Despite the distinctiveness among North African countries of Morocco's electoral experience on November 25, the polls took place under unprecedented circumstances, namely the pressures engendered by the wave of Arab popular protests, some of which evolved into revolutions and led to the fall of regimes were considered allies of Morocco's It should be noted that these legislative elections were held earlier than planned. Amid the atmosphere of instability reigning in several Arab countries, Morocco also witnessed massive demonstrations, beginning in February 2011, calling for radical democratic reforms. These protests seemed to have the same potential as the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, and Morocco's King Mohammad VI reacted to these pressures on March 9 by issuing a quick proposition for constitutional amendments, a move widely seen as attempting to defuse the momentum of the popular movement.

After the approval of the proposed amendments in a referendum on July 1, the early legislative elections were scheduled for November and held accordingly, with the Islamist-leaning Justice and Development Party winning a quarter of the seats. At the same time, the previous majority was not banished from the parliament or from participation in the new cabinet. This result did not change the position of the February 20 movement and its supporters, who rejected the elections for having been held under what they perceived as a "constitution granted by the palace" (i.e. not by the people). This opened the door to questioning the effectiveness of the royal reforms in limiting popular anger, as well as doubts about the possibilities of success for a government led by the Justice and Development Party at a critical stage and with high hopes pinned on its performance.

In terms of international reactions, the United States and the European Union lauded the Moroccan elections. However, local observers and political parties, including both participants and some of those that boycotted the polls, insisted that the process has been marred by several infractions. These critics included the Justice and Development Party, the biggest winner of the elections, which pledged to lodge 18 appeals concerning the results in 20 electoral districts. In reality, I think the results are a positive sign for the future of democracy. Given the power of the Morocco's ruling elite (known as the makhzen[1], the tally might have been much more negative for the Islamist opposition. On the other hand, their access to the seat of power reflects an important shift in the palace's perception of the Islamists.

Political analysts assert that the participation rate announced by the Moroccan Interior Ministry - 45 percent of those registered in electoral lists - was weak given the reforms that had been announced by the king on March 9, and the accompanying media and political support accorded to these changes, in which over 30 political parties took part. Despite the fact that the ministry viewed the participation rate as elevated compared to that in the 2007 elections, which did not exceed 37 percent, this was only partly true, because only 13 million Moroccans were registered out of the 21 million who are eligible to vote -which means that the number of Moroccans registered was 2 million less than in 2007. This fact was viewed by the February 20 movement and its supporters as a response to their call for a boycott of the elections (the Democratic Socialist Vanguard Party, the Unified Socialist Left Party, the Democratic Path Party, the Justice and Charity Group, the Nation Party, the Civilizational Alternative Party, Salafist groupings, civic and rights' organizations).

The results in terms of the balance of power

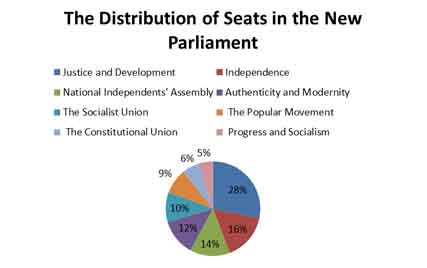

The electoral results confirmed the fact that the Moroccan voter has rewarded everybody in the November 25 vote. In addition to the victory of the opposition Justice and Development Party, the former governmental majority was also able to secure a comfortable number of seats in the parliament, and in the new cabinet as well. To clarify, the bulk of the seats were distributed among the contestants as follows: Justice and Development Party, 107 seats; Independence Party, 60 seats; National Independents' Assembly, 52 seats; Authenticity and Modernity, 47 seats; Socialist Union, 39 seats; Popular Movement, 32 seats; Constitutional Union, 23 seats; Progress and Socialism, 18 seats.

With the exception of the Justice and Development Party all of these parties have previous experience in government. In fact, some of them were categorized among the administrative makhzen parties (i.e. were manufactured by the administration) that were the product of the old conflict between the palace and leftist forces during the 1970s. As for political programs, there are no essential differences between the competing parties, which all raise the slogans of combating corruption, unemployment, and poverty, and promise a state of democracy and human rights.

