Definition

Trade wars are a costly tit-for-tat dynamic where one country imposes or increases tariff and non-tariff barriers, prompting retaliatory measures from its trade partners. These trade barriers stem from protectionist policies – the very approach that globalization and modern international trade frameworks have aimed to reduce or eliminate.

Trade wars are a costly tit-for-tat dynamic where one country imposes or increases tariff and non-tariff barriers, prompting retaliatory measures from its trade partners. These trade barriers stem from protectionist policies – the very approach that globalization and modern international trade frameworks have aimed to reduce or eliminate.

Adam Smith, among others, argued that free trade is essential to preventing such conflicts. Although trade wars are not a new phenomenon, their underlying objectives have remained consistent over time: to shield domestic industries and correct trade imbalances.

Major Reasons Behind Recent Trade Wars

Recent trade developments, public officials being more vocal, and trade decisions make trade wars a more visible reality. Yet they originate from latent factors that go back decades.

1. Long-Term Slow Economic Growth

The

Subprime Crisis erupted at the end of 2007 in the United States, triggering an international economic crisis that spread worldwide and primarily affecting the US's major economic trade partners. While the Subprime Crisis itself eventually subsided, a rift in economic performance became apparent, marking the beginning of an era of sluggish economic growth. This led governments to constantly struggle to find ways to generate growth and improve their trade balances.

COVID-19 further exacerbated these challenges. The pandemic led to increased costs of raw materials, as well as associated costs like insurance and transportation. At the same time, to mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic, governments adopted expansionary monetary policies that caused inflation to rise even within the European Union. In this environment, cost-based competition took on an entirely new dynamic.

2. Increasing Competition in the High-Tech Sector, and Fast-Paced Developments in Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Though technology has long been recognized as a component in the production of final goods, perhaps the time has come to distinguish high-tech and AI from traditional sectors of production (whether industries or services). In fact, technology is highly embedded in critical strategic sectors: services, AI, and military projects and weapons.

High-tech goods and services, in particular, require scarce resources – not only those limited in quantities, but which are also localized in very particular regions. Those countries and regions become of interest to competitors, as for instance with Taiwan and the recent political developments in Ukraine and Russia.

3. Changes in the International System

The

emergence of new powerful economic and military players is changing the rules of the game. It intensifies international competition over resources and leads governments to take control of bigger shares of the international market, seeking broader economic and political influence whilst also accumulating greater wealth.

This development has intensified international competition and, hence, brought about a more polarized world: for instance, there is the well-known Chinese “One Belt One Road” Initiative, in competition with another initiative led by the US and India. Despite debates on the feasibility and potential outcomes of “One Belt One Road”, China has made massive worldwide investments mainly in infrastructure in Africa (mining included), Asia, and Europe. As these represent a clear threat to the US, Trump recently declared he will impose restrictions on China’s investments in what he called “strategic sectors” and “infrastructure”[1], amid recurring debates around the Chinese investments in Panama Canal.

This trajectory is a straightforward illustration of a

return of the state, as seen in the Subprime Crisis, the clearly pronounced and policies adopted by Trump during his first term, his decisions to increase tariffs on Chinese imports, government interventions and policies (especially at the monetary level) during COVID-19, and most recently Trump’s policies on trade barriers affecting countries beyond China.

Yet while attention is drawn to tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade, one can easily overlook another strategic element: human capital and knowledge accumulation, which can bring about the dissipation or dissolution of those barriers. Globalization and international free trade brought an expansion of the knowledge worldwide. Investments and imports are also associated with knowledge transfer: importing a laptop, for instance, requires the importer to learn how to use it, and potentially, to copy its technology. Given the nature of the international goods that are subject to competition, non-tariff barriers seeking to protect recent and strategic innovations are not strictly possible at this stage, especially that the basic knowledge required to innovate in strategic sectors is now available in different countries. The best recent example would be the last incident between Deep Seek and NVIDIA.

How Do Trade Wars Translate? A Few Illustrations

- Trump is promoting a policy to bring strategic sectors to the US soil, reducing international economic dependency. Yet an important aspect of human capital is accumulated through contact with imported foreign technology. Monopolizing the production of a technology (or the high geographic concentration thereof) can lead to lower development in other countries but may also motivate other economies to develop parallel technologies.

