This article was translated by the ACRPS Translation and English Editing Department. The original Arabic version can be found here.

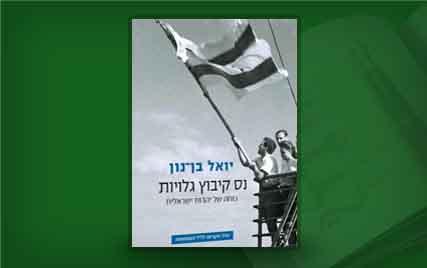

The Miracle of Gathering the Diaspora: The Strength of Israeli Judaism

Author: Rabbi Yoel Ben Nun

Published by Yediot Sefarim in 2011

The Israeli academic community and Israeli historiography consider the Zionist movement a secular movement led by secular Jews with the aim of resolving "the Jewish question" in Europe which appeared in the nineteenth century in response to ascendant anti-Semitism. According to this view, the movement aspired to end the state of "exodus" or "exile" and encourage migration to Palestine with the intention of establishing a Jewish homeland there. With the ascent of the religious current in Israel in recent years, its leaders and ideologues are attempting to rewrite the history of Zionism from a religious perspective, as is evident in the recent publication The Miracle of Gathering the Diaspora: The Strength of Israeli Judaism. The aforementioned book is not an academic book, but an ideological book which combines Jewish messianic-theological discourse with current political and historical realities. Moreover, the book is not written in contemporary twentieth-century vernacular Hebrew, but in historical biblical Hebrew rooted in nineteenth century Hebrew.

Unlike academic publications, reading The Miracle of Gathering the Diaspora requires knowledge of the author's background. This allows the reader to comprehend the book's main argument, which is premised on the understanding that the forced migration of the Jews from their native homelands and their settlement in Palestine - in other words, the "gathering" of the "Jewish Diaspora" - is not merely a human endeavor, but a godly act in line with the perceived history of Jewish exodus and reunion which dates back to the Jewish exodus from Egypt in ancient times according to the Torah. This book, therefore, can be considered a contribution to religious Zionist discourse in Israel. In this vein, the author attempts to rewrite the history of Zionism from the perspective of messianic Jewish thought, with the intention of serving and reinforcing the influence of religious Zionism. This is particularly important given that this historical moment in the evolution of the Zionist movement is witnessing the ascent of religious Zionism and its gradual success in presenting itself as the dominant intellectual and theoretical current seeking to shape and influence the movement and, thus, Israeli society. It must be noted that although this current does not enjoy the support of the voting majority, its followers are becoming increasingly influential in Israeli society and in the institutions of the state - especially in the army where more than half of the rank and file are visibly observing Jews. The traditional woven skullcap, or the kippah, is becoming a visible symbol amongst members of the army at different levels in the military hierarchy.

About the Author

The author of this book is Yoel Ben Nun, a prominent figure in the religious Zionist movement. Ben Noon was born in Haifa in 1946 and studied in the Mercaz HaRav religious institute in Jerusalem - a national-religious yeshiva (educational institution) which has been considered the stronghold of the religious Zionist movement since its founding at the hands of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, the father of national-religious Zionism. Ben Nun has been the chief rabbi and teacher at the religious school in Kfar Etzion in the occupied West Bank since 1967. Ben Nun is also a founding member of the Gosh Emunim movement, which is committed to building Jewish settlements in the occupied territories. He is known to have hosted the movement's foundational meeting in his house, giving birth to the first movement which combines messianic religious theology with expansive settlement building in Palestinian territories occupied in 1967.

I am a convinced Zionist and consider Zionism to be my driving ideology, whereas my Judaism and Israel constitute my identity. I believe that Zionism does not permit any separation between my being Jewish and my being Israeli. Moreover, Zionism is the complete and correct interpretation of the Torah of Moses, the thought of our elders, and the aspirations of our forefathers. (p. 11)

Rabbi Ben Nun starts his book, The Miracle of Gathering the Diaspora: The Strength of Israeli Judaism, with these words above. The book comprises of an introduction and five chapters. In the introduction, Ben Nun discusses the concept of salvation, which according to the book involves bringing an end to the state of "exodus" and bringing about a state of "return" to the historical "land of Israel". The first chapter historicizes the Jewish exodus from Egypt, whereas the second chapter examines the thoughts of Rabbi Yehuda Alkalai (Akalay) and Rabbi Kook. Chapter three discusses the "narratives of the Jewish tragedy", whereas chapter four examines the notion of Israel's "independence" and narrates the plight of its founding fathers and martyrs. The final chapter includes a set of prayers in celebration of Israel's "independence". Each chapter includes an examination of the concept of salvation from the perspective of Judeo-Zionist heritage. Moreover, the book invokes the works of a number of Jewish thinkers from various intellectual and ideological backgrounds, and their thoughts and opinions on the concept of salvation in its many forms. In doing so, The Miracle of Gathering the Diaspora examines and analyzes these thoughts and articulates the author's opinion and conceptualization of the notion of salvation.

This book can be considered an important contribution to Judeo-Zionist discourse and an attempt at shifting Jewish political thought towards Zionism by authenticating the Zionist theory and grounding it in Jewish history. It must be noted that this book is not an attempt at "zionizing" Judaism as much as it is an attempt at arguing that Zionism is an essential step towards Jewish salvation. In fact, the author argues that Zionism plays an important role in connecting Judaism with Israel, insisting that the arguments and theorizations of religious Zionism predate the political works of Theodor Herzl. The book, moreover, establishes Zionism within a historical, Jewish context as evidenced by the aforementioned quotation. In other words, The Miracle of Gathering the Diaspora does not only argue that Zionism is a historical project aspiring and contributing to salvation, but also a movement that has always been present in Jewish history.

In the first chapter, the author discusses the notion of salvation. In doing so, Rabbi Ben Nun questions whether salvation is a mere religious concept achievable only by God (Elohim), or if there is another form that is less transcendental. Ben Nun argues that salvation is neither momentary nor instantaneous, and that it cannot occur "from without history". According to Ben Nun, "It cannot be achieved within a single generation, nor can it be realized in a single historical transition." (pp. 32-34) In other words, salvation is a continuous process that characterizes Jewish history in its totality. This assertion is fundamental in Judeo-Zionist thought as it conceptualizes salvation not as a messianic, transcendental, and thus miraculous event, but rather as a political and historical process, although it is "godly" insofar as it is irreversible and mandated by divine will (p. 37).

The author then moves onto a study of the Jewish exodus from Egypt and raises the question of whether salvation is "natural" or "miraculous" (p. 74). This question, of course, is both a theological as well as philosophical question. In this respect, the author presents two narratives of the Jewish exodus from Egypt. According to the first narrative, championed by Rabbi Elazar Ben Azariah, the exodus from Egypt was a miracle. The second narrative, championed by Rabbi Akiva (Ben Joseph), argues that the exodus was "natural" - that is to say, in accordance with natural law. Rabbi Ben Nun insists that the Zionist project has depended more heavily on the conceptualizations of Akiva by understanding natural salvation as the intention and core of the message of the Torah. Even the miracle of Passover and the Jewish exodus from Egypt took place in accordance with natural laws (p. 76). This last statement further confirms the previous and reasserts that the Jewish exodus, and thus the "gathering of the Diaspora", does not occur through transcended and supernatural miracles. Instead, miracles occur within the bounds of social and natural laws. Miracles, according to this view, are part of history. More importantly, this viewpoint perceives the role of history in facilitating the circumstances for the occurrence of a miracle more significant and more miraculous in its own rite than a supernatural miracle as such.

Zionism and the Concept of Salvation

Following this theological and philosophical discussion of salvation, the author moves on to discussing the notion and applications of salvation in modern history (pp. 81-84). In doing so, the author combines the understanding that Judaism is a guarantor and a preserver of identity in the Diaspora and the understanding that the Zionist project is, in fact, a salvation project. Accordingly, Rabbi Ben Nun argues that the first phase of salvation occurred in 1840 when messianic fervor was high amongst Jewish communities in anticipation of the appearance of a messiah who would bring about the Jewish nation's salvation. Instead, the author contends, 1840 was not a year of salvation, but the year of a Jewish bloodbath in Damascus bringing about Ottoman rule in the historic land of Israel. As a result, Jews were struck with destitution and hopelessness, and thus resorted to Jewish identity (in its religious sense) as a bastion of their identity and unity. Others, however, abandoned Judaism altogether. Despite this blowing defeat, however, Rabbi Ben Nun argues that this particular year - 1840 - brought about the first phase of Zionist salvation, which was articulated at the hands of Rabbi Yehuda Alkalai (also known as Rabbi Akalay, b. 1798, d. 1878) long before Theodor Herzl. Akalay perceived the events of 1840 as the initial phase of salvation rather than a cause for destitution and hopelessness, in contradiction to mainstream Jewish thought at the time. Herzl, on the other hand, contributed to Jewish salvation at a much later phase, according to Ben Nun. This assertion, of course, is extremely significant insofar as it articulates the essential presuppositions of Judeo-Zionism, considering Herzl's secular form of Zionism a latter contribution to Jewish salvation rather than the core of contemporary Jewish history. According to this view, the Judeo-Zionist thought of such rabbis as Tzipi Hersh and Yehuda Akalay and their reinterpretation of history as told by the Torah represent the second phase of the salvation project. The third and fourth phases of Jewish salvation are constituted by such social movements as "Friends of Zion" and "The Zionist Movement". The Balfour Declaration of 1917, on the other hand, constitutes the fifth phase of this historical project, whereas the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 is the sixth.

In the next section of the book, Rabbi Ben Nun discusses the political thought of Rabbi Akalay and its relation to the work of Theodor Herzl as well as Rabbi Kook. As mentioned previously, Ben Nun considers Akalay a founding father of the Zionist project and a forerunner to Herzl, although Akalay may have been unaware of the repercussions of this to Jewish theology and political thought (p. 144). According to the author, Akalay established the notion of "ending the state of exodus" and, significantly, called for the establishment of a Jewish agency to represent the entire Jewish nation throughout the world. Through this agency, he aspired, "a unified leadership of the Jewish people would emerge." (p. 134) The notion of salvation and "undoing exodus" or "undoing exile", according to Rabbi Akalay, can be summarized in the following assertions: "exile" is not only a punishment for the Jewish people, but also a sin in itself. Accordingly, it must end by "returning" to the "land of Israel" en masse. Moreover, seeing as the "sin" of "exile" is comprehensive, the answer to it must be equally - if not more - comprehensive. "Returning" to the land of Israel must be comprehensive, irreversible, and well organized so as to succeed. This is yet another indication of Akalay's contribution to organized Zionism prior to Theodor Herzl's contribution to contemporary Zionism. According to Akalay, the notion of atonement and repentance at the end of history as discussed in the Torah is understood as an indication of the importance of returning to the land of Israel and, thus, achieving salvation (pp. 137-138). Akalay, therefore, establishes and connects the notions of "return" and salvation - in their comprehensive and collective sense - and refutes the notion of individual migration to Palestine in anticipation of a supernatural messianic salvation as advocated by the more mainstream Jewish thinkers of the time. Instead, the Messiah, according to Akalay, must work within the bounds of natural law and political realities to achieve the messianic salvation of the Jewish nation (p. 161).

In the following sections of the book, Ben Nun discusses "narratives of the Jewish tragedy", asserting that the waves of "hope" and "belief" which followed each Jewish tragedy were essential in the production of salvation (p. 193). Ben Nun discusses the tragedies of Israel's "independence war" in 1948, and its human and material losses in a similar vein. The final section of the book includes selected prayers in commemoration and celebration of the independence of the Jewish nation and the creation of the state of Israel. The author, therefore, draws upon and contributes to the Judeo-Zionist conceptual notions of salvation. In this respect, the latter sections of the book appear less significant and more narrative than the first sections of the book, which engage in a theological and philosophical debate over the nature and dynamics of salvation through the notion of "gathering the Diaspora" and "undoing exile".

In this vein, the author sees enough strength in the Zionist project to prevent such a schism as that which existed between the ancient Jewish kingdoms of Judea and Samaria at the time of the Second Temple (Beth Hamikdosh). The Zionist project, he contends, is capable of uniting those who believe in and stress on their Jewish identity as superior to their Israeli identity (such as Israeli settlers in Palestinian territories occupied after 1967) and those who prioritize their Israeli identity over their Jewish belongingness (such as the more secular inhabitants of Israel). This, Ben Nun argues, is because Zionism connects the two identities and the two concepts - the Jewish nation and the State of Israel - as the Israeli Declaration of Independence stipulates (p. 290). According to Ben Nun's The Miracle of Gathering the Diaspora, the state of Israel was born to achieve a single fundamental goal: undoing exile and gathering the Diaspora. This objective must continue to enjoy consensus from the various political and social factions of Israeli society and the Jewish nation at large. As a result, the notion of "post-Zionism" poses a threat not only to Zionism itself, but to the very coherence of the state of Israel and the Judeo-Zionist movement.

It is in this very assertion that the significance of Ben Nun's The Miracle of Gathering the Diaspora lies, especially with regard to the notions of "Jewish exile" and "exodus". In other words, to be a Zionist, one must "return" to the land of Israel. This "return", the book contends, is a historic mission rooted in Jews' exodus from Egypt, and continues to define Jewish history and heritage. These assertions are in line with much of the Judeo-Zionist discourse, which gives the Zionist mission and project a historical, messianic, and thus salvationist dimension. In doing so, the book argues that Zionism is not merely a secular political mission, nor is "exile" a religious sin per se. Instead, Zionism embodies the continuous and perpetual historical attempt to achieve salvation, which has a temporal and momentary dimension. Moreover, Zionism connects and combines Jewish identity and Israeli identity. Of course, Ben Nun does not differentiate between "Jewish identity" in its communal and cultural sense and "Jewish identity" in its theological sense as the secular movement often contends (with little success in achieving and internalizing this distinction). Instead, Ben Nun refers to a religious Jewish identity inseparable from the cultural Jewish identity. It can therefore be argued that this assertion is the starting point in an ascendant move towards dominating Zionist discourse and the definition of the Zionist mission by stressing on the religious Judeo-Zionist conceptualization of the concept and mission of Zionism - a movement that predates Theodor Herzl himself. In this respect, Zionist identity becomes more attainable by adherence to this worldview, whereas it becomes less attainable by those who cannot reconcile the two identities within this worldview. Moreover, since Zionism has been an omnipresent influence and a defining factor in Jewish history and heritage, adhering to "true Zionism" becomes contingent on one's ability to connect it with the salvationist message of Zionism and Judaism itself. As a result, Ben Nun invokes and stresses on the classical Zionist assertion that the Zionist project is a divine mission par excellence, insofar as it aspires to achieve salvation. In light of this, the forces carrying this historic mission become instruments of a divine mission, and servants of God. Accordingly, "gathering the Diaspora" and "undoing exile" becomes a miracle in the religious sense - although it can only be attained through the laws of nature and society.

The Miracle

The book attempts to theorize and explain these concepts and assertions through the epistemological methods of the Torah and its salvationist message, arguing that the "gathering of the Diaspora" prior to the creation of the state of Israel, the "reunion" of some 600,000 Jews in the historical land of Israel, and the migration of some three million Jews to Israel following the establishment of the state, is "the greatest miracle, unprecedented in the history of the Jewish people or in the history of any other nation, and will never be repeated in the future." (p. 83) This claim reiterates and reinforces the salvationist dimension of the Zionist project. In light of this, Rabbi Ben Nun argues that the "gathering of the Diaspora" has been the focal point of the Torah, the works of Jewish elders, and the intellectual heritage of Jewish peers and forefathers between the destruction of the Second Temple and the sixth century AD. In essence, connecting the Jewish exodus from Egypt with the "return" of the Jewish people to the historic land of Israel contributes to this salvationist discourse. In the former, the "miracle" of Passover involved the escape of the Jewish people from a particular location (Egypt) under the leadership of a particular person (Moses), whereas their "return" to the land of Israel is an unprecedented miracle insofar as it brought together the Jewish people from all over the globe.

The assertions of the Judeo-Zionist discourse can be traced back to the works of Rabbi Kook and his son, Rabbi Koon Jr., which emphasize the salvationist nature of the Zionist project, placing the Zionist movement within the context of religious salvation as conceptualized by Jewish theologians. What concerns us here, however, is that the Jewish salvation project is perceived as a continuous and perpetual project: as long as there remain Jews "around the world" or "in exile" - according to the theological characterization - the mission of "undoing their exile" and "gathering" them in the historical land of Israel is in effect. "Gathering the Diaspora", therefore, becomes a continuous human process that has not and will not end. It is in this respect that Zionism is perceived as a significant ideology, insofar as it merges Jewish and Israeli identity into the single, unifying process of the Jewish "return" to Israel. The book, therefore, refutes all notions of a "Jewish exile" and argues against the opinion that Jews are capable of combining their "exile" with their preservation of their Jewishness. In other words, Rabbi Ben Nun refutes the opinion that the transition towards divine salvation and "reunion" has not begun and, by extension, that "Israel" is in fact a Jewish state of "exile". In other words, the book opposes the view that Judaism can retain its spiritual purity and uncorrupt nature while Jews are in "exile" away from the land of Israel.

Significantly, the author considers that there may be non-Jewish contributors to the salvationist mission of the Zionist movement as evidenced by Jewish history, from Jews' exodus from Egypt up to their "reunion" and "return" to Israel. During the Jewish exodus from Egypt, for instance, Moses identified non-Jewish escapees amongst his flock. This, Ben Nun notes, may cause several problems for the Jewish salvationist aspiration, although Jewish elders and prophets have indicated that the salvationist project will be capable of coping with these impurities and problems. The author, therefore, confines his analysis to messianic and predictive works of Jewish elders to foresee potential problems and predict their solution. Essentially, Ben Nun perceives the "gathering of the Diaspora" as a divine miracle that God alone has mandated and will ensure, although man and natural laws are the defining factors in the achievement of this missionary miracle. The book, therefore, refutes transcendental and essentialist conceptualizations of the miracle which stress on the supernatural dimension. Instead, the miracle entails historical and "natural" progressions that lead to the achievement of the divine promise.

The book entails another significant assertion which may not be new or unprecedented, but is important insofar as it is articulated by a Jewish Rabbi. According to the author, Judaism alone could not have brought about the birth of the state of Israel because Judaism, in its pre-Zionist sense, consumed itself with preserving Jewish identity in spite of "exile" and maintaining the Jewish faith amongst Jews "in the Diaspora". In fact, Judaism - Ben Nun argues - contributed to the prolonging of the state of exodus amongst the Jewish people and delayed the "renaissance" of the Jewish nation. On the other hand, Israeli identity in its secular sense cannot explain the establishment of the Jewish state on the historic land of Israel. The connection between the two questions, the author argues, is the key to understanding and, hence, preserving the state of Israel and the "gathering of the Diaspora" as the Declaration of Independence articulates. This is evidenced by the declaration's assertion that "The land of Israel was the birthplace of the Jewish people." In other words, Jewish identity - as a project - contributed to the survival and sustainability of the salvationist mission, whereas Israeli identity provided the infrastructural and institutional framework. The result, therefore, is the Zionist movement, which merges both identities in an attempt to realize salvation in its religious as well as social and political sense.

Conclusion

This book can be considered a defining contribution and an essential reading for scholars with an interest in the Zionist movement, Israel, and Jewish identity construction. The Miracle of Gathering the Diaspora provides some essential insights into Israeli and Jewish society, and makes some important contributions and remarks on religious Zionism and Judeo-Zionist discourse, which are becoming increasingly omnipresent in contemporary Israeli society even if they have not resulted in the crystallization of a significant electoral bloc. Moreover, the book reiterates the fundamental and controversial salvationist message of the Zionist movement, which combines Jewish and Israeli identities by invoking classical theological notions of salvation, in combination with a thorough understanding of history and contemporary politics and society.

Rabbi Ben Nun is seen as an icon of the more moderate faction of the Judeo-Zionist movement. This, however, is not entirely true as he reiterates the same messianic ideals and salvationist concepts that he shares with other factions of Judeo-Zionism. Ben Nun, it must be noted, contextualizes these notions within more contemporary discussions. Interestingly, Ben Nun does not see the Jewish "return" to the land of Israel as the sole purpose or manifestation of Jewish salvation, nor does he see Arab and Palestinian citizens of Israel as equal citizens or integral components of the exclusively Jewish state, seeing as "Israeliness cannot be attained without Jewishness" and "both cannot be attained without Zionism."