The Role of the Palace: The Key Player

Despite the fact that Morocco's first legislative elections were held in 1963, when its neighbors endured one-party rule, and the diverse character of the country's political life since that time, the palace has maintained the role of a key, hegemonic player. The palace controls the shape of the political map, as well as the framing and enforcement of the "rules of the game" within discreet limits made known to the other players. The November elections do not represent a genuine exception to the previous context, which led to the shrinking of the power of parties and their influence in public life, including the Justice and Development Party.

Unlike the political traditions in liberal countries, where parties derive their power and influence from their popular bases, the Moroccan experience has been that the power of a party in the political ranks derives from the palace. The more a party's political postures and literature are in tune with the royal will, the more presence it obtains in the institutions of the state, either in an official capacity or by having its leaders and/or other key figures chosen by the king to occupy senior posts in the establishment.

The new Moroccan Constitution defines a political party as follows: "political parties work to organize citizens and contribute to their political formation, increase their engagement in national life and in the running of public affairs, contribute to the expression of the will of the voters, participate in the practice of power on the basis of diversity and alternation, through democratic means, and within the purview of the constitutional institutions[2].

A noteworthy part of this definition is the phrase: "contribute to the expression of the will of the voters and participate in the practice of power". The new constitution does not specify the meaning of partnership between government and the civil society. Does this partnership involve the powers of the king, or does it mean the power sharing with other political parties? It is clear that the political party in Morocco does not "rule" so much as it is considered a mere "partner" in the "practice of power".

In numerous contexts, these factors limit the ability of any Moroccan political party to enact real change in the equation of power, despite the results of the recent elections having brought in a new player from the ranks of the opposition.

Boycotters and Participants

A word is in order regarding the posture of the February 20 movement, and the forces that support it, which are pushing - from outside the establishment - for radical change to the pillars of the equation of power. The movement raises the slogan of "a parliamentary monarchy where sovereignty is for the king and power is for the people", based on a separation of powers and free competition among political forces to represent voters with the objective of reaching the seat of power and enacting a specific program. All this would be guaranteed by laws linking political or administrative responsibility to oversight and accountability.

The fact of the matter is that there has been endless debate over the utility of either boycotting or participating in a political game under rules that still lack democratic credibility. The debate is still ongoing regarding the ability of political powers to affect political decision-making, and whether efforts to do so would be more effective from inside or outside the institutions of rule. Both boycotters and participants always acknowledge the existence of limits that control the competition over power, but the former rejects them while the latter accepts them. These limits (the aforementioned "rules of the game") are created by the king in his two capacities: religious (as the "Commander of the Faithful") and political (as head of state).

Morocco's makhzen is endowed with a massive containment capacity, a power that has permitted the monarchy to survive difficult stages. In this regard, observers recall the experience of "consociational alternation", which introduced the opposition - led by popular leftist figure Abdul Rahman al-Yusufi - into cabinet in 1997. At the time, Morocco was threatened by what late King Hassan II described as a "heart attack"; the palace needed a bridge to guarantee the transition of power to Mohammad VI, which indeed took place, and the experiment ended in 2002 with the return of the technocrats and the leftist opposition avowing its failure and that what took place was not a process of democratic alternation.

However, the pressures of the ongoing Arab Spring, which are impacting several countries where no political reforms or democratic changes took place, is a far more threatening situation for a traditional autocratic regime than the circumstances that forced the Moroccan king to include his leftist opponents. Once more, the royal establishment has shown flexibility and speed in reacting to the situation. It grudgingly accepted the victory of the Justice and Development Party and its heading of the new government after having spent 14 years in the ranks of the parliamentary opposition - which included repeated attempts to prove the party's capacity to bear the burden responsibility and its deserving of the king's confidence, which made the party avoid the practices of a political opposition that might have embarrassed the palace.

The Difficult Balances

The fact is that any opposition party changes once it assumes governmental responsibilities. As a general rule, opposition parties become more moderate in their rhetoric once in power, which is due to their need to defend their programs, positions and interests. Nevertheless, the nature of political life in Morocco (which, as previously explained, is marked by limits set by the king) may open the door for a continuation of the opposition discourse, even from within the halls of power. Government officials will attempt to gain additional positions and powers, while the palace will continue its attempts to keep them in their place so that they do not reach the scale of popularity that would allow them to demand further reforms. This raises a concernabout the future of the conflict between the royal establishment and a government led by the Justice and Development Party.

However, achieving a balance of power with the king's authority is seen by many observers as an extremely difficult challenge. In a span of less than two weeks, for instance, the king appointed several new figures as advisors to the Royal Court, the last of whom was Fuad Ali al-Himma, the most controversial figure on the Moroccan political scene[3].