- China has decided to convert part of its international reserves into gold, which has been a major reason behind the unprecedented peak in the commodity’s price. We may recall that China brought the Euro to USD rate to a peak in 2011 when it decided to invest in European bonds, leading to losses in European exports.

- Relatively recently, China has overtaken the US in international trade. China’s total all-sector direct investments in 152 countries amounted to USD 85.3 billion in June 2024.[2]

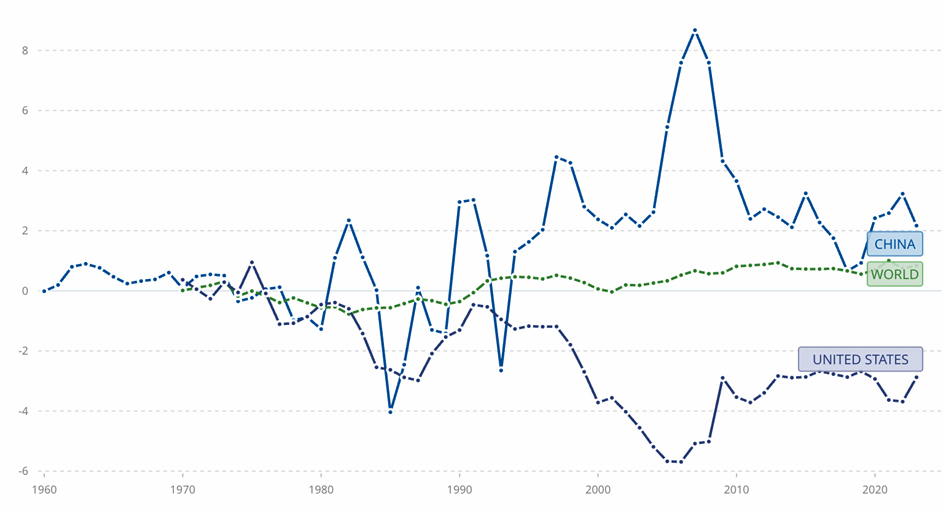

Figure 1: External balance on Goods and Services (% of GDP)

Source 1: World Bank data

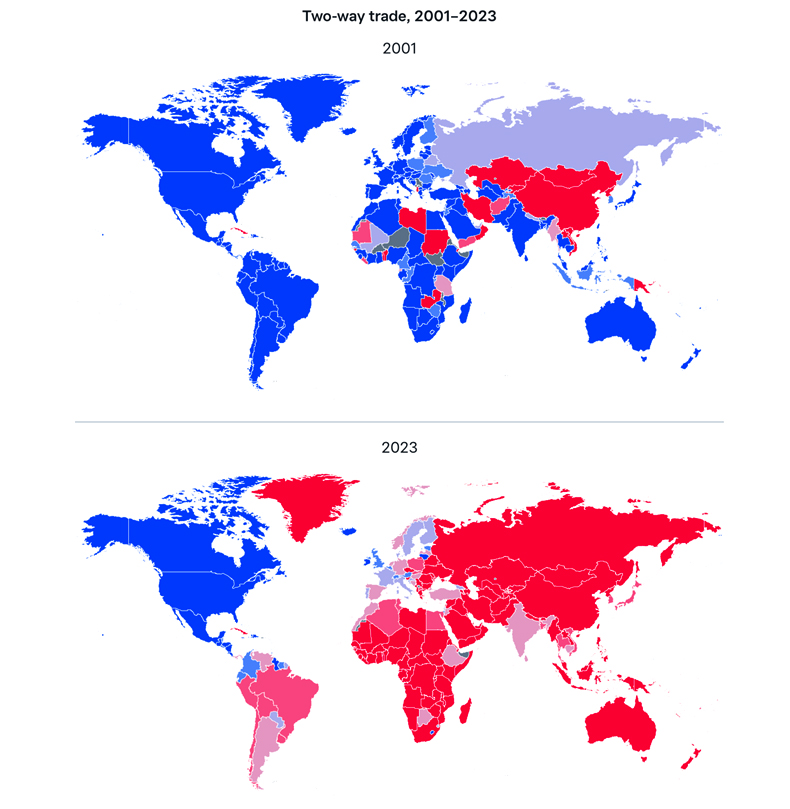

Map 1: Two-way trade interactive map, 2001-2023

Source 2: Rajah and Albayrak (2025), IMF Direction of Trade Statistics database

This dominance is likely to persist, with China’s GDP expected to rise in the coming 20 years.

