Introduction

Forces loyal to former Libyan Colonel—and erstwhile CIA asset—Khalifa Haftar were able to capture the cities of Waddan and Sokna as well as the nearby airbase at Jafra on June 3. The group, which calls itself the “Karama Forces” were able to make their advance on the two cities after days of sustained aerial bombardment. Continuous airstrikes were conducted by fighter pilots loyal to Khalifa Haftar with support from the Egyptian Air Force. The capture of the Jafra Airbase, meanwhile, was undertaken in the same way as the conquest of the Oil Crescent last September: by trades and building tribal alliances[1].

Control of the Jafra Airbase offers the Haftar forces a significant battlefield advantage. It comes only a few short days after they took another air base at Tamanhent, on the outskirts of the southern city of Sabha (also known as the Sabha Airbase). The Jafra Airbase adds a distinct geographical advantage, allowing the Karama Forces to control movement from eastern Libya and the Oil Crescent towards the south. It also denies the Benghazi Defense Brigades a rear operating base from which to launch strikes against Haftar Loyalists in the Oil Crescent. The Jafra Airbase also provides a commanding position over the desert landscapes and valleys to the south of Sirte. Added to the Haftar loyalists based to the east of Sirte, this allows the Karama Forces to encircle the city entirely. The first attack on one of the main highways into Sirte began on June 2. This sent a clear message to the revolutionary forces in Misrata, who are already depleted by an earlier drive to push the Islamic State out of their city which left 800 dead and 3,000 wounded in their own ranks.

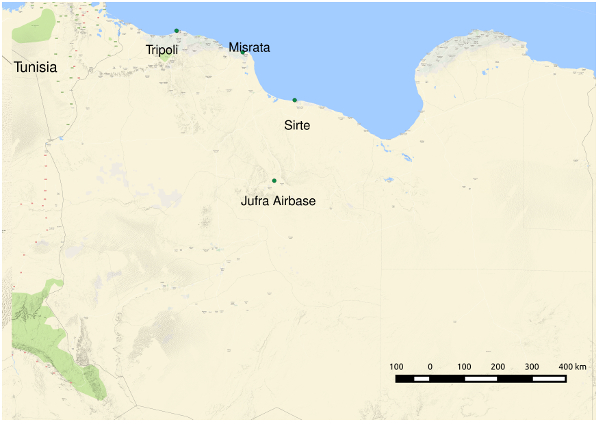

|

| Various sites and towns in Libya, June 2017. |

The strategic significance of controlling Jafra goes beyond this however. Given the geographic and social factors, it is likely that the Karama Forces will launch a campaign to seize the Bani Walid area, which is joined to Jafra by a highway. The only inhabited areas along the road are populated by the Ourfala tribe, which has no history of conflict with the Karama Forces since the latter were first formed in early 2014. If such a situation comes about, it would mark the beginning of an effective siege of Misrata, surrounding the city on both the eastern and southern flanks. It could also force the revolutionary forces presently tied up in Sirte to move to defend Misrata.

The March to Tripoli

Khalifa Haftar makes no secret of the fact that his ultimate ambition lies in the capture of the Libyan capital, which would give his forces control of the western region of Libya after cementing their control over the east. Col. Ahmad Al Mismari, Spokesman of the Karama Forces, affirmed in statements to the press that the troops under Haftar’s command would find it easier to move in on Tripoli now. Setting Haftar’s wishful thinking aside however, capturing Tripoli would be significantly more complicated than either Taminhint or Jafra.

The Karama Forces had geography on their side when trying to take those earlier cities. It was relatively easy for the fighter jets under Haftar’s command to attack isolated military outposts and for his ground troops to take towns scattered across the desert. With the support of the Egyptian Air Force as well as the planes under its control, Haftar’s forces faced minimal difficulty in draining the energy of the rebels holed up in the small, desolate towns outside of the Jafra Airbase. Together, these forces were able to launch precision airstrikes against the rebels in Jafra as well as the infrastructure in the surrounding areas and farms.

Tripoli will be a different story. The large, sprawling capital of Libya is surrounded on all sides by a set of suburbs which would pose obstacles for an advancing army. Even the aerial forces at Haftar’s disposal will likely be impaired when attempting to strike at targets in Tripoli and its environs. To begin with, the effectiveness of precision strikes will be reduced when facing agile, lightly armored rebels. On the other hand, unleashing massive firepower from the air in a densely populated area would lead to massive civilian casualties. This, in turn, would destroy Haftar’s credibility among a wide swathe of the public who might otherwise be persuaded to support him as a savior following the breakdown of security in a post-Gaddafi Libya.

Political and social factors also complicate any advance by Haftar onto Tripoli. Unlike the Libyan hinterland, the capital city cannot be taken by a series of negotiations and back-channel trades with tribal groups. This is clear from recent clashes between forces loyal to the National Salvation Government (headed by Khalifa Ghwali) and the Government of National Accord in Tripoli. These groups and similar armed formations in the Libyan capital are brought together by ideological affiliation and personal loyalties, not bound by tribal or other parochial codes. What all of the major armed factions in Tripoli have in common is their distaste for the Karama Forces. Although they have yet to overcome their own internal divisions and create the environment needed for the reconstruction of state institutions, they are also adamantly opposed to Haftar’s plans to bring in a military government.

Faced with this situation, Haftar will likely be unable to fully take Tripoli the way he wants. Instead, he will have to make do with possible inroads into the capital that could help him cause havoc there. This includes the diversity of citizens who expectedly live in the capital city. This necessarily includes some people who support Haftar for their own family connections to regions which are in favor of the Karama Forces leader, and other groups who are frustrated at the inability of either the GNA or the Salvation Government to bring about peace and prosperity or even to disband the militia and create a police service. The disputes between various competing factions in Tripoli have demonstrated that the real enemy of the February 14 Revolution and democratization of the country is the warlords’ petty bickering, their narcissisms and their failure to abide by any kind of institutional heirarchies within the state.

In the environment of these machinations, the leader of the Karama Forces will be faced with the powers that be around Tripoli. This includes armed groups in and around Warshefana to the southwest of Tripoli that are likely to be favorable to Haftar, but also the Zintan Brigades to the southeast, whose relationship with the Karama Forces has been openly tense for months.

Regional Factors Cast a Shadow

No matter how powerful domestic factors might be, any decision by Haftar to go after the capital could never be an entirely Libyan affair. Earlier examples of how regional actors made themselves felt on the Libyan scene could be found in Haftar’s taking of Dirna. This was only possible with Egyptian aerial support, and the landing of Egyptian Special Forces in and around the city as well as logistical backing from the United Arab Emirates which shipped weapons and ammunition to the Karama Forces via the Port of Tobruk. Today, the UAE’s infractions of an international weapons embargo on Libya is no longer a secret, with numerous UN reports condemning the violation of the arms blockade. Beyond material support, the UAE has also placed an air force unit at the Bneina airbase near Benghazi, which even the leadership of the Karama Forces no longer denies.

Haftar’s capture of the Jafra Airbase, and his threat to go after Misrata and Tripoli is coupled with the recent release of Saif-al-Islam Gaddafi (another ally of Abu Dhabi). The latter may end up with a political future in Libya, signalling the determination by some to simply send Libya back to its pre-revolutionary status. Having succeeded to return Egypt to its pre-Arab Spring state of military rule, governments across the region believe that they can repeat the same trick today in Libya. If successful, the regional anti-democratic, counterrevolutionary coalition could in turn find a way to an onslaught against Tunisia’s emerging fragile democracy, or even to use this power against Algeria, which has thus far attempted to play a mediating role in Libya and avoid being dragged into Egypt’s war.

Conclusion

Haftar’s capture of the Jafra Airbase has been a success, politically and militarily, which will likely change the balance of powers on the ground in Libya. While the factors which enabled Haftar’s capture of Jafra and other locations are not replicated across other regions in the center or west of Libya, these events will likely also embolden a growing regional alliance committed to turning back the clock on the Arab Spring in every country to witness change since 2011. In this, they seemingly have the tacit support of a sympathetic White House.

To read this Report as a PDF, please click here, or on the icon above. This Report was translated by the ACRPS Translation and English editing team. To read the original Arabic version, which appeared online on Monday, 12 June, please click here.

[1] See “Al-Massari: Seven killed in battles of Jafra”: http://www.eanlibya.com/archives/122387