Introduction

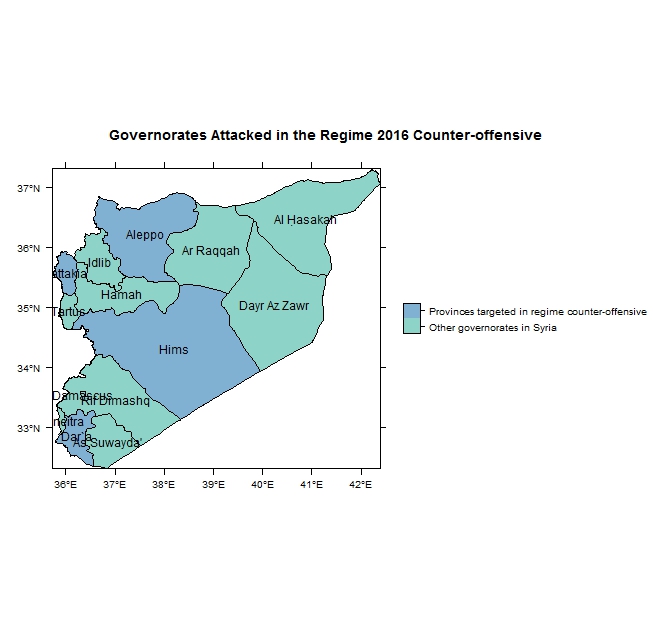

Even as preparations were underway to reinvigorate the Geneva-based peace process – moribund since 2014 – the Syrian regime and its military allies carried out a massive military offensive across four key governorates of Syria: Homs, Aleppo, Lattakia, and Deraa. Despite heavy casualties, Assad’s regime forces were also able to make considerable military gains thanks to a constellation of factors, the most vital of which was cover provided by Russian aerial bombardment. With this support, the Syrian regime was able to completely redraw an on-the-ground tactical map across large parts of Syrian territory. Although observers are now accustomed to Syrian regime forces scurrying to capture territory in the run-up to new negotiations, this latest episode goes beyond what is usually a tactical ploy by Damascus to gain the upper hand at the negotiating table. Instead, this most recent development shows a wish on the part of the Assad government to draw the broad outlines of a political settlement The timing here is deliberate: with American acquiescence, Moscow is using its full military might to break the back of opposition forces, and thereby secure a settlement that is favorable to its allies in the Assad regime.

|

| Governorates of Syria: those governorates involved in the regime's February, 2016 counter-offensive are in light blue. Clue to enlarge. |

Taking Territory, Re-Drawing Political Maps

The Azaz Corridor

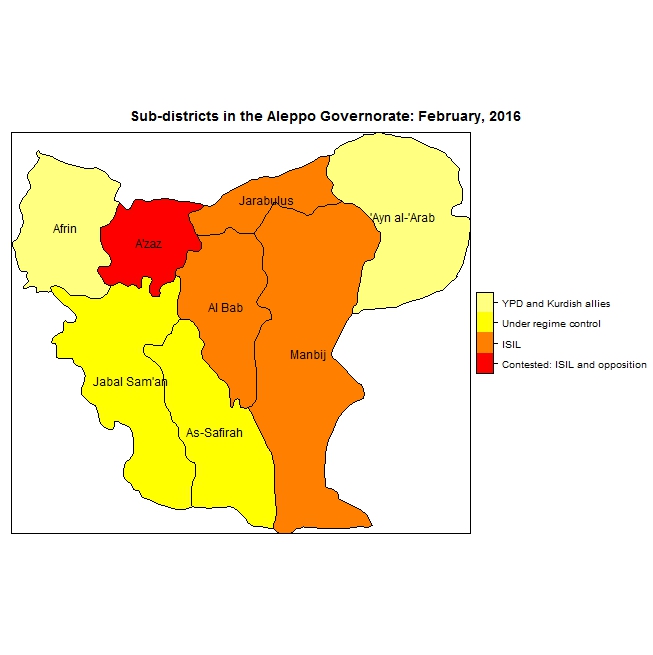

Today, most of the 910 km Syrian-Turkish border that lies to the East of the Euphrates is controlled by fighters of the PYD, drawn mainly from the military wing of the Kurdistan Democratic Union Party,[1] which is backed by both Moscow and Washington. Only a short 160 km strip on the West Bank of the Euphrates remains outside of the control of this Kurdish group. This is a remarkable feat since three groups are currently vying for control of the borderland; the opposition, Assad forces, and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), the latter of which controls a 98-km road between Jarabulus and Azaz as well as a 13-km stretch between Azaz and Afrin. The rest of the Syrian-Turkish frontier, stretching out to the Mediterranean and the province of Iskenderun (within the Republic of Turkey) remains under the command of the Syrian-Kurdish YPG.

By attacking the Syrian opposition forces at this critical juncture in the conflict, Russia aims to cut off the supply routes which link the opposition-held regions described above, in the north of the Aleppo Governorate, with the outside world. In this regard, a high priority target is the Azaz Corridor, which provides a lifeline to the opposition in the Aleppo Governorate. This strategic aim is in fact shared by Washington, which is using the Kurdish forces that it supports in a proxy war to contain ISIL within the boundaries of Syria before its final push to completely destroy the group.