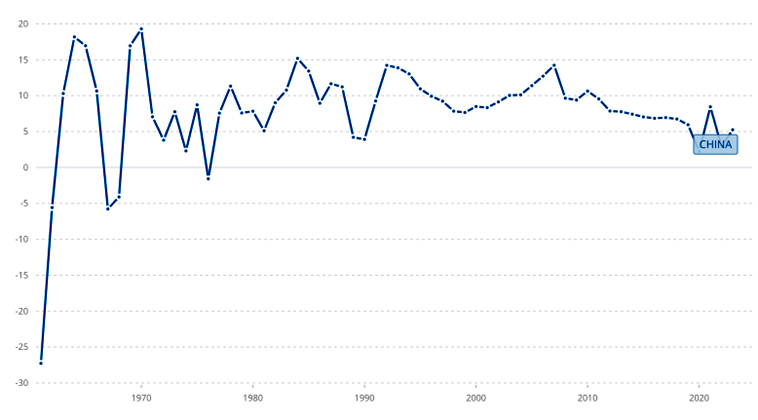

Figure 2: China’s growth rate

Source 3: World Bank data

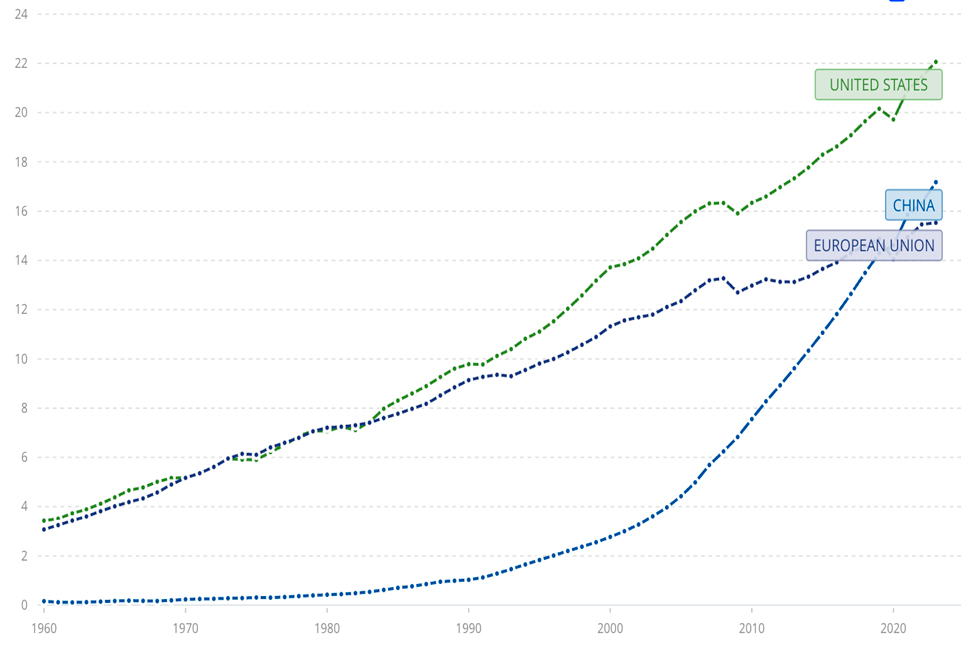

China registered a 5.2% growth rate in 2024. At this pace, China will be able to double its GDP in 13.5 years. A comparison of real GDP between major players shows a decline in the performance of the European Union, but a rapid convergence between China and the US.

Figure 3: Real growth rate

Source 4: The World Banka data

- Given soaring inflation rates since COVID-19, any implementation or increase of tariffs will directly translate into higher prices for final goods and services, purchased by households and end users. On the other hand, imports will become more costly, directly impacting the production and supply-side of the market and, consequently, the competitivity of those imports in local and international markets.

- While all eyes are now on the ping-pong game between the United States and China, a deeper look at the European Union raises many questions.