Some view these appointments, which preceded the announcement of the formation of Justice and Development Party leader Abdelilah Benkirane's cabinet, as the equivalent of a shadow government that operates at the behest of the king - given the powers and authorities that royal advisors have enjoyed in previous governments. This indicates the pivotal role that will be played by Fuad Ali al-Himma in the face of the Justice and Development cabinet. The man is known for his fierce opposition to the Islamists and their social project, and had repeatedly warned against the threat that the Justice and Development Party constituted toward what he describes as "the modernist democratic project in Morocco".

Strategically speaking, and on the domestic level, the November 25 elections represented for the palace an opportunity to reshuffle its cards, and perhaps overcome the most critical stage in the face of mounting popular protests, with the Justice and Development government expected to contain some of the growing popular anger. On the international level, the Moroccan regime could present itself as a "democratic model" capable of transferring power to the Islamists without revolution or victims, which goes in tandem with Western recommendations to Arab governments for years: the necessity of allowing moderate Sunni Islamists to practice rule.

The royal establishment's ability to survive the current stage remains conditional on convincing the popular movement to halt protests and demonstrations in public spaces and allow sufficient time to gauge the performance of the Justice and Development cabinet.

Opposition forces that demand radical reforms remain the difficult player in the Moroccan equation. On the one hand, if these forces cannot achieve effective popular mobilization with which to challenge the authority and its traditional alliances with the makhzen, they will not reach their desired outcome. If these forces struck deals with the government, they would become part of the "game". On the other hand, the palace will not be able to include these forces in a national project that provides a suitable atmosphere for the functioning of a new government without concessions from both sides.

As for the Justice and Development Party, challenged and harassed by the popular movement, it feels the need to play the role of mediator between the February 20 movement and the palace, which may induce it into a struggle with the latter without necessarily guaranteeing it the confidence of the street. At any rate, the makhzen would stand to gain if an Islamist-Islamist clash took place between Justice and Development and the Justice and Charity Movement, which is a major component of the February 20 grouping.

The Test of Justice and Development

Throughout the past 30 years, leaders of Justice and Development (including under its previous names) have sent numerous messages to the ruling establishment expressing their readiness to function in a manner that does not contravene the royal will. Thus, some observers perceive the Justice and Development Party as a modern expression of the Makhzenite religious factions that fulfill the role of defenders of the institution of the Commander of the Faithful. On the ideological level, this party does not pose a threat to the liberal values upon which the political culture of the Moroccan regime and its major leanings are based. Furthermore, the party has sent continual messages reassuring all sides regarding women's participation, tourism, and the sale of alcohol. On the international level, the positions of the Justice and Development Party will not have a major effect since foreign policy decision-making is a royal prerogative without the participation of government political forces, except in the phase of execution.

The Justice and Development Party will undergo its first governmental experience with itself in the driver's seat, an extremely difficult task. This party, with its Islamic pillars, is forced to ally itself with competing left- and right-wing parties with which it has no ideological affinities or previous political alliances. The party had led a long ideological feud with the Progress and Socialism Party, while the Independence Party represents a major competitor given its conservative background and historical role. As for the Popular Movement, its influence among farmers and notables also makes it a considerable competitor.

However, the biggest challenges that the new cabinet will face are the economic and social conditions in Morocco.

The United Nations' 2011 Human Development Report dropped Morocco 16 spots, ranking it 130th among 187 countries, and 15th out of 20 Arab countries. The report shows that theintensity of deprivation in Morocco has reached 45 percent, while 12.3 percent of the population is exposed to the threat of poverty, and 3.3 percent live severe poverty. In addition, the national economy has suffered several setbacks in recent years, including losses at three major public companies: Autoroutes du Maroc (the national expressway operator), Royal Air Maroc (the national airline), and the National Electricity Office. In this regard, we could also list the persistent pressures of specific demands in all the production and service sectors, as well as the hundreds of thousands of unemployed youth awaiting work, including some with post-secondary degrees.

