1974 Agreement. Despite official statements describing the forthcoming agreements as “security agreements,” the negotiations were not conducted between military officials but rather between high-ranking political figures in direct meetings.

Contours of the Prospective Security Agreement between Syria and Israel

President al-Sharaa’s administration is seeking to revive the 1974 Disengagement Agreement, while showing readiness to accept certain amendments (“1974 Plus”). Israel, in contrast, seeks to impose a new agreement, capitalizing on Syria’s current vulnerability and the inability of its new government to forge a national consensus that would safeguard the unity and stability of the country. On this basis, Israel presented Syria with a detailed proposal for a new security agreement concerning the southwest of the country, ahead of the meeting between Dermer and al-Shaibani in London on 17 September.[7]

The full details of the agreement have not yet been disclosed, but according to media reports its core rests on Israeli commitments to gradually withdraw its forces to the lines of the 1974 Disengagement Agreement,[8] with the exception of two forward positions on Mount Hermon,[9] while deferring the question of the status of the Golan Heights. For its part, Syria would pledge to prevent its territory from being used for attacks against Israel, while Israel would undertake not to interfere in Syria’s internal affairs and to recognize the government of Ahmad al-Sharaa. The latter stipulation is peculiar, for it requires Syria to secure recognition of its government by an enemy state that continues to occupy Syrian land.

The arrangements further envisage dividing southern Syria into three zones, modelled on the Camp David Agreement with Egypt (though in contrast, Egypt recovered the entirety of its occupied territory, the Sinai). Each zone would be subject to specific restrictions on the types of forces and weaponry permitted, prohibiting military presence or heavy armaments in the demilitarized area and allowing only police and internal security forces. This was the arrangement to which Egypt consented in Sinai, and one that Syria had previously negotiated for the Golan – i.e. for land restored to Syrian sovereignty – balanced by parallel demilitarized areas on the Israeli side. Imposing such a plan south of Damascus, however, would effectively transfer the basis of the Golan arrangements to these areas rather than restoring the Golan itself.