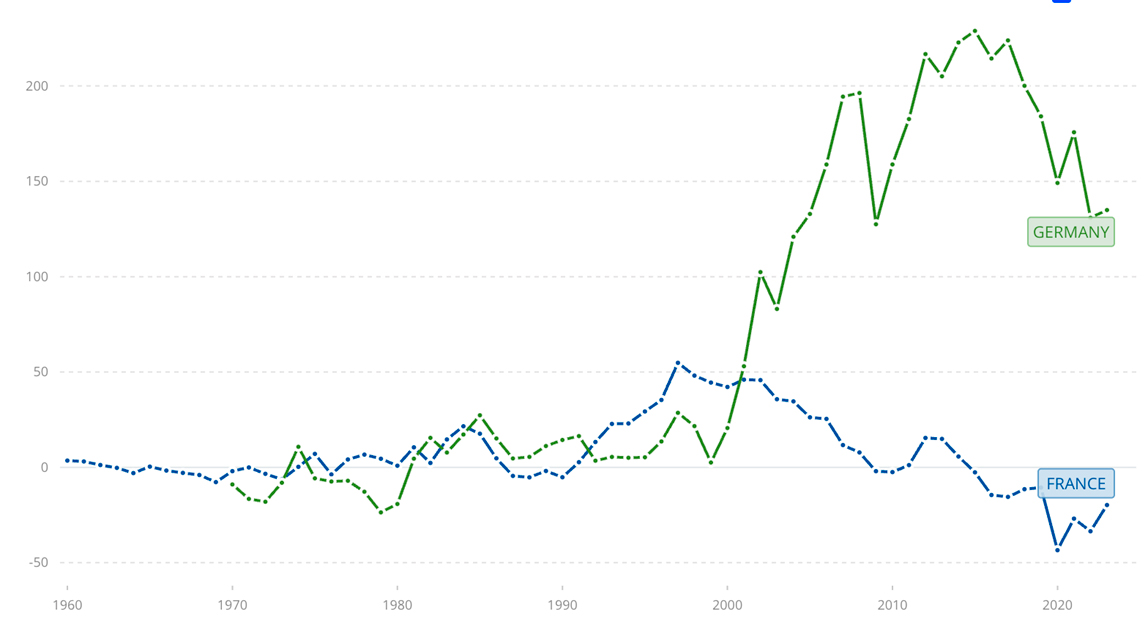

Figure 4: Net Trade Balance (Germany vs France)

Source 5: The World Bank

The above graph shows the net trade balance of Germany and France, each as the first trade partner of the other. A deeper look shows how Germany was able to control its production costs and consequently have higher exports, at the expense of its major trade partner.

- China has engaged in exchange rate manipulation in different instances, keeping the Renminbi artificially low to boost exports, as well as the US particularly after 2008, flooding the market with US dollars and damaging the value of European exports.

Key takeaways

The reshaping of global trade has led to the emergence of new economic players and new categories of goods. Combined with a prolonged period of sluggish economic performance, this shift has contributed to the recent rise in trade wars.

- Trade wars and the resurgence of protectionism are closely linked to the reassertion of state power, particularly in countries that once championed globalization, free trade, and open markets – namely, the United States and parts of Europe.

- These trade conflicts risk exacerbating the economic stagnation that has persisted since the 2007 financial crisis. The negative impacts are not limited to the countries directly involved, as financial contagion can spread to their neighbours and main trading partners. It is worth noting, however, that major players like the US and China continue to record relatively high growth rates.

- Although the European Union was created to boost regional trade and enhance the bloc's economic strength, internal rivalries – especially the ongoing competition between Germany and France – undermine these objectives and are counterproductive for both nations.

- Classical theories of international trade advocate for open markets and caution against protectionist policies, warning that such approaches often trigger retaliatory actions and, eventually, trade wars. Current developments, including tensions involving Canada, China, and Brazil, confirm these theoretical predictions.

- While international trade theory remains relevant in explaining trade flows, incentives, and the benefits of cooperation, the return of state-centric economic strategies and protectionist measures – especially in a climate of weak economic performance – risks pushing economies closer to a prolonged and deeper downturn.

- It is also important to consider that contemporary conflicts increasingly take non-traditional forms, such as cyber-attacks and high-tech warfare involving surveillance technologies, drones, and data systems. The escalating global race for supremacy in high-tech and artificial intelligence (and the resources that fuel them) is tantamount to a modern arms race.

- So far, retaliation in trade disputes has been relatively limited. For example, China is planning moderate tariff increases of 10–15% on select goods. Both China and the US appear to be the least vulnerable to significant economic losses in the current climate.

[1] Trump’s statement on 22/2/2025.

[2] Ministry of Commerce, People’s Republic of China, “Brief Statistics of China’s All-Sector Overseas Direct Investment, January–June 2024”, available at: https://acr.ps/1L9zRYD, accessed on 2/3/2025