Regarding the party's electoral promises, Moroccan economist Idris Bin Ali sees that "what the Justice and Development Party proposes is to increase the rate of growth to 7 percent and lower the budget deficit to 3 percent, while lowering unemployment. Achieving these targets in the two coming years appears difficult, even unachievable ... According to the International Monetary Fund, in the best of cases, Morocco will witness a growth rate of 4 to 4.5 percent". The economist added that "Europe, Morocco's primary economic partner, is entering a deep crisis, and Morocco's three major sources of growth in recent years have been emigrant remittances and the revenues from tourism and foreign direct investment; there will surely be a decline in these domains."

Among the party's chief electoral slogans was its assertion that it would combat corruption, a task at which its predecessors failed, in the climate of administrative, economic, and political realities that lack the mechanisms for oversight, accountability, and enforcement, and requires strong legal support, and stronger political support, to fight poverty in an effective manner.

The Justice and Development Party will undergo a crucial test when faced with the interference of the king's advisors in governmental responsibilities, in addition to the challenge of influencing decision-making. According to the letter of the Moroccan Constitution, the keys to governance remain in the hands of the king, for he is the Commander of the Faithful and the head of the cabinet, and chairs various councils and committees. He approves the appointment of ministers and of many senior figures in the security forces and civil institutions. He approves the laws emanating from the parliament, and is flanked by a host of bodies that parallel the functions and tasks of the government. Additionally, the king controls vital ministries that are still not occupied by politicians: Interior, Foreign Affairs, Islamic Endowments and Affairs, and the General Secretariat of the Government. After the recent constitutional amendments, and taking into consideration King Mohammad VI's stated intentions to reform, it might be assumed that some of these powers will be transferred to the relevant government departments, with the aim of avoiding bureaucratic overlaps and contradictions and because the king is aware that without delegation of power, both parties (the government and the monarch) will be incapable of effective performance in the difficult conditions which Morocco faces. However, this possibility remains unconfirmed.

Findings and Conclusions

The Moroccan Justice and Development Party's ascent to power differs from those of other "moderate Sunni Islamist" parties in essential ways. For instance, the ascension of the Turkish Justice and Development Party was associated with a deep democratic transformation in which the army conceded its powers due to the necessities of a particular stage of history, and under the pressures of strong conditions for Turkey's prospects for joining the European Union. It may be possible to compare the role of the army in Turkey with that of the makhzen in Morocco in one regard: a shared ability to interfere in political life and to regulate the limits of the political game. Aside from that, they stand in diametrical opposition to each other. In Morocco, the makhzen - in addition to its central political role - plays the role of the guardian of traditional religious values, especially through the assertion of the authority of "the Commander of the Faithful". In Turkey, on the other hand, the army has so far played the role of the sentinel of secular values. We should also not forget the socioeconomic power controlled by the Turkish Justice and Development Party inside Turkey, which put it in command of vital keys in any competition over posts of power and authority, which does not apply to the case of its Moroccan counterpart.

If we look at the Arab neighborhood, we find that parties which were banned until recently are now leading post-revolution political scenes and allying themselves with secular parties to form governments. In Tunisia, the Nahda Party gained an important proportion of the vote, which allowed it to lead the government and control a relatively large share in the Constituent Assembly from which the second Tunisian Constitution is supposed emerge. In Egypt, the latest elections have resulted in a grand victory for the Islamists, strongly increasing their influence. The Moroccan Islamists' arrival in power did not come due to revolution, but as a result of a host of complex factors, including the pressures of the Arab Spring, Western pressures, domestic pressures caused by the political impasse in the absence of reform and democratic change, a the royal response to the popular demands and a royal will to reform, in addition to the absence of significant political forces from the scene of electoral competition.

Scenarios

Today, Morocco faces two possibilities.

In any case, there is no magic solution for problems that have been accumulating for years.

- A third, but still remote, scenario is that the royal establishment will open itself to the demands of those who want the king to be above the game of power and the opposition, allowing him not to risk putting the system in crisis when social conditions worsen, and to content himself with giving directions to those chosen by the people. In the long run, this is the best possible solution as it would guarantee the stability of the monarchy while also subjecting all of the country's politicians to accountability, which satisfies the people. But such an eventuality is not likely to crystallize in the near future.

-----------------------------------

- [1] The name makhzen is given to the ruling elites and networks of power surrounding the king.

- [2] Moroccan Constitution 2011, section one, chapter 7.

- [3] Weeks earlier, both Abdul Latif al-Manuni and Mustafa al-Sahil were appointed, the former being an ex-interior minister and classified among the "hawks" of the Interior Ministry.