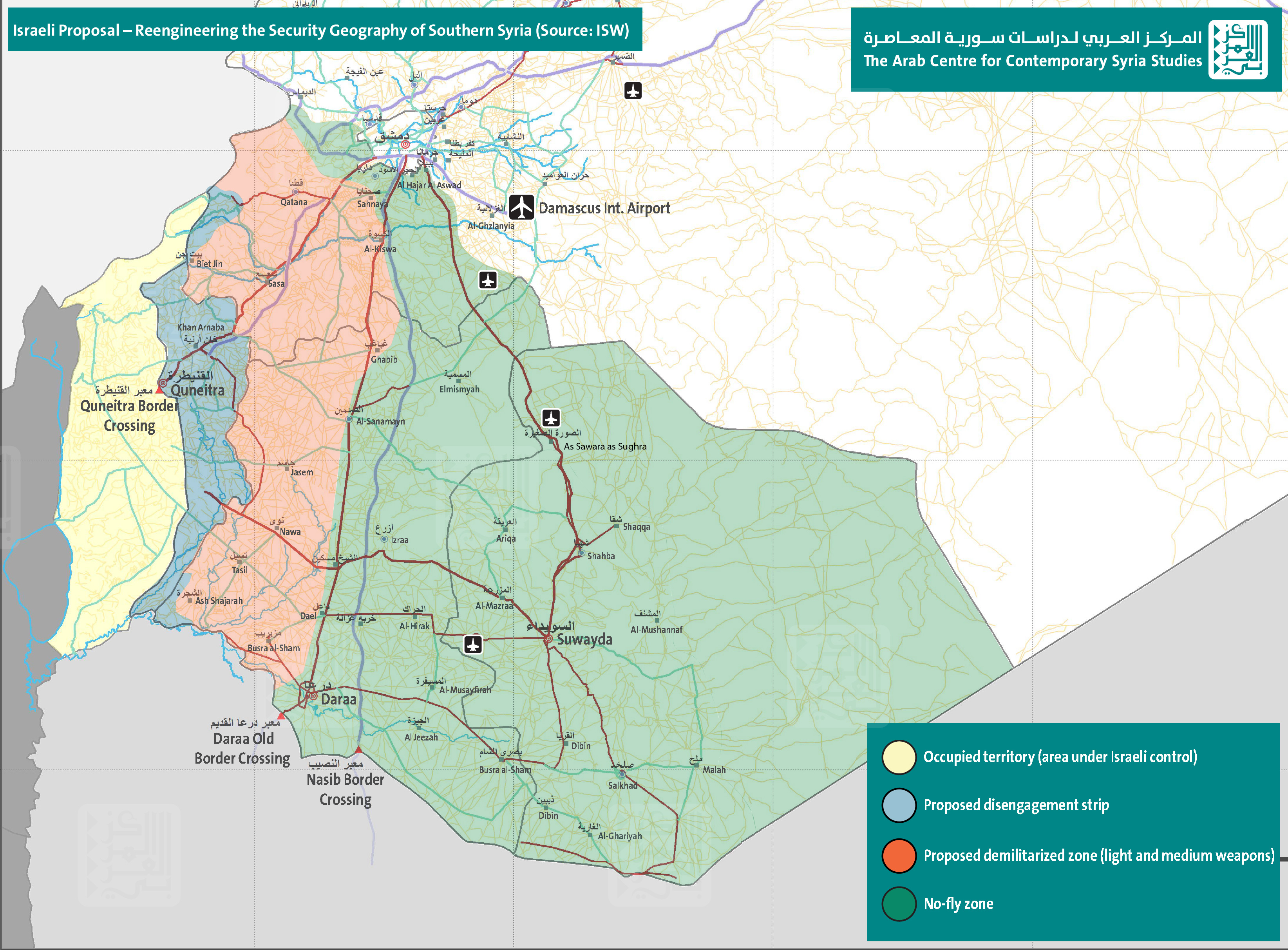

The proposal also envisages expanding the demilitarized zone by two kilometres on the Syrian side and designating the entire area from southern Damascus to the border as a no-fly zone for Syrian aircraft. As such, the Israeli plan discloses an attempt to re-engineer the security order of southern Syria by dividing it into distinct geographical zones, each with a specific status that constrains Syrian sovereignty. These include:

-

Yellow Zone (De-Facto Occupied): This strip would remain under Israeli security control and serve as a base for intelligence and strategic military operations.

-

Blue Zone (Disengagement Strip): The area directly adjacent to the border, historically known as the disengagement zone under the 1974 Agreement, to be managed under international supervision (e.g. by a monitoring force).

- Orange Zone (Demilitarised Zone): Extending deeper into Syrian territory, this zone would prohibit the presence of heavy weaponry and possibly restrict organised Syrian military deployment, without reciprocal arrangements on the Israeli side – thereby creating a de facto buffer between the border and the area of direct Syrian control.

-

Green Zone (No-Fly Zone): Covering large parts of the Daraa and al-Suwayda governorates and extending towards the environs of Damascus, this zone would impose restrictions on Syrian military aviation, thereby limiting Syria’s ability to project air power in the southern theatre.

The Israeli Proposal: Re-engineering the Security Geography of Southern Syria (Source: ISW)

Challenges of the Security Agreement

The Israeli proposal reflects an attempt to impose a new political and military reality, whereby vast areas of southern Syria would be rendered militarily detached from Syrian authority and placed under direct or indirect Israeli oversight. Moreover, if approved, the proposal would entrench Israeli influence across the southern governorates of Syria (Daraa, Quneitra, Suwayda, and parts of the south-western Damascus countryside). Under the pretext of ensuring stability, security, and the implementation of agreements, Israel would acquire the ability to carry out military incursions into these areas at will.

The agreement would also open the door to far-reaching Israeli interventions in Syria’s domestic affairs, particularly in areas with concentrations of the Druze community, under the pretext of protection. This would include Quneitra, Damascus countryside, and Suwayda. The Israeli proposal thus carries grave implications, as it undermines Syrian sovereignty over the south and threatens the territorial integrity of the country. It effectively treats these areas as outside the control of the Syrian state, reshaping their security status through arrangements with a foreign occupying power, rather than restoring the Golan and negotiating security provisions there.

The proposal also comes as both an embarrassment and a test for the interim Syrian government. Acceptance of such arrangements would entail making profound sovereign concessions from the very outset of its tenure, thereby jeopardizing its domestic legitimacy. The plan emerged shortly after Syria, Jordan, and the US had announced a preliminary roadmap to calm tensions in al-Suwayda and address the demands of its inhabitants. The Israeli intervention, framed as an alternative security order, undermines the possibility of building on that roadmap as a first step towards internal stability. It conveys the impression that security arrangements with foreign powers take precedence over domestic political solutions aimed at safeguarding Syrian unity. This weakens the credibility of the Syrian government and risks replicating the model of demilitarized or buffer zones elsewhere in the country, effectively dismantling national unity and fragmenting Syria into competing zones of regional and international influence. Both the hollow claim of central authority and the abandonment of the unity of the people and the land represent equally dangerous alternatives. Moreover, Israel’s success in carving out a buffer security zone in southern Syria would encourage other regional and international powers to demand similar arrangements and to impose sovereign restrictions on the Syrian state through military pressure were negotiations to fail.

Should Syria engage with this proposal, the interim government would face formidable political, legal, and security challenges, foremost among them the absence of constitutional legitimacy and popular mandate to conclude such an agreement. Any agreement with Israel – particularly one involving sovereignty and territory – requires legal and political authorization, including ratification by an elected parliament, which is not currently available. Given that the present government is, under the terms of the constitutional declaration, transitional, the signing of such an agreement would be subject to intense legal dispute, with some deeming it constitutionally void. It could also provoke rejection from large segments of the Syrian public, who continue to regard engagement with the Israeli occupation and agreements compromising Syrian sovereignty as crossing national red lines.