Russian intervention has already provided the air cover needed to lift the opposition’s siege on two majority-Shia towns aligned with the regime, Nubl and Zahraa. By putting the towns back in the control of the regime, the supply route that tied the opposition-held town of Azaz to the parts of Aleppo held by the opposition was cut off. This leaves the opposition held portion of Aleppo under a three-sided siege: by the regime forces to the south and the north; ISIL forces to the north and the east; and PYD forces to the west.

|

| Districts within the Aleppo Governorate and their respective controlling parties. Click to enlarge. |

At the same time, Russian aerial support aided the advance of the PYD, and allowed them to further entrench their choke-hold on the road that links the city of Aleppo to the town of Azaz. By February 4, the Kurdish fighters were able to capture a further two towns to the north of Nubul and Zahraa: Al Khirbeh and al-Ziara. By February 10, a group calling itself the “Revolutionary Army” alongside the overall command of the YPG had secured the strategically important military airfield at Minaq, less than 7 km from Azaz. This advance, however, came at the expense of the anti-ISIL groups within the Syrian opposition. These forces will likely continue to march northward toward the border with Turkey, thereby freeing the regime’s regular forces to consolidate their positions in and around the city of Aleppo. In other words: the division of labor between the regime and a number of militia and irregular forces – including the YPG – is clearly underway in the Aleppo Governorate.

By dividing the north of the Aleppo Governorate into two separate regions and cutting each off from supply lines into Turkey, the regime is effectively creating a buffer between itself and any prospective ground offensive against ISIL forces based in the Aleppo Governorate. Any military leading such a campaign against ISIL, be it Turkish or Saudi Arabian, would face the prospect of a direct confrontation with the regime and its allies, which is a distinct disincentive. Indeed, Washington’s reluctance to be embroiled in a direct military conflict with the Syrian regime could explain the lukewarm American reception of the Saudi offer to lend ground forces to take part in a US-led force to tackle ISIL in Syria. Today, focus has shifted to a Russian overseen military strategy, which will see a military offensive launched from the city of Khan Toman (southwest of Aleppo) aimed towards the Idlib Governorate. If successful, this offensive would allow the regime and its supporters the chance to completely encircle opposition forces in Aleppo, and to free up its supporters in the towns of Kafraya and Faoua in the Idlib Governorate.

The Battle in the South

The military front to the south of Damascus is no less vital strategically than the fighting underway in the Aleppo Governorate. In Deraa, the scramble to secure the governorate’s Nusaib border crossing with Jordan is the regime’s primary aim. The symbolic significance of the regime regaining control of its borders with neighboring countries would be important since it would show the international community that the regime is no longer in a position of isolation.

A shift in Russian policy ultimately helped the regime forces regain the border town of Sheikh Maskin. While Russia had previously avoided direct attacks on Syrian opposition forces in the south so as to avoid inflaming tensions with their regional and global backers (which include the US and the United Kingdom as well as Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates), aerial support for the regime’s military operations that began in December 2015 has aided the regime considerably. Assad forces have also recently retaken the town of Athman, making the prospect of the regime re-opening the international road that ties Damascus to Amman increasingly likely.

Shifts in international thinking are also having real effects on the ground. Western powers had previously suggested integrating the armed Syrian opposition fighting in the Deraa Governorate into the military and security forces of a future, post-Assad Syria, but appear now to have abandoned these groups to their fate: as if signaling a tacit acceptance of Moscow’s bombing campaign, a previously clandestine joint operations room in Jordan (known as the “Military Operations Command,” or MOC) which allowed these forces to coordinate with the militaries of a number of foreign military advisers,[2] has been shut down. Observers agree that the regime will now attempt to take control of the towns of al-Hirak, followed by Dael and Abtaa. This would mean complete geographic continuity between the two southern governorates of Deraa and Suwaida, and put a large swath of strategic territory under the power of Assad forces.

An Opposition Tailored to Russian Specifications

It would seem Russia’s primary concern at this stage is to undermine the moderate Syrian opposition and in so doing coerce Syrian and international forces into accepting the Kremlin’s terms for a peace agreement. This can be seen in the geographic analysis of Russian bombardment of targets in Syria, which has been concentrated in three specific regions: in the environs of Lattakia; in the northern portion of the Aleppo Governorate; and in the Deraa Governorate. A close examination of the map reveals that these areas are free not only of ISIL forces—the ostensible target of Moscow’s military might—but of any radical jihadi groups whatsoever. Equally, Russia’s military intervention brings to life the “regime-versus-extremism” dichotomy as a matter of fact. This will ultimately allow Russia to crown whichever group it pleases – the Syrian Democratic Forces for example – as the designated, internationally recognized opposition mandated to negotiate with the Assad regime. This is the only plausible explanation for the way in which Russia’s air force recently bombed an outpost in the north of the Aleppo Governorate, a location held by a moderate opposition group that had been fighting ISIL.

If the new status quo is maintained, the PYD will be able to replace moderate forces within the Syrian opposition along the Azaz corridor, giving the Kurdish group the chance to leave Afrin and position itself along the frontline with ISIL on the Turkish border. This will nurture the creation of a de-facto Kurdish self-rule territory on both banks of the Euphrates, and will make it impossible for either the moderate Syrian opposition, Turkish, or Arab militaries to take control of the territory ISIL is being pushed out of.

Conclusion

From the first round of stifled negotiations at Geneva III, it became abundantly apparent that the Assad regime and its backers were waiting for a military victory that would allow them the upper hand at the table. The high price it would pay in casualties, however, makes a complete and outright military triumph for the regime in and around the Aleppo Governorate very unlikely, despite a number of smaller breakthroughs it has enjoyed. Even Russia’s intense firepower has proved to be insufficient to hold the territory evacuated by the moderate Syrian opposition. This suggests that the regime and its allies are likely to focus on a single aspect of recent UNSC resolutions: a complete ceasefire in the Syrian conflict. Only such a ceasefire would allow the Assad regime to consolidate its control over areas it has recently captured, and where the population is resolutely opposed to the regime in Damascus.