On 11 November 2025, Iraqis are heading to the polls to cast their vote in the sixth parliamentary election since the 2003 invasion and subsequent deposition of Saddam Hussein. The last set of elections were held in the wake of, and as a solution to, the

Tishreen uprising that swept the country in the autumn of 2019. Meanwhile the current elections are taking place against the backdrop of regional changes brought about by Israel's aggressive wars against Gaza, Lebanon, and Iran since the Al-Aqsa Flood and the fall of the Assad regime. Iraq’s dominant government and non-government political forces have not agreed on a shared vision or unified stance on these developments, nor on how to respond to them. Rather, these events have deepened polarization within Iraqi politics, as reflected in the ongoing election campaigns.

On 11 November 2025, Iraqis are heading to the polls to cast their vote in the sixth parliamentary election since the 2003 invasion and subsequent deposition of Saddam Hussein. The last set of elections were held in the wake of, and as a solution to, the

Tishreen uprising that swept the country in the autumn of 2019. Meanwhile the current elections are taking place against the backdrop of regional changes brought about by Israel's aggressive wars against Gaza, Lebanon, and Iran since the Al-Aqsa Flood and the fall of the Assad regime. Iraq’s dominant government and non-government political forces have not agreed on a shared vision or unified stance on these developments, nor on how to respond to them. Rather, these events have deepened polarization within Iraqi politics, as reflected in the ongoing election campaigns.

Voter Turnout Expectations

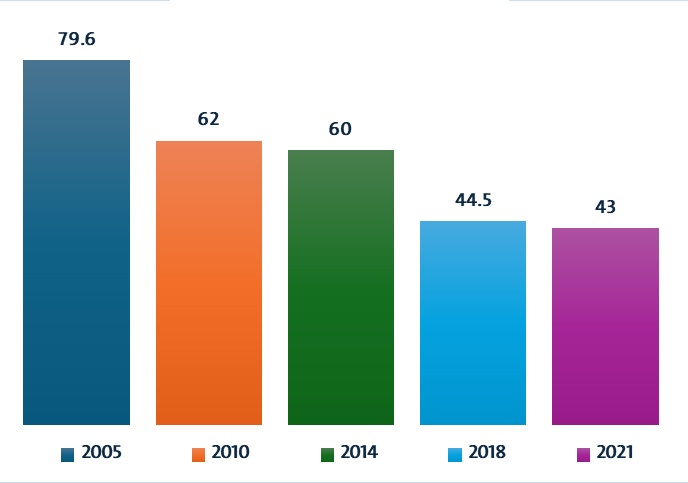

Amid a prevailing sense that the electoral process does not generate any meaningful change in governance or political practice, the turnout is widely expected to be the lowest to date, following a pattern of steady decline in turnout with each successive election. The table below illustrates the declining voter turnout in Iraqi parliamentary elections since the first such elections were held in 2005.

Voter Turnout in Iraq Since 2003[1]

Source: "Voter turnout in Iraq after the 2003 US invasion," Amwaj Media, accessed on 28/10/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPa1

A Return to Pre-Tishreen Electoral Laws

In March 2023, the Iraqi Parliament voted to introduce amendments to the election law, specifically Law No. 9 of 2020. These amendments reverted the electoral system to the format used before the early elections of 2021.[2] Previously, electoral districts were divided into 83 smaller districts, a division that allowed for the rise of new political forces and independent candidates. Parliament then voted to make each governorate a single electoral district and to calculate the electoral quotient using the Sainte-Laguë method with a divisor of 1.7. This system favours larger parties, as seats are distributed proportionally within each district to lists and entities based on the percentage of votes they receive. This reduces the chances of smaller blocs winning seats. The system used in the 2021 elections, considered an achievement of the Tishreen uprising, was based on a single non-transferable vote system, which empowered independents and emerging political forces.

Entrenchment of Sectarian Structures and the Decline of “Cross-Sectarian” Forces

According to figures released by the Independent High Electoral Commission, Tuesday’s elections will include the participation of 31 coalitions, 38 political parties, and 75 independent candidates, all competing for 329 parliamentary seats, nine of which are reserved for minority quotas.[3] With the launch of electoral campaigns on 3 October, a striking paradox (if not outright contradiction) has become apparent: this election cycle has played host to the most overtly sectarian rhetoric in post-2003 Iraqi electoral history. The political contest is no longer one between blocs representing rival sectarian identities, nor between sectarian-based blocs and others seeking to project a broader national platform. Instead, the competition has become largely confined to within each sectarian constituency.