The Syrian public is widely opposed to any agreement with Israel. According to the findings of the Arab Opinion Index, 78% of Syrians view Israel as the greatest threat to the security and stability of the Middle East, 74% oppose recognizing Israel, and 70% oppose any agreement that does not secure the return of the Golan. Meanwhile, 88% believe Israel “is working to threaten security and stability in Syria,” and 74% contend that Israel is “working to support certain groups within Syrian society in order to fuel separatist conflicts and threaten Syria’s territorial integrity.”[10] Such indicators point to a risk of deepening internal divisions. Concluding security agreements with an occupying power historically hostile to the Syrian people, particularly while it wages a genocidal war against Palestine, without broad national consensus, could fracture Syrian society and political forces. Opposition may well emerge even within the ruling coalition, from factions unwilling to concede sovereignty.

In addition to popular opposition to any agreement that fails to secure Syrian sovereignty over its land, the acceptance of a demilitarized zone in the south would establish a dangerous precedent, infringing upon Syria’s legal right to full sovereignty over its territory and implicitly conceding to Israeli influence that requires special arrangements. Rather than affirming Syria’s right to restore the occupied Golan and enhance its defensive capacities, such an agreement would be read by Israel as Syrian acquiescence to a special security regime for the south –potentially paving the way for new de facto boundaries separating the region from the rest of the country. Added to this is Israel’s direct military presence on Mount Hermon.

The agreement also carries long-term security risks, as it would disarm a huge portion of Syrian territory, leaving it exposed to future Israeli incursions and assaults. Ultimately, acceptance of the buffer zone proposal would mortgage the south to an unequal equation for years to come, weakening Syria’s negotiating position vis-à-vis the occupation in any future talks over the restoration of the Golan Heights.

Conclusion

The Israeli proposal for the demilitarized zone in Syria represents a dangerous threat to Syrian territorial integrity, sovereignty, and long-term security. It exploits the country’s weak military and economic capabilities during the transitional process and its internal divisions, to impose a fait accompli serving only the interests of the Israeli occupation. Accepting this proposal, without popular consensus or constitutional legitimacy, would inflict historic damage on Syria’s position in the conflict with the Israeli occupation. Historical experience, from the Camp David Accords (1978), through Oslo (1993), and up to the Abraham Accords (2020), has proven that offering concessions or concluding separate peace agreements with Israel fails to reign in its expansionism. Rather, this has afforded Israel greater scope to entrench its occupation and impose new facts on the ground.

As such, any security arrangements concluded by Syria with Israel must remain within the framework of the 1974 Disengagement Agreement, without offering political recognition, implicit or explicit, of Israeli influence. Syria must maintain a principled position which does not allow it to relinquish its rights under pressure, refrain from signing any agreement that undermines Syria’s security, sovereignty, and territorial integrity, and affirm the necessity of returning to consult the Syrian people (through a referendum) or ratifying it through an elected parliament.

Existential questions that determine the fate of the nation are above the mandate of an exceptional interim government. Furthermore, the government must be transparent in addressing these issues, consult the people about the challenges and options at hand, and involve national elites in the discussions. It must also mobilize a popular, regional, and wider Arab stance rejecting any Israeli attempt to impose coercive arrangements in southern Syria. It must also refrain from revealing weakness in dealing with the challenges posed by Israel, which could be used against it. Instead, despite the difficult circumstances, Syria’s defence priorities should be restructured so that military capabilities are strengthened in the south, to send the message that any large-scale aggression or ground incursion will not be easy.

[1] “Al-Sharaa: We are very close to reaching an agreement with Israel through US mediation,”

Syria News, 20/9/2025, accessed on 21/9/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPvk

[2] “Syrian Foreign Ministry: Security agreements with Israel before the end of the year,”

Al Jazeera, 18/9/2025, accessed on 21/9/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPdS

[3] “UN Slams ‘Violation’ Of 1974 Syria Disengagement Deal as Israel Acts in Buffer Zone,” The Times of Israel, 10/12/2024, accessed on 21/9/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BP8j

[4] “Trump Meets Syrian President, Urges him to Establish Ties with Israel,”

Reuters, 14/5/2025, accessed on 21/9/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPj5

[5] “Syrian Foreign Minister Visits D.C. to Lobby for Lifting of Last Sanctions,”

Axios, 17/9/2025, accessed on 21/9/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPNd

[6] “Syrian Israeli Meeting in London Discusses De-Escalation within Framework of 1974 Agreement,”

The Jerusalem Post, 18/9/2025, accessed on 21/9/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPEA

[7] “Israel Presented Syria with Detailed Proposal for New Security Agreement – Report,”

The Times of Israel, 17/9/2025, accessed on 21/9/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPNr

[8] “Scoop: Israel Presented Syria with Proposal for New Security Agreement,”

Axios, 16/9/2025, accessed on 21/9/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPPS

[9] “Citing October 7, Katz says Israeli Troops Inside Syria Staying Put to Defend North,”

The Times of Israel, 26/8/2025, accessed on 21/9/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPE1

[10] “ACRPS Announces the Results of “Arab Opinion Index: Syria 2025”, Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, 31/8/2025, accessed on 21/9/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPrY