Introduction

Groups of armed Tunisians loyal to the Islamic State (ISIL) organization carried out a series of coordinated attacks in the early hours of Monday, March 7, targeting the Tunisian National Guard, the security services and army posts located in the city of Ben Gardane along the border with Libya. Following a rapid and effective response from the Tunisian security forces, calm and order were restored. Claiming responsibility for the terrorist attack, ISIL vowed to avenge the deaths of the assailants killed by the Tunisian authorities. The recent events bring a number of questions to the forefront: why did the attackers choose Ben Gardane specifically? What objectives did ISIL hope to achieve by carrying out the attack? What strategies does the international terrorist network rely on when trying to infiltrate Tunisian society? And what do the answers to these questions tell us about the methods needed to confront the challenges facing Tunisia today?

Why Ben Gardane?

Ben Gardane lies in the Medenine Governorate, at the southeastern edge of Tunisia, adjacent to the Ras-Jadeer border crossing with Libya. Lying at a crossroads, the city of Ben Gardane has long been an important economic artery for the entire south of the Tunisian Republic. A hot and dry city, Ben Gardane has 80,000 residents. Despite the city’s cultural and natural wealth, Ben Gardane has been marginalized throughout Tunisia’s modern history, with no agricultural or industrial investment poured into it. As a result, its citizens have been driven into the shadow economy and many have become smugglers. With the collapse of the Gaddafi regime next door, the smuggling routes which tie the Tunisian city to North Africa have expanded beyond the normal remit of petrol and consumer goods, to human trafficking and weapons smuggling. Current clashes in Libya between the various factions has resulted in the breakdown of these traditional smuggling routes, plunging the city of Ben Gardane further into desolation, and threatening to exacerbate youth unemployment in the city.

|

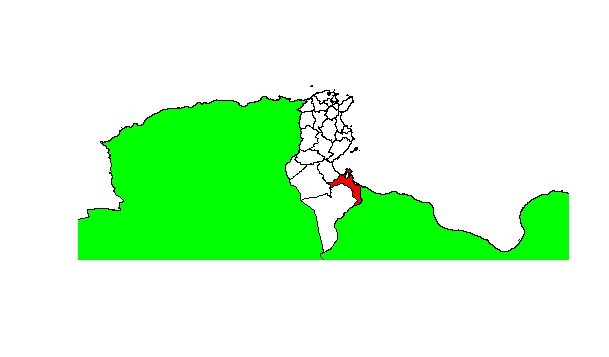

| Map of Tunisian Governorates, with Medenine Shown in Red; Algeria (to the West) and Libya (to the East), both shown in green. |

Ben Gardane’s legacy as a city of virtuous struggle stretches back to Tunisia’s pre-independence period. In the waning days of the Ben Ali regime, the city was also the site of massive public protests in 2010, resulting from a series of economic decisions made during a spat between Libyan and Tunisian authorities. These included the decision to rely on a maritime shipping route between the ports of Sfax and Tripoli, serving to reduce demand for land freight between the two countries; a subsequent decision by the Libyan authorities to impose a 150 Libyan Dinar levy (€80 in 2010 currency); and finally, as retaliation, a crackdown by Tunisian authorities on the sale of Libyan goods within Tunisia, except by holders of import and export licenses. The last measure was particularly harsh on the citizens of Ben Gardane, who had long been denied access to formal licenses by the authorities in the capital, and whose livelihoods were badly affected. Protests focusing on employment rights rapidly erupted in Ben Gardane. These, alongside the 2008 protests in Gafsa sparked what would become the much broader country-wide revolution that toppled Ben Ali. This tradition of rebelliousness lived on after the dictator’s fall, as the people of Ben Gardane continued to protest their neglect by the central authorities.

ISIL Objectives in the Ben Gardane Attack

A number of factors indicate that the attack on the bases in Ben Gardane was carefully planned. These include:

- The presence of a number of weapons caches in the area, alongside the activation of a number of sleeper cells which scurried to join the original attackers

- Orchestrated tactics by the attackers to terrorize the people of Ben Gardane, by running through the streets and summarily executing citizens and security officials at random.

- Attempts to win over the sympathies of the people of Ben Gardane by highlighting their long-term neglect by the central authorities.

There are two approaches to the interpretation of the tactics used by the attackers. One school of thought holds that the ISIL- affiliated militants sought to test the responsiveness of Tunisia’s security forces and military, and to measure the extent of their preparedness. In this reading, the March 7 assault was merely a dry run for what will be longer lasting attacks in the future, and which will ultimately aim to implant ISIL rule in some regions of the country. A second interpretation views the March 7 attack as an attempt to gain control of Ben Gardane, which could eventually become an operating base for ISIL, to be utilized if the group is pushed out of Libya or if its bases there come under attack.

In the event that ISIL could gain control of Ben Gardane, the group would be able to infiltrate its fighters across southern Tunisia. Notably, Islamic State fighters are presently spread across the Western frontier of Libya. One of the details which corroborates such a maximalist reading is the simultaneity of the attacks on the military bases and police and security headquarters, clearly indicating the assailants’ wish to incapacitate all state organs at once and pave the way for their dominance of the region around Ben Gardane. With the capture of the provincial governor’s office, and its symbolic conversion to an ISIL base, and the capture of the courthouse and its transformation into a courthouse administering Islamic law, this transition could be complete. Testimony from several captured attackers seems to support this latter, more expansive interpretation of the aims and ambitions of the attackers.

ISIL Infiltrates Tunisia

A total of 49 attackers were killed, with identities confirmed for 23 of them in total, of whom one was an Algerian (the others being Tunisian nationals). A further 30 members of the group, again all Tunisians, were also captured by the Tunisian security forces during the course of the attack. Almost all of the attackers were under 35 years of age, with a few older members coordinating the attacks behind the scenes. The terrorists’ familiarity with the streets and locations within Ben Gardane, suggests that the group carrying out the attack was made up of natives of the city or, at the very least, people who had lived there long enough to become fully integrated with its rhythms: the attackers seemed to know the identities of their targets, in one case assassinating the regional police director of anti-terrorism in front of his home. Another possibility is that they were able to make use of sleeper cells, of which scores are strewn across southern Tunisia.

The fact that the Islamic State group can rely on large numbers of supporters in Tunisia did not come as a surprise; multiple sources have long confirmed that Tunisian volunteers comprise the second largest national group in ISIL ranks in Iraq and Syria. By December, 2014, ISIL had taken responsibility for a number of terrorist attacks inside Tunisian territory: in a video recording, the group had claimed to have been responsible for the assassination of two Tunisian labor leaders, and demanded that Tunisians make fealty to Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi, the ISIL chief stationed in Iraq. Only a few months later, ISIL had claimed that attackers affiliated with it had carried out the now-infamous twin massacres on March 18, 2015, where 22 people (of whom 21 were foreign tourists) were killed outside the Bardo Museum and a further 38 victims (mostly British tourists) were killed outside their hotel in the city of Sousse. In April, 2015, Abu Yahya El Tunisi had issued an invitation to Tunisian jihadists to join him in the self-proclaimed “Vilayet of Tripoli”, from where they could train and prepare for the capture of their own home country and establish an Islamic caliphate there. The ranks of these fighters swelled as Russian attacks on Syria drove many Tunisian supporters of ISIL back into North Africa. By November, ISIL affiliated groups were claiming responsibility for blowing up a presidential guard bus, killing 12 members of that elite group.

The latest attack on Ben Gardane, however, represents a turning point. Previous ISIL attacks within Tunisian territory, horrific as they were, were limited to single acts of violence, such as assassinations or attacks on tourists. This latest attack is fundamentally different in its attempt to gain control over a number of crucial institutions along the country’s border with Libya. Yet the Ben Gardane attack is also the latest in a string of planned ISIL attacks in Tunisia, the rest of which had been consigned to failure. Indeed, when a US airstrike had taken out an ISIL-affiliated base in the Libyan city of Sabratha, a mere 70 km from the border with Tunisia, more than 50 Tunisian militants were reported killed. At the time, the United States claimed that the airstrike had prevented another terrorist disaster from unfurling in Tunisia. The March, 2016 attack in Ben Gardane, seems intended, among other things, to undermine those efforts by the US.

Potential Fall Out?

The attacks in Ben Gardane clearly pose a real threat to Tunisia’s fledgling democracy. By intensifying public desire for stability and law and order, they could ultimately serve to bolster Tunisia’s security services. This could serve to restore the Tunisian police to its pre-revolutionary immunity from all political restraint. Seeking to find a silver lining in the cloud of these attacks, Tunisia’s security forces would welcome the opportunity to turn back the clock on the country’s progress. Emerging recently from a clash with the central authorities over members’ pay, where many members of the security services took to the streets of the capital Tunis on February 25, and openly denounced the prime minister, Tunisia’s police and the deep state are waiting in the sidelines for the opportunity to strike back. These terrorist attacks provide a golden opportunity for Tunisia’s police to present themselves as the country’s saviors, and the institution most capable of safeguarding the country from the threat of terrorism. On a regional level, too, the impact of these attacks is likely to be felt, with Tunisia now less likely to oppose international intervention in the affairs of its next door neighbor, Libya. With the stakes so high, and the possibility of ISIL’s affiliates in North Africa being allowed to roam free, it’s no wonder that many Tunisians are prepared to countenance these actions. No such actions, however, will relieve the Tunisian government of its responsibilities to put in place a strategy that prevents ISIL from being able to recruit so easily among Tunisia’s disaffected youth. For it to be successful, such a strategy must go beyond vigilance in the security sphere to also include greater development, expanded freedoms as well as the expansion of democratic praxis.

To read this Assessment Report as a PDF, please click here or on the icon above. This Report is an edited translation by the ACRPS Translation and English editing team. The original Arabic version appeared online on March 17, 2016 and can be found here.