The prevalent discourse surrounding the current elections further consolidate the retreat of detailed political programmes in favour of personalist campaigning centred around the name, image, and persona of each bloc’s leader – often accompanied by a brief, slogan-like phrase that encapsulates the bloc’s supposed message and vision, such as

“State of Law”, “Strong Iraq”, “Reconstruction and Development”, “Progress”, “Sovereignty”, “National Resolution”, or

“The Alternative”. A significant number of these slogans carry an unmistakably sectarian undertone that asserts a sense of privilege or entitlement associated with that sect.

For instance, the

National State Forces Alliance, led by Secretary-General of the

Al-Hikma Movement, Ammar al-Hakim, adopted the slogan

“Don’t Waste It”, an appeal to the Shiʿa public to preserve what the campaign implicitly portrays as the rights and authority of “the largest component” – that is, the Shiʿa community – thus implying that holding power constitutes a form of Shiʿa entitlement not to be relinquished.[4] Similarly, the

Progress Party, led by former Speaker of Parliament Mohammed al-Halbousi, adopted the slogan

“We Are a Nation”, invoking the Sunni community as a distinct “nation” set apart from Iraq’s other groups, which are framed as mere sects or minorities.[5] In this electoral context, “we” refers not to the Iraqi people as a whole, but to each sectarian community in isolation.

As inter-sectarian competition has receded, giving way to intra-sectarian rivalry, the intensification of sectarian discourse functions primarily as a tool for parties within each community to demonstrate their superior claim to represent and defend that sect. One of the salient features of this election – reflecting patterns already visible in previous cycles – is the pronounced fragmentation of sectarian blocs, which have chosen not to enter into coalitions. Consequently, the elections are set to perform the function of determining the relative weight of each bloc

within its own community, rather than constituting a nationwide contest for power.

Within this framework and given that the Shiʿa political elite assert their right – grounded in demographic realities – to hold the office of Prime Minister, the primary function of parliamentary elections has effectively become the quantification of political capital among Shiʿa blocs. The bloc that ultimately nominates the Prime Minister may not necessarily be the one that wins the most seats, but rather the one capable of brokering an intra-Shiʿa deal to form the largest parliamentary grouping. This has, in fact, been the case in two out of Iraq’s five previous parliamentary terms. Such dynamics reveal a deeper crisis of legitimacy within Iraq’s political system. Given widespread voter abstention, declining turnout, and the fact that the ruling bloc typically represents only the Shiʿa component and not necessarily the electoral majority, the resulting government ultimately reflects a narrow segment of the Iraqi populace rather than a truly national mandate.

In this context, the broader regional shifts of the past two years have also left a tangible imprint on Iraq’s electoral environment. Iran’s ability to orchestrate electoral alignments within the Shiʿa camp appears diminished compared to previous years, while US pressure on the Iraqi government to curb the influence of Iran-aligned armed factions has intensified. These factions themselves now face stringent sanctions that may shape both the post-election bargaining landscape and the overall political balance.

Against a backdrop of waning electoral enthusiasm and a lack of genuine political commitment to democratic reform, Iraq’s dominant political forces appear to regard the elections less as a vehicle for change than as a mechanism for consolidating their respective sectarian bases. This is evident in the fragmentation within the

Coordination Framework – an alliance of Shiʿa parties, formed originally in 2021 to counter the rising political power of Muqtada al-Sadr – whose constituent parties chose to contest the elections separately, despite its previous function as a de facto state management council, while declaring their intention to reunite after the vote. A similar pattern is visible among Sunni political forces, which, despite efforts at reconciliation, are currently locked in fierce electoral competition for seats in the predominantly Sunni provinces.

The Map of Political Forces and Electoral Alliances

The configuration of political forces competing in the current Iraqi elections can only be understood with reference to the ethno-sectarian division upon which the post-2003 political order was constructed. This division has become the key to understanding Iraqi politics and is increasingly entrenched over time. Iraq’s political landscape can be broadly divided into three main components: Shiʿa forces, the Sunni forces, and Kurdish forces.

Although there has always been a limited space for so-called civil forces, made up of secular or cross-sectarian movements, within the political process since 2003, such as the Iraqi National Accord (Wifaq) led by former Prime Minister Ayad Allawi, this space has steadily narrowed. While there were moments of expansion, most notably with the Iraqiya List, which won the 2010 elections, or with the Sadrist movement’s call ahead of the 2021 elections to form a cross-sectarian bloc, these initiatives ultimately receded, giving way once more to small, traditional leftist or secular coalitions that typically secure only a handful of seats.

In the landscape of Shiʿa political forces participating in this election, the conspicuous absence of the Sadrist Movement stands out. The Sadrists had won 71 seats in the 2021 elections but subsequently withdrew from the political process after failing to form a governing coalition due to the intransigence of other Shiʿa factions and their refusal to ally with them. For the current election, Al-Sadr has officially declared a boycott.

Among the coalitions participating in the elections, the most prominent is the

Reconstruction and Development Coalition, led by Prime Minister Mohammed Shiaʿ al-Sudani. al-Sudani was nominated for the premiership by the

Coordination Framework, which brings together the major Shiʿa forces – with the exception of the Sadrists – most of which maintain close ties to Iran. Yet, like his predecessors, al-Sudani has established his own political bloc, capitalizing on the political momentum afforded by incumbency and the clientelist nature of Iraq’s political system, which relies heavily on patronage networks. al-Sudani has openly expressed his intention to seek a second term[6] in order to continue the programme he launched at the start of his tenure, known as the “Service Government.”[7] Accordingly, his electoral alliance has expanded to include provincial governors who have demonstrated relative success in local administration – among them, the governors of Basra, Wasit, and Karbala – whose reputations are expected to strengthen his position at both the local and national levels.[8]

Al-Sudani’s principal electoral asset, according to his own narrative, lies in the reconstruction projects undertaken during his premiership – particularly in transport, infrastructure, and housing. Accordingly, the name and campaign message of his alliance,

Reconstruction and Development, draws upon the notion of reconstruction as both a symbol and substance of achievement, with “reconstruction” deliberately placed before “development” to underscore its primacy.

However, key figures within the

Coordination Framework – notably Nouri al-Maliki and his

State of Law Coalition – oppose al-Sudani’s bid for a second term. They accuse him of reneging on those who nominated him for the premiership and of exploiting his position to build an independent political base.[9] Their stance reflects a broader trend among the Shiʿa governing elite to redefine the office of Prime Minister as a primarily executive role, while reserving the authority to determine the government’s general policy direction for the Shiʿa ruling coalition itself. It is therefore likely that this coalition will seek to prevent al-Sudani, or any future prime minister, from renewing his mandate.

Leveraging the advantages of incumbency, al-Sudani has succeeded in attracting a wide spectrum of political forces and personalities to his alliance, including actors from outside the Shiʿa camp. Among the most prominent are: the

National Contract party led by Faleh al-Fayyad, head of the Popular Mobilisation Forces;

Wataniya led by Iyad Allawi; Minister of Labour Ahmed al-Asadi, who leads the

Bilad Sumer Bloc; the

National Solutions Alliance, which includes civil forces associated with the

Tishreen protest movement such as

Nazil Akhud Haqqi (“I Am Coming Down to Claim My Right”); and local alliances at the provincial level, such as

Karbala CreativityAlliance led by Governor Nassif al-Khattabi. Al-Sudani’s bloc is widely expected to come first, potentially winning around sixty seats or more.[10]

The second major force within the Shiʿa political field is al-Maliki’s

State of Law Coalition, through which he seeks to regain the premiership.[11] The significance of this alliance lies in the deep institutional and historical roots of the

Islamic Dawa Party and in the extensive networks of influence and patronage that al-Maliki established during his two terms in office between 2006 and 2014. Another notable Shiʿa coalition, Ammar al-Hakim’s National State Forces Alliance, was hit recently by the withdrawal of the

Victory Alliance, led by former Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi. Al-Abadi justified his departure by protesting what he described as the pervasive influence of “political money” and the absence of effective safeguards to prevent its misuse.[12]

Other prominent Shiʿa actors participating in the elections include:

Al-Sadiqoun Bloc, led by Qais Al-Khazali, Secretary-General of

Asaʾib Ahl al-Haq, which is fronting Higher Education Minister Naeem al-Aboudi as its public face; the

Badr Organisation list, headed by Hadi al-Amiri, Secretary-General of Badr;

Abshir Ya ʿIraq, led by Humam Hamoudi, leader of the Supreme Islamic Iraqi Council;

Asas, headed by First Deputy Speaker of Parliament Muhsin Al-Mandalawi; and the

Tasmim Alliance, led by Basra Governor Asaad al-Eidani, whose campaign, like al-Sudani’s, foregrounds his record of service delivery as the governor of Basra.

The current elections have further underscored the decline of traditional Sunni political forces, particularly those that dominated the Sunni political sphere in the years following 2003, such as the

Iraqi Islamic Party and long-established leaders like Osama al-Nujaifi and Saleh al-Mutlaq. In their place, two major blocs have emerged, now challenged by two rising competitors, led by what might be termed the second generation of the Iraqi Sunni elite.

The two principal forces are:

- The al- Seyada Party, led by businessman and politician Khamis al-Khanjar, who presents his party as the principal representative of Iraq’s Sunni Arabs.[13] The party brings together several smaller groups and figures, including Speaker of Parliament Mahmoud al-Mashhadani and the

LegislationParty headed by Ziad Al-Janabi. It has also formed alliances with locally based parties such as

Al-Masar Al-Watani, led by Abdullah Atheel al-Nujaifi and primarily active in Nineveh Governorate.

- The

Progress Party, led by Mohammed al-Halbousi, whose political discourse has evolved markedly between the 2021 and current elections. Having previously centred his message on reconstruction and governance, al-Halbousi now embraces an overtly sectarian tone, framing his campaign around Sunni identity under the slogan

“Sunni in spirit and identity”.[14]

The two competing forces are:

- The

AzmAlliance, led by MP Muthanna al-Samarrai, which includes a number of Sunni parties and political figures.

- The

National Resolution Alliance (al-Hasm al-Watani), headed by Defence Minister Thabet al-Abbasi. This coalition includes several Sunni parties, among them

The Solution Party and

Nineveh for Its People, led by Abdullah Hamidi Ajil al-Yawar, chief of the Shammar tribe, along with former Nineveh Governor Najim al-Jubouri.

In contrast to the volatility of the Sunni and Shiʿa political arenas, the Kurdish political field remains more stable and institutionally consolidated, continuing to be dominated and effectively divided between the two major parties: the

Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), led by Masoud Barzani, and the

Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), led by Bafel Talabani. Since the death of the PUK’s founder and former Iraqi president, Jalal Talabani, the party has experienced significant internal rifts, marked by power struggles between the party leadership and political bureau on one side, Talabani’s sons – backed by their mother, Hero Ibrahim Ahmad (daughter of Ibrahim Ahmad, Talabani’s political partner in founding the PUK) on another, and their cousins on yet another front.

This enduring bipolar division continues to cement the dominance of the two main Kurdish parties, leaving other Kurdish forces – particularly the Islamic ones, such as the

Kurdistan Islamic Union (affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood) – in a marginal position. Attempts to challenge this duopoly have failed, as seen in the experience of the

Gorran Movement, founded in 2009 by Kurdish politician Nawshirwan Mustafa, Talabani’s former deputy in the PUK, who broke away to establish his own reformist platform. Following his death in 2017, the movement’s influence rapidly declined. The same trajectory appears to be unfolding for the

New Generation Movement, founded and led by businessman Shaswar Abdulwahid, which sought to dismantle the dominance of the two ruling Kurdish parties and expand its parliamentary representation, having won nine seats in the 2021 elections,[15] but which has since faced increasing repression, including the arrest and prosecution of its leader in 2025.

As for civil, cross-sectarian forces, most of which boycotted the 2021 elections in protest at the wave of assassinations and threats targeting their activists, they have returned to the electoral arena through the

Albadil Alliance. This coalition brings together a range of secular and leftist organisations and figures, including the

Iraqi Communist Party, the

Independence Party led by MP Sajad Salim (a prominent figure in the

Tishreen movement),

Al Bayt al-Watani led by activist Hussein al-Ghorabi, and the

National Civil Movement, led by former MP Shirouk Abayachi. The alliance is headed by Adnan al-Zurfi, the 2020 prime ministerial nominee and twice governor of Najaf, whose name is closely associated with

Saulat al-Fursan (Operation Charge of the Knights) – a 2008 campaign conducted under Nouri al-Maliki’s government to drive the Sadrist Mahdi army out of the southern cities. Alongside

AlBadil, other civic alliances have also emerged, such as the

Democratic Civil Alliance, led by academic and politician Ali al-Rufaʿi, which brings together several civil and democratic groups that were part of the

Tishreen protest movement.

Conclusion

Amid expectations of low voter turnout in the current elections, political forces regard the electoral process as an opportunity to consolidate their political weight through their established voter bases. While some actors may not necessarily be genuinely concerned with increasing participation rates, they nevertheless view elections as a mechanism for redistributing power balances within the political process and among the constituent communities themselves. This approach is manifested in their efforts to pursue two parallel strategies of electoral mobilization: the first relies on identity-based, particularly sectarian, rhetoric, while the second draws upon entrenched networks of patronage and influence that ensure electoral loyalty. Consequently, Iraq remains captive to its sectarian and ethnic divisions, inhibiting the emergence of a genuinely national political agenda and turning elections into yet another occasion for reproducing the existing political order.

[1] Doubts persist regarding the accuracy of the figures announced by the Iraqi Electoral Commission, as civil society organizations that monitor the elections argue that the voting percentages are lower than the figure announced, in addition to accusations of deliberate "manipulation," since the commission shows not the percentage of voters among all Iraqis who have the right to vote, but rather from the voters who updated their electoral register (i.e., those who have become eligible to vote, as those who have not updated their electoral register are ineligible).

[2] “Iraqi Parliament Passes Controversial Vote Law Amendments,”

Aljazeera, 27/3/2025, accessed on 28/10/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPiu

[3] "56 out of 349 parties are participating in the Iraqi parliamentary elections," Rudaw, 27/10/2025, accessed on 28/10/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPi3

[4] "Al-Hakim launches the slogan 'Don't Waste It': Had it not been for the awareness of the largest component, Iraq would not have withstood terrorism," Rudaw, 10/10/2025, accessed on 28/10/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPyj

[5] "Al-Halbousi: We were, are, and will remain a nation,"

Al-Sharqiya, 10/18/2025, accessed on 10/28/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPOq

[6] "Man in the News - Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shiʿa’ al-Sudani Seeks Second Term,"

Reuters, 4/11/2025, accessed on 9/11/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPhP

[7] "Prime Minister al-Sudani intends to form a service-oriented government with 22 ministries,"

Middle East Online, 17/10/2022, accessed on 9/11/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BP0p

[8] "Features of a new alliance between al-Sudani and the 'three powerful figures' in Iraq,"

Asharq Al-Awsat, 25/8/2024, accessed on 9/11/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPVj

[9] "Sources for 'Al-Aalem Al-Jadeed': Iran informed the Coordination Framework of its refusal to renew Al-Sudani's term,"

Al-Aalem Al-Jadeed, 5/11/2025, accessed on 9/11/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPnH

[10] "Poll: Sudanese will win 60 seats in the elections,"

Baghdad Today, 5/112025, accessed on 9,/11/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPSe

[11] "State of Law Coalition insists on nominating Maliki for the next Iraqi prime minister,"

Shafaq News, 5/10/2025, accessed on 9/11/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPpZ

[12] Safaa al-Kubaisi, "Al-Abadi's Coalition Questions the Integrity of the Upcoming Parliamentary Elections and Withdraws its Candidates,"

Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, 28/6/2025, accessed on 9/11/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPPQ

[13] According to the party’s profile on its website, al-Seyada is the largest Sunni Arab political party in Iraq, formed following the 2021 Iraqi parliamentary elections and officially founded on 25 January 2022. It claims to represent the main component of Iraqi society with a pan-Arab nationalist spirit and strives for security and stability. See: “About Us,” official al-Seyada Party website, accessed on 9/11/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BOUX

[14] "Sunni in spirit and identity: Al-Halbousi speaks in sectarian terms during an election rally,"

Nabdh, 18/10/2025, accessed 9/11/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BPHi

[15] The New Generation Movement expresses its desire to usurp the position currently held by the two Kurdish parties on its website: "We are working to prevent the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) from representing the citizens of the Kurdistan Region in Baghdad and from manipulating the salaries, livelihoods, lives, and future of the citizens of this region." See: "The New Generation Movement will participate in the next Iraqi government," New Generation Movement website, 27/9/2025, accessed on 9/11/2025, at:

https://acr.ps/1L9